Strategies for Inclusive Care to LGBTQIAP+ People with Cancer

Estratégias para uma Assistência Inclusiva a Pessoas LGBTQIAP+ com Câncer

Estrategias para una Atención Inclusiva a las Personas LGBTQIAP+ con Cáncer

doi: https://doi.org/10.32635/2176-9745.RBC.2023v69n2.3671

Ricardo Souza Evangelista Sant'Ana1

1Universidade de São Paulo, Escola de Enfermagem de Ribeirão Preto (EERP-USP). São Paulo (SP), Brazil. E-mail: ricardo.sesantana@usp.br. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3762-4362

Corresponding author: Ricardo Souza Evangelista Sant’Ana, Quadra 8 SIG Primeira Avenida, 2396. Brasília (DF), Brazil. CEP 70610-480. E-mail: ricardo.sesantana@usp.br

INTRODUCTION

Human sexuality encompasses pleasure, reproduction, friendship, love, affection, sexual practices, sexual orientation, and gender. It involves pleasurable tactile sensations, receiving affectivity and loving welcoming from marital, fraternal, or friendly relationships. How sexuality manifests itself is associated with different historical, sociocultural, family, and subjective contexts1-4.

In Brazil, 0.69% of the population of reproductive age identifies as transgender and 1.19% as non-binary. It is clear that a welcoming attitude is the first step to dismantle the obstacles usually found to treat this population; nevertheless, the literature is poor in specific and validated instruments to smooth the approach to LGBTQIAP+ patients with cancer. The acronym LGBTQIAP+ stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, Intersex, Asexual, and Pansexual. The symbol "+" represents all other identities and experiences that are not specifically represented in the acronym5,6.

Unskilled and often prejudiced health professionals typically unaware of the characteristics of this population can significantly impact the access to early diagnosis, delay the treatment and influence the follow up because of incomplete sociodemographic data about gender identity and sexual orientation.

It is necessary that the oncology team develops and provides humanized and qualified care to this community. Health professional training, which in most cases is based on heteronormative populations, can be a contributing factor for prejudice due to inadequate understanding about sexual diversity in the systematization process of inclusive care.

DEVELOPMENT

Implications for clinical practice

Trans people are those who identify with a gender other than what was assigned at birth. Non-binary people are those who do not identify exclusively with the male or female gender. They may identify as agender, bigender, trigender, or as a gender identity outside of the male-female binary. Gender identity is different from sexual orientation, and there are important distinctions between people who identify as trans or non-binary and the LGBTQIAP+ community. The literature about cancer in trans and nonbinary people is limited. However, studies suggest that this population face significant barriers to access the health care system in addition to poor quality of the service offered permeated by stigma and discrimination, culturally ill-prepared personnel, lack of insurance coverage and health policies7.

The studies have shown that patients who identify as transgender or non-binary compared to cisgender patients are more likely to be diagnosed with advanced breast cancer, lower rates of breast-conserving surgery and higher rates of bilateral mastectomy. In addition, trans and nonbinary patients fail to receive adjuvant radiation therapy after breast cancer surgery; in furthermore, when diagnosed with colorectal cancer, it is common to be at a more advanced stage and are less likely to receive the prescribed treatments.

However, researches suggest that LGBTQIAP+ people may face disparities in access to and quality of health care, as well as elevated risks of certain types of cancer8-10.

LGBTQIAP+ people have a higher risk of certain types of cancer, including breast, cervical, ovarian, uterine, anal, and prostate cancers7.

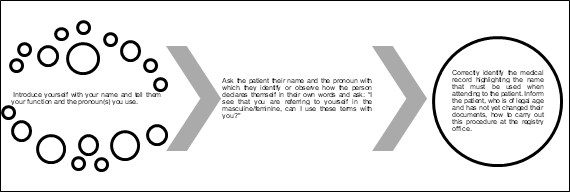

Making the moment of consultation a more inclusive space goes beyond issues related to setting. The recognition, permission and validation of identities and sexual practices, as well as the use of a less binary and sexist language are actions that can mitigate the neglect this population suffers in order to promote health. A model of how to start this approach taken from the Epidemiological Bulletin of the State of São Paulo published in 202211 is presented in Figure 1.

|

|

|

Figure 1. How to start caring for LGBTQIAP+ patients with cancer |

Inclusive language can be helpful to understand family relationships and different support systems and communicate this understanding to the patient. Rather than asking "is this your mother?”, it is less presumptuous to ask "who's here with you today?". Carr12 noted that 70% of LGBTQIAP+ survey respondents reported that their support systems were friends rather than a partner or family member, and this is often referred to as a chosen family. The practitioner can facilitate safe and inclusive interactions by understanding the diversity of support systems in the LGBTQIAP+ community and using inclusive terminology13,14.

There are certain challenges that need to be overcome by health professionals, as well as by public and private health institutions. Teaching and clinical trials dedicated institutions can collaborate to generate robust data to support clinical practice.

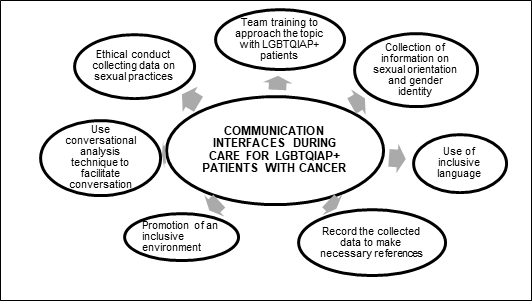

For an inclusive and individualized oncology assistance to LGBTQIAP+ patients with cancer, the following actions must be implemented (Figure 2):

|

|

|

Figure 2. Strategies for inclusive care in oncology |

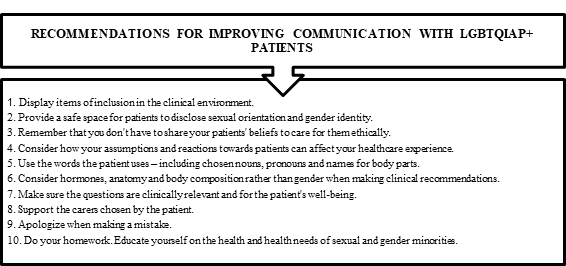

Communication is a key tool in health practices and many investigators attempt to analyze communication interfaces, but adjustments are essential to communicate with LGBTQIAP+ patients with cancer to make them feel welcomed and receive patient-centered assistance. Pratt-Chapman14, in “Considerations on cancer care for patients of sexual and gender minorities”, listed ten recommendations to improve communication with LGBTQIAP+ patients (Figure 3).

|

|

|

Figure 3. Recommendations for improving communication with LGBTQIAP+ patients with cancer |

Barriers to access and risk factors for cancer

The LGBTQIAP+ population presents high rate of use of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drugs. The use of psychoactive substances taken together during sex significantly increases exposure to sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as having condomless sex, changing sexual partners during group sex, dryness, dehydration, and loss of sensitivity, increasing the chances of tissue damage and bleeding15. In addition, obesity has higher rates among lesbian women. All these findings can be considered as risk factors for the increase of chronic diseases, including cancer16.

Populations of Sexual and Gender Diversity (SDG) face innumerous barriers daily in the prevention, screening, acceptance of treatment and future care due to inequalities in access to health networks. Poor training and technical-scientific preparation of health professionals, as well as insufficient scientific funding, development of protocols and policies aimed at this group exacerbate this reality and the lack of specific assistance for these populations16.

The approach to issues related to reproductive health in gynecological consultations is based on cisheteronormative concepts and conduct. These factors favor the presence of worse physical and mental health indicators when compared to the population of heterosexual women. There is no data in the literature that demonstrate a high volume of diagnoses of cancer in trans population in comparison to general population. However, the invisibility of conditions associated with sexual diversity in databases of national and international oncological conditions makes this type of analysis very difficult11,12.

CONCLUSION

Oncology professionals face similar challenges of other health professionals while caring for LGBTQIAP+ patients. It is important to note, however, that caring to cancer patients requires a holistic approach, considering the patient's individual needs, including sexual orientation and gender identity.

To ensure quality care for LGBTQIAP+ patients, it is critical that health professionals receive training and guidance on the specific needs of this population, including understanding the barriers that can thwart access to health care and developing strategies to overcome these barriers.

Although there are no specific studies about the perception that oncology professionals have on LGBTQIAP+ patients, it is important to highlight the importance of training and awareness of health professionals to ensure adequate and respectful care.

CONTRIBUTION

Ricardo Souza Evangelista Sant'Ana participated of all the stages of the article and approved the final version to be published.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

There is no conflict of interest to declare.

FUNDING SOURCES

None.

REFERENCES

1. Griggs KM, Waddill CB, Bice A, et al. Care during pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum, and human milk feeding for individuals who identify as LGBTQ. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2021;46(1):43-53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/NMC.0000000000000675

2. World Health Organization [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; c2023. Sexual health; [cited 2023 Apr 5]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/sexual-health#tab=tab_2

3. Sant’Ana RSE, Zerbinati JP, Faria ME, et al. The sexual and emotional life experiences reported by Brazilian men with head and neck cancer at a public university hospital: a qualitative study. Sex Disabil. 2022;40:539-54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-022-09732-4

4. Shetty G, Sanchez JA, Lancaster JM, et al. Oncology healthcare providers' knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors regarding LGBT health. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(10):1676-84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.05.004

5. Spizzirri G, Eufrásio R, Lima MCP, et al. Proportion of people identified as transgender and non-binary gender in Brazil. Sci Rep. 2021;11:2240. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81411-4

6. Almont T, Farsi F, Krakowski I, et al. Sexual health in cancer: the results of a survey exploring practices, attitudes, knowledge, communication, and professional interactions in oncology healthcare providers. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(3):887-94. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4376-x

7. Ussher JM, Power R, Allison K, et al. Reinforcing or disrupting gender affirmation: the impact of cancer on transgender embodiment and identity. Arch Sex Behav. 2023;52(3):901-20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02530-9

8. Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, et al. Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning populations (LGBTQ). CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(5):384-400. doi: https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21288

9. Tamargo CL, Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, et al. Cancer and the LGBTQ population: quantitative and qualitative results from an oncology providers' survey on knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors. J Clin Med. 2017;6(10):93. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm6100093

10. Bento B. Sexualidade e experiências trans: do hospital à alcova. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2012;17(10):2655-64. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232012001000015

11. Okano SHP. Cuidados integrais à população trans: o que cabe ao atendimento na atenção primária à saúde (APS)? Bepa [Internet]. 2022 [acesso 2023 abr 5];19:1-40. Disponível em: https://periodicos.saude.sp.gov.br/BEPA182/article/view/37729

12. Carr E. The personal experience of LGBT patients with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2018;34(1):72-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2017.12.004

13. Rice D. LGBTQ: the communities within a community. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2019;23(6):668-71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1188/19.CJON.668-671

14. Pratt-Chapman ML, Potter J. Cancer care considerations for sexual and gender minority patients. Oncol Issues. 2019;34(6):26-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463356.2019.1667673

15. Maxwell S, Shahmanesh M, Gafos M. Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;63:74-89. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.11.014

16. Pratt-Chapman ML, Alpert AB, Castillo DA. Health outcomes of sexual and gender minorities after cancer: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):183. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01707-4

Recebido em 30/1/2023

Aprovado em 12/4/2023

Associate-Editor: Mario Jorge Sobreira da Silva. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org//0000-0002-0477-8595

Scientific-Editor: Anke Bergmann. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1972-8777

![]()

Este é um artigo publicado em acesso aberto (Open Access) sob a licença Creative Commons Attribution, que permite uso, distribuição e reprodução em qualquer meio, sem restrições, desde que o trabalho original seja corretamente citado.

©2019 Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia | Instituto Nacional de Câncer | Ministério da Saúde