Impact of Telemedicine for Lung Cancer Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Interrupted Time Series Analysis

Impacto da Telemedicina no Cuidado para o Câncer de Pulmão durante a Pandemia de Covid-19: Análise de Series Temporais Interrompidas

Impacto de la Telemedicina en el Cuidado del Cáncer de Pulmón durante la Pandemia de COVID-19: Análisis de Series de Tiempo Interrumpidas

https://doi.org/10.32635/2176-9745.RBC.2025v71n2.4872

Isabel Cristina Martins Emmerick1; Feiran Lou2; Mark Maxfield3; Karl Uy4

1-4UMass Memorial Healthcare/UMass Chan Medical School, Division of Thoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery. Worcester – Massachusetts – USA.

1E-mail: isabel.emmerick@umassmed.edu. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0383-2465

2E-mail: feiran.lou@umassmemorial.org. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4965-4094

3E-mail: mark.maxfield@umassmemorial.org. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1559-5935

4E-mail: karl.uy@umassmemorial.org. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5790-1342

Corresponding author: Isabel Emmerick. UMass Memorial Healthcare/UMass Chan Medical School, Division of Thoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery. 67 Belmont Street #201. Worcester, Massachusetts, USA. E-mail: isabel.emmerick@umassmed.edu

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic greatly challenged the health systems and cancer care. Objective: To estimate the impact of telemedicine on outpatient visits (OPV) to reduce disease exposure for patients and healthcare providers and minimize the effect on cancer care continuum during the COVID-19 pandemic. Method: Longitudinal quasi-experimental time series using the institutional electronic medical records from January 2018 to December 2021, considering the implementation of telemedicine services in the first and second waves of COVID-19 in March and November 2020, respectively. The primary outcomes were a mean (A) monthly-overall-OPV, (B) monthly-in-person-OPV, (C) monthly-overall-cancer-OPV, and (D) monthly-in-person-cancer-OPV. Results: A total of 5,918 OPV were analyzed. 55.3% of the visits were for females, 87% were White, and the mean age was 66 years. Telemedicine accounted for 25.8% of the visits and 27.7% were cancer-related. White, Black, and Asian patients had a similar percentage of use of telemedicine (26.3%, 25.0%, and 26.8%), while Latinos were less likely to use telemedicine (18%, p=0.018). For outcomes (A) and (C), including telemedicine, the COVID-19 surges did not significantly impact the mean OPV. When telemedicine was not used, there was a statistically significant decline in overall in-person OPV (B) and cancer (D). In the first COVID-19 surge, telemedicine prevented a decrease in monthly-overall-OPV of 59.1% (p=0.001) and 40.9% (p=0.019) for cancer. In the second surge, these values were 64.4% (p=0.001) for monthly-overall-OPV and 59.8% for cancer (p=0.001). Conclusion: The use of telemedicine positively impacted the care for cancer patients in a thoracic surgery service.

Key words: Lung Neoplasms/epidemiology; COVID-19; Health Services; Telemedicine; Remote Consultation.

RESUMO

Introdução: A pandemia da covid-19 foi um grande desafio para os sistemas de saúde e para a assistência ao câncer. Objetivo: Estimar o impacto da utilização da telemedicina para consultas ambulatoriais (CA) para reduzir a exposição à doença de pacientes e profissionais e minimizar o efeito no continuum de cuidados oncológicos durante a pandemia de covid-19. Método: Série temporal interrompida usando prontuários médicos de janeiro de 2018 a dezembro de 2021, considerando a implementação de serviços de telessaúde na primeira e segunda ondas de covid-19 em março e novembro de 2020. Os desfechos primários foram uma média de (A) CA-geral-mensal; (B) CA-presencial-mensal, (C) CA-geral-mensal-câncer e (D) CA-presencial-mensal-câncer. Resultados: Analisaram-se 5.918 CA, 55,3% eram mulheres, 87% eram da raça branca e idade média de 66 anos; a telessaúde representou 25,8% do total de consultas e 27,7% das consultas foram relacionadas a câncer. Pacientes brancos, negros e asiáticos tiveram uma porcentagem semelhante de uso de telessaúde (26,3%, 25,0% e 26,8%, respectivamente), enquanto latinos apresentaram menor probabilidade (18%, p=0,018). Para os desfechos (A) e (C), incluindo a telessaúde, os surtos de covid-19 não impactaram significativamente as CA. Quando a telessaúde não foi utilizada, houve um declínio significativo na CA geral (B) e para câncer (D). No primeiro surto de covid-19, a telessaúde evitou redução de CA de 59,1% (p=0,001) em geral e 40,9% (p=0,019) para câncer. No segundo surto, de 64,4% (p=0,001) para CA geral e 59,8% para câncer (p=0,001). Conclusão: A telessaúde impactou positivamente o cuidado oncológico no serviço de cirurgia torácica.

Palavras-chave: Neoplasias Pulmonares/epidemiologia; COVID-19; Serviços de Saúde; Telemedicina; Consulta Remota.

RESUMEN

Introducción: La pandemia de COVID-19 presentó un gran desafío para los sistemas de salud y la atención del cáncer. Objetivo: Estimar el impacto de la telesalud para consultas ambulatorias para reducir la exposición a la enfermedad para pacientes y profesionales y minimizar el efecto en la continuidad de cuidados oncológicos durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Método: Serie de tiempo interrumpida utilizando registros médicos desde enero de 2018 hasta diciembre de 2021, considerando la implementación de servicios de telesalud en la primera y segunda ola de COVID-19 en marzo y noviembre de 2020. Los resultados primarios fueron una media de las consultas ambulatorias (CA) de (A) CA-general-mensual; (B) CA-presencial-mensual, (C) CA-general-mensual-para-el-cáncer y (D) CA-presencial-mensual-para-el-cáncer. Resultados: 5918 CA fueron analizadas; el 55,3% era de mujeres, el 87% de la raza blanca y la edad promedio era de 66 años; el 25,8% del total de consultas y el 27,7% de las consultas por cáncer fueron de telesalud. Los pacientes blancos, negros y asiáticos tuvieron un porcentaje similar de uso de telesalud (26,3%, 25,0% y 26,8%), mientras que los latinos tenían menos probabilidades de utilizar telesalud (18%, p=0,018). Para los resultados (A) y (C), incluida la telesalud, los brotes de COVID-19 no tuvieron un impacto significativo en las CA. Cuando no se utilizó la telesalud, hubo una disminución significativa en las CA general (B) y para el cáncer (D) en general. En el primer brote de COVID-19, la telesalud evitó una reducción de la CA-general-mensual del 59,1% (p=0,001) y del 40,9% (p=0,019) para el cáncer. En el segundo brote, del 64,4% (p=0,001) para CA-general-mensual y del 59,8% para cáncer (p=0,001). Conclusión: La telesalud impactó positivamente en la atención oncológica en el servicio de cirugía torácica.

Palabras clave: Neoplasias Pulmonares/epidemiología; COVID-19; Servicios de Salud; Telemedicina; Consulta Remota.

INTRODUCTION

In December 2019, the first official case of pneumonia with unknown cause was registered at the World Health Organization (WHO) office in Wuhan, Hubei province in China. The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) that characterized this viral infection grew exponentially, gained the name COVID-19, and was ultimately declared a pandemic in early March 2020. COVID-19 is a type of coronavirus, specifically represented by SARS-Cov2. Acute bilateral interstitial pneumonia characterizes its illness. Although similar etiologic agents have caused other epidemics, as SARS-Cov1 and MERS, SARS-Cov2 presented an unusually rapid and widespread of new cases1-3.

The transmissibility indicator (R0) of the SARS-Cov2 virus ranged from 1.95 (95% CI 1.4-2.5)1 to 6.5 (95% CI 5.7-7.2)4, mean R0 of 3.3 and median of 2.81,4. An R0 value >1 indicates a progressing worsening contagion, where each individual infected will infect >1 other person. Conversely, an R0 value <1 indicates a slowing contagion.

Of the patients infected with the novel coronavirus, 80% will be asymptomatic or have mild disease symptoms. It is estimated that 20% will develop the most severe form of the disease, requiring intensive care and respiratory support, including endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation1. The average recovery period is 20 days, but severe cases requiring intensive care can last from three to six weeks1. As an entire population was susceptible, a very rapid increase in the number of infected people would cause an overwhelming number of severe cases, leading to shortages of hospital beds and high use of limited hospital resources5,6. Risk factors for severe disease include advanced age (> 60 years) and the presence of comorbidities, specifically cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes mellitus, systemic arterial hypertension, asthma, and emphysema4.

As of May 18th, 2020, in the United States and in the state of Massachusetts, there were 1,480,349 million and 86,010 confirmed cases of COVID-19, respectively7,8. At Memorial Health Care on May 16th of 2020, there were 155 positive inpatients (including 56 ICU patients) and 196 cumulative positive employees, with 121 that returned to work.

The exact timing of the arrival of COVID-19 to the United States and Central Massachusetts is unclear. However, Massachusetts reported its first case in March9, and UMASS reported its first admission on March 11th, 202010. This information is relevant because it suggests that hundreds of surgical procedures were performed at UMASS after the arrival of COVID-19 in Central Massachusetts. Given this, it is possible to calculate the post-operative incidence of COVID-19 in patients submitted to thoracic surgery. The incidence of post-operative COVID-19 is important because numerous studies have demonstrated high rates of morbidity and mortality in patients who contract COVID-19 in the post-operative period11-16. One study demonstrated post-operative mortality of 33% in patients who underwent lung resection who contracted COVID-19 in the post-operative period17.

Individuals with cancer have a higher risk of severe events, such as admission to the intensive care unit requiring invasive ventilation or death, in comparison with non-cancer patients (seven [39%] of 18 patients vs. 124 [8%] of 1,572 patients; Fisher's exact p=0·003)16. In the context of lung cancer, minimizing the risk of exposure to COVID-19 for patients while avoiding treatment delays has brought exceptional challenges to healthcare facilities. The fact that the symptoms presented by patients with lung cancer, as cough, dyspnea, and hemoptysis, are consistent with those that were presented with COVID-19, additionally slowed down proper diagnostics18.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its mitigation measures, as lockdown and social distancing, among others19, disrupted significantly healthcare systems worldwide, including the diagnosis and treatment of cancer19,20. These interruptions were particularly critical in oncology, as timely intervention is crucial. Prolonged delays may result in more advanced disease stages at diagnosis, reducing the effectiveness of treatment and negatively impacting survival rates21. The postponement of routine screenings, diagnostic procedures, and therapeutic interventions due to healthcare system strain and resource reallocation has exacerbated existing challenges in cancer care22.

Addressing these disruptions in cancer care required strategic adaptations in healthcare delivery, including the integration of telemedicine, prioritization of high-risk cases, and policy interventions to mitigate the long-term consequences of delayed cancer care. Cancer therapy is inherently complex, with outcomes heavily dependent on precise timing. Numerous oncology societies and health ministries have developed comprehensive guidelines for cancer management to support oncologists and patients in managing care during crises. The insights gained from these experiences should be utilized to refine and strengthen care models in preparation for future pandemics23.

The various subspecialties within surgical oncology needed to adapt to provide care in the context of the pandemic, which demanded patient care modifications. Telehealth has emerged as a feasible and effective strategy for managing cancer patients, securing its consideration as a standard component of surgical oncology practice24.

The term “Telehealth” is a broad term that refers to the use of digital and telecommunication technologies to provide a range of healthcare services, including clinical care, patient education and remote monitoring25,26. It encompasses both clinical and non-clinical applications, such as health education and mobile health (mHealth)27.

Telemedicine is a subset of telehealth that focuses on the remote delivery of clinical services, as diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up consultations, using video conferencing, mobile applications, and other digital platforms28.

These approaches facilitate long-distance interactions between patients and healthcare professionals, providing clinical care, guidance, educational resources, reminders, interventions, monitoring, and remote admissions29. Both have gained significant importance in improving healthcare access, particularly for rural and underserved populations, reducing costs, and enhancing patient-centered care30. Telemedicine, particularly video-consulting, has rapidly accelerated since the COVID-19 pandemic29.

Considering this scenario, this study aims to estimate the impact of adopting telemedicine for outpatient visits as a tool to reduce disease exposure for patients and providers and minimize the effect on the continuum of care for lung cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHOD

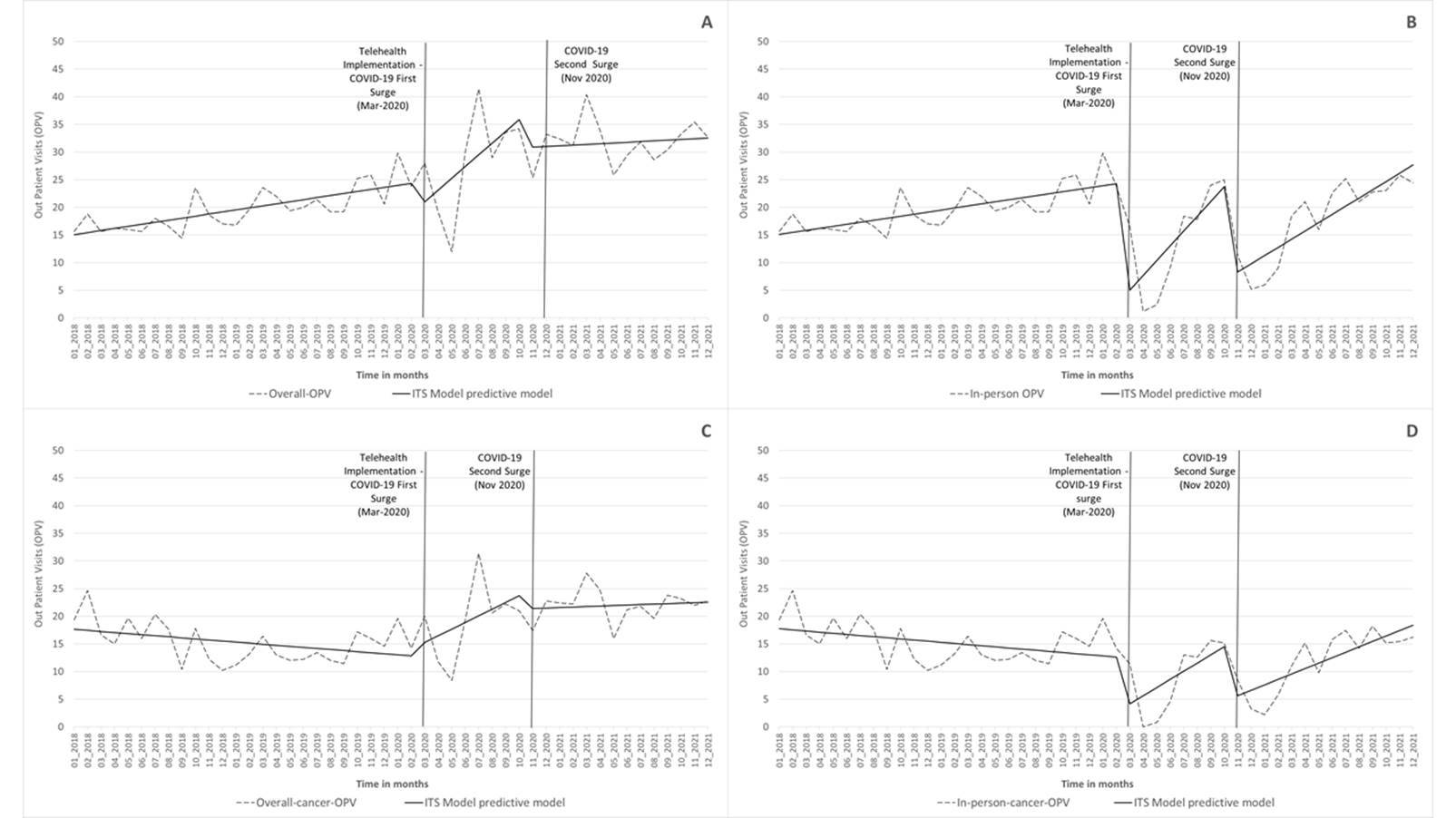

This longitudinal quasi-experimental study uses an interrupted time series (ITS) analysis to assess the effect of telemedicine outpatient visits (OPV) on minimizing the impact of COVID-19 on patient care. The data were extracted from the institutional electronic medical records (EMR) from January 2018 to December 2021 of the Division of Thoracic Surgery of the University of Massachusetts. It was analyzed considering the implementation of telemedicine services in the first and second waves of COVID-19 surges in Massachusetts in March and November 2020, respectively. The primary outcomes were an average of (A) monthly overall-OPV; (B) monthly in-person-OPV, (C) monthly overall-cancer-OPV, and (D) monthly in-person-cancer-OPV.

The ITS regression models31-35 were used to identify the effect of telemedicine implementation on the selected indicators. While estimating the effects, the ITS models adjust to preexisting trends in the period before the event of interest31. The segmented linear regression models were created using the "prais" command in STATA v 1732, examining linearity and autocorrelation within the series.

The ITS models were composed of three segments: I) baseline (January 2018 to February 2020), II) COVID-19 first surge and telemedicine implementation (March to October 2020), and III) COVID-19 second surge (November 2020 to December 2021).

The ITS segmented model terms are specified as follows31,32,35,36:

The time (t) is a continuous variable that specifies the time in months from the beginning of the observation period; Yt = result variable in month t; β0 = level at the start of the observation period; β1 = baseline trend; month = number of months since the start of the observation; β2 = level change at first COVID-19; intervention1t = month after the COVID-19 surge; β3 = trend change after the first COVID-19 surge; β4 = level change after second COVID-19 surge; intervenção2t = month after second COVID-19 surge; β5 = trend change after second COVID-19 surge and et = residual error.

The baseline segment was adjusted with two interruptions (the first surge and telemedicine implementation and the second COVID-19 surge) and two variable estimation trends. The intervention effects were quantified using two distinct variables: one representing the immediate change in the indicator level following the COVID-19 surges and the other capturing the alteration in the trend of the post-intervention segment. A sensitivity analysis, applying Durbin-Watson (dw) statistics, was performed to verify the existence of autocorrelation. The Prais-Winsten regression was the procedure that had the best fit32. The sensitivity analysis indicated that no autocorrelation was found. Regardless of the statistical significance, the models included all parameters because they rendered the best fit. To summarize the effects of the intervention, estimates of the relative changes for May 2020 and January 2021 were calculated.

The Institutional Review Board of the Medical School of the University of Massachusetts reviewed and approved the study, register IRB ID STUDY00000153.

RESULTS

From January 2018 to December 2021, 5,918 outpatient visits were included and analyzed. Female patients accounted for 55.3% of the visits, 87% were White, and the mean age was 66 years. Telemedicine visits represented 25.8% of the total visits and 27.7% of cancer-related visits. Female patients had a higher likelihood of having a telemedicine appointment, while White, Black, and Asian patients had a similar percentage of telemedicine utilization (26.3%, 25.0%, and 26.8%) (Table 1). White individuals are more likely to use telemedicine (OR=1.25 [ 95%CI 1.0 – 1.5]). Individuals who self-identified themselves as other races are less likely to use telemedicine. Among those, 67% also claimed they are Latinos. Non-Latinos have an increased likelihood of having a telemedicine appointment when compared to Latinos (OR=1.5 [ 95%CI 1.1 – 2.1]).

Telemedicine visits conducted by phone were more prevalent than telemedicine by video, age was not significantly different between telemedicine and non-telemedicine appointments. However, there was a relevant difference in the types of telemedicine appointments. The mean age for those who preferred a phone appointment was 67, while for those who used video was 63 (p < 0.050). Asians were more likely to use telemedicine video, and cancer-related consults were more likely to be performed by phone (Table 2).

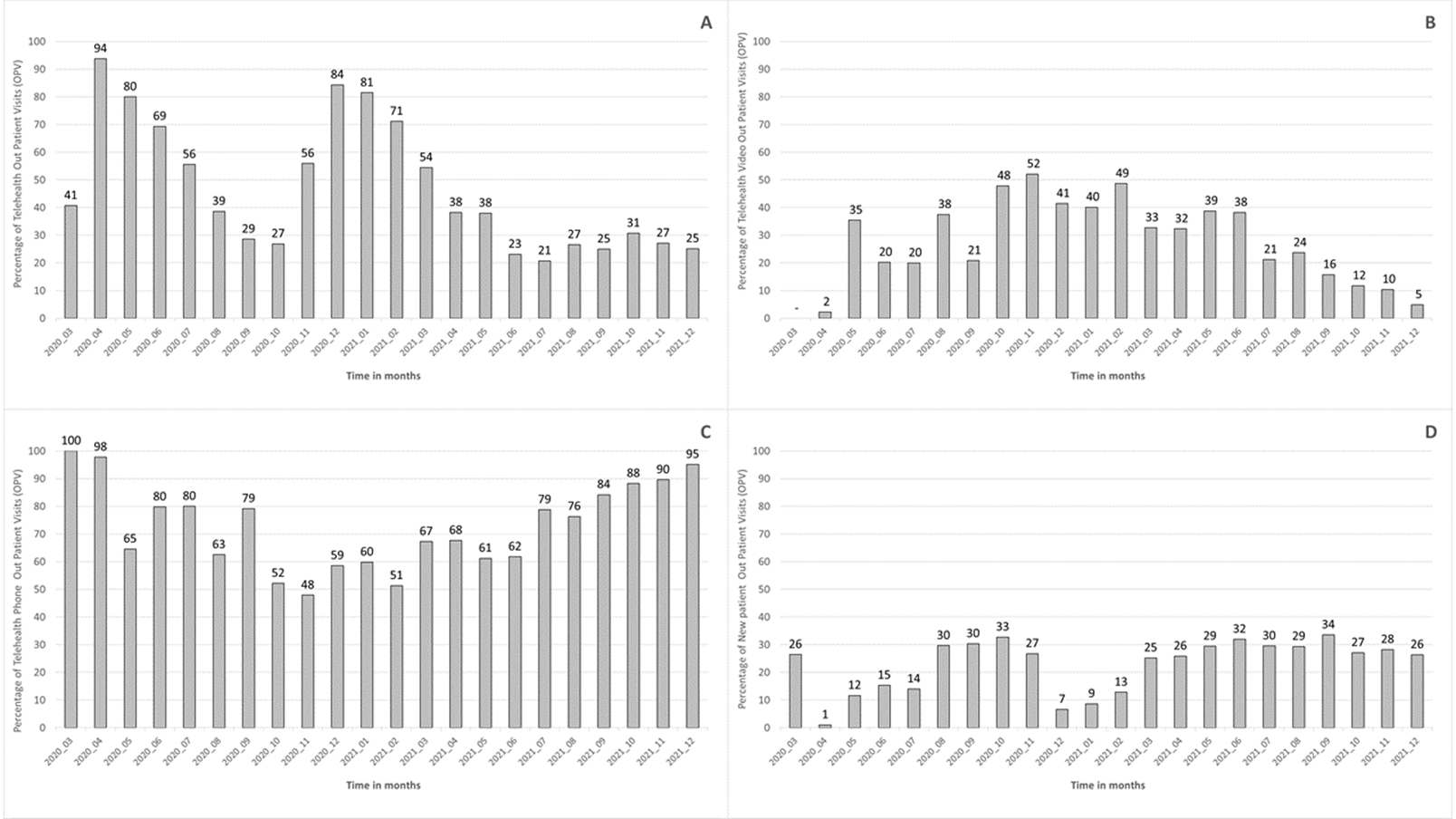

When analyzing the monthly distribution of telemedicine, it was observed that the overall percentage of telemedicine varied proportionally with the COVID-19 epidemiological situation. The growth in COVID-19 cases was followed by an increase in telemedicine utilization (Figure 1-A). It was also observed that most interactions occurred by phone, primarily for follow-up. (Figure 1 B, C, and D). After its implementation, the monthly percentage of telemedicine visits remained somewhat stable, maintaining levels around 20 to 25 % as a baseline.

For outcomes (A) and (C), which include the telemedicine visits, the COVID-19 surges did not have a statistically significant impact on the mean OPV (Figure 2) (Table 3). On the other hand, there was a statistically significant decline for in-person OPV overall (B) and cancer (D) following the policies implemented to reduce the spread of COVID-19. In the first COVID-19 surge, the use of telemedicine for outpatient visits prevented a decline in appointments, represented by the percentage of relative change of 59.1% (p = 0.001) overall and 40.9% (p = 0.019) for cancer. In the second surge (November 2020), these values were 64.4% (p = 0.001) for overall OPV and 59.8% for cancer (p = 0.001), respectively. (Figure 2) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The COVID-19 pandemic brought a variety of challenges for the healthcare system. Among them, the struggle to safely provide care for cancer patients. The current findings pointed out that over time, due to the implementation of telemedicine, the thoracic surgery service was able to successfully provide care for its patients, which was especially relevant for cancer patients where timely care is fundamental to survival.

In this study, no disparities in age have been observed, analogous to other studies37, but a relevant disparity was found for the Latino population, similar to other studies37-39. Future studies in the institution should attempt to identify the reasons for this discrepancy in the utilization of telemedicine. As described in the literature, it can be due to patient preference, difficulties in having an interpreter, challenges using the technology, and the availability of the technology38.

The use of telemedicine drastically impacted the healthcare delivery system, and a broader expansion of these services could be expected. However, implementing telemedicine services can be challenging, especially regarding reimbursement and existing laws limiting access that may prevent specific patient populations from accessing health through telemedicine. The COVID-19 pandemic led to recent relevant changes, as those made by the Center for Medicare Services, allowing broader reimbursement and, therefore, increasing access to telemedicine services for patients during the pandemic40. It is worth mentioning that low resources areas could benefit from implementing telemedicine beyond the duration of the crisis.

This study is based on a single academic institution, and its results might not be generalizable to the population. Additionally, this analysis is based on data from the electronic medical records and, therefore, does not capture the perceptions and challenges of the telemedicine implementation, neither from patients nor providers. Other socio-demographic variables as education, that could provide insight into health literacy, are not easily extracted from the electronic medical records. Using zip codes to extrapolate census data could be helpful in this context. Nonetheless, it would have limitations.

In the United States, telemedicine has become an essential tool in cancer care, particularly in improving access to specialists, facilitating timely diagnosis, and enhancing patient monitoring, especially in rural and underserved areas. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine in oncology was growing, but it was not widely adopted due to regulatory and reimbursement barriers. However, the pandemic accelerated the widespread use of telehealth technologies, and policies were temporarily relaxed, allowing for greater use of telemedicine in oncology41. Telemedicine has proven beneficial in multidisciplinary cancer care teams, where remote collaboration among specialists can enhance decision-making and patient management42.

In oncology, telemedicine services for follow-up care have proven effective in monitoring patients for recurrent cancers and providing ongoing support for symptom management, especially during the pandemic when in-person visits were restricted41,43,44.

In Latin America, telemedicine has become a critical tool in addressing cancer care challenges due to geographic barriers, limited access to oncology specialists, and disparities in healthcare resources. These efforts are essential in overcoming barriers to care in the region, where disparities in healthcare access and infrastructure often impede timely treatment45.

Despite its benefits, several challenges hinder telemedicine's full implementation and effectiveness in cancer care. These challenges include technological infrastructure limitations, digital literacy gaps, and regulatory barriers, particularly in countries where standardized telemedicine policies are but scarce.

Further, health disparities persist in many areas, where socio-economic status, education level, and geographical location influence the availability and utilization of telemedicine. Programs aimed at improving infrastructure, expanding broadband access, and enhancing digital literacy will be crucial to the future success of telemedicine in these regions.

CONCLUSION

Telemedicine has become an essential component of cancer care, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. It facilitated continued care and improved patient outcomes in underserved areas. Implementing telehealth technology allowed patients to safely receive care throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, positively impacting the maintenance of care for patients with cancer in a single thoracic surgery service.

Telemedicine is effective in follow-up care, especially for rural and remote populations. Adopting telehealth can expand access to care in the context of the pandemic and low-resource areas. Nevertheless, future studies should evaluate possible disparities regarding availability, equipment for accessing telehealth, and telemedicine usage for cancer patients, especially for the underserved population.

Additionally, it should explore and understand the perspectives and expectations of healthcare providers and patients and the challenges of using telehealth technology. This knowledge is fundamental to support a truthful learning health system in which internal data and experience are methodically integrated with external evidence. Applying this integrated knowledge aims to enhance healthcare delivery's quality, safety, and efficiency.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Department of Surgery at the UMass Chan Medical School. Worcester – Massachusetts – USA.

CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the study design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing and critical review with intellectual contribution They approved the final version to be published.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

There is no conflict of interests to declare.

FUNDING SOURCES

This work was developed with departmental funds from the Department of Surgery at the UMass Chan Medical School. Worcester – Massachusetts – USA.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Report of the WHO-China joint mission on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [Internet]. 2020 Feb 20 [cited 2025 Jan 25]. Available from:https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf

2. Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, et al. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):470-3. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9

3. Velavan TP, Meyer CG. The COVID‐19 epidemic. Trop med int health. 2020;25(3):278-80. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13383

4. Kolifarhood G, Aghaali M, Saadati HM, et al. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of COVID-19; a narrative review. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8(1):e41.

5. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199-207. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001316

6. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-42. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. Washington, D.C: CDC; [2020]. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the U.S. centers for disease control and prevention, COVID-19 Update for the United States,2020 May 10. [cited 2024 Mar 25]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. Washington, D.C: CDC; [2020]. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020 Feb 11. [cited 2020 May 25]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/dialysis/screening.html

9. Massachusetts Department of Public Health [Internet]. Boston: Mass.gov; [2020]. First presumptive positive case of COVID-19 identified by Massachusetts state public health laboratory. [cited 2020 Mar 25]. Available from: https://archives.lib.state.ma.us/server/api/core/bitstreams/eb0c8ef4-38f4-4451-aa5b-93584e75eaba/content

10. UMass Memorial Medical Center [Internet]. Worcester: UMass Memorial Health Care; [2020]. First coronavirus patient in Worcester County was treated at UMass Memorial Medical Center in Worcester. [Cited 2020 May 18]. Available from: https://www.umassmemorialhealthcare.org/umass-memorial-medical-center/first-coronavirus-patient-worcester-county-was-treated-umass-memorial-medical-center-worcester

11. Cai Y, Hao Z, Gao Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of seven cases infected with sars-cov-2 in the perioperative period of lung resection: a retrospective study from a single thoracic department in Wuhan, China. Preprint Lancet; 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3546042

12. Mehta V, Goel S, Kabarriti R, et al. Case fatality rate of cancer patients with COVID-19 in a New York Hospital System. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(7):935-41 doi: https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.cd-20-0516

13. Lei S, Jiang F, Su W, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;21:100331. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331

14. Harky A, Chiu CM, Yau THL, et al. Cancer patient care during COVID-19. Cancer Cell. 2020;37(6):749-50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2020.05.006

15. Jheon S, Ahmed AD, Fang VW, et al. General thoracic surgery services across Asia during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2020;28(5): 243-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0218492320926886

16. Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6

17. Cai Y, Hao Z, Gao Y, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in the perioperative period of lung resection: a brief report from a single thoracic surgery department in Wuhan, people’s republic of China. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(5):e66-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2020.04.003

18. Mojsak D, Dębczyński M, Kuklińska B, et al. Impact of COVID-19 in patients with lung cancer: a descriptive analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(2):1583. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021583

19. Sud A, Jones ME, Broggio J, et al. Collateral damage: the impact on outcomes from cancer surgery of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2020;31(8):1065-74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.05.009

20. Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(8):1023-34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30388-0

21. Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, et al. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1907-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31187-9

22. Richards M, Anderson M, Carter P, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care. Nat Cancer. 2020;1(6):565-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-020-0074-y

23. Alhalabi O, Subbiah V. Managing cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Trends Cancer. 2020;6(7):533-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2020.04.005

24. Gazivoda V, Greenbaum A, Roshal J, et al. Assessing the immediate impact of COVID-19 on surgical oncology practice: experience from an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center in the northeastern United States. J Surg Oncol. 2021;124(1):7-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.26475

25. Federal Communications Commission (USA) [Internet]. Washington, DC: FCC; [undated]. Telehealth, telemedicine, and telecare: what's what? [Cited 2025 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.fcc.gov/general/telehealth-telemedicine-and-telecare-whats-what

26. World Health Organization. Telemedicine: opportunities and developments in member state [Internet]. Geneva: WHO Regional Office for Africa; [2020]. [Cited 2025 Feb 21]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/telemedicine-opportunities-and-developments-member-state

27. Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154-61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1601705

28. Bashshur RL, Shannon GW, Bashshur N, et al. The empirical evidence for telemedicine interventions in mental disorders. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(2):87-113. doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2015.0206

29. Pardolesi A, Gherzi L, Pastorino U. Telemedicine for management of patients with lung cancer during COVID-19 in an Italian cancer institute: SmartDoc Project. Tumori. 2021;108(4):357-63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/03008916211012760

30. Krupinski EA, Bernard J. Standards and guidelines in telemedicine and telehealth. Healthcare. 2014;2(1):74-93. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare2010074

31. Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, et al. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299-309. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x

32. Linden A. Conducting Interrupted Time-series analysis for single- and multiple-group comparisons. Stata J. 2015;15(2):480-500. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1501500208

33. Fretheim A, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, et al. Interrupted time-series analysis yielded an effect estimate concordant with the cluster-randomized controlled trial result. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(8):883-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.03.016

34. Fretheim A, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, et al. A reanalysis of cluster randomized trials showed interrupted time-series studies were valuable in health system evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(3):324-33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.10.003

35. Zhang F, Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, et al. Methods for estimating confidence intervals in interrupted time series analyses of health interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(2):143-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.08.007

36. Zhang F, Wagner AK, Ross-Degnan D. Simulation-based power calculation for designing interrupted time series analyses of health policy interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(11):1252-61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.02.007

37. Stevens JP, Mechanic O, Markson L, et al. Telehealth use by age and race at a single academic medical center during the COVID-19 pandemic: retrospective cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(5):e23905. doi: https://doi.org/10.2196/23905

38. Paterson C, Bacon R, Dwyer R, et al. The role of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic across the interdisciplinary cancer team: implications for practice. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2020;36(6):151090. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2020.151090

39. Darrat I, Tam S, Boulis M, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in patient use of telehealth during the coronavirus disease 2019 surge. JAMA Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2021;147(3):287-95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2020.5161

40. Grenda TR, Whang S, Evans III NR. Transitioning a surgery practice to telehealth during COVID-19. Ann Surg. 2020;272(2):e168-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004008

41. Toni E, Ayatollahi H. An insight into the use of telemedicine technology for cancer patients during the Covid-19 pandemic: a scoping review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2024;24(104):1-24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-024-02507-1

42. Sirintrapun SJ, Lopez AM. Telemedicine in cancer care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:540-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_200141

43. Garavand A, Khodaveisi T, Aslani N, et al. Telemedicine in cancer care during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic mapping study. Health Technol. 2023;13:665-78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12553-023-00762-2

44. Garavand A, Aslani N, Behmanesh A, et al. Telemedicine in lung cancer during COVID-19 outbreak: a scoping review. J Educ Health Promot. 2022;11(1):348. doi: https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_50_22

45. Restrepo JG, Alarcón J, Hernández A, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with solid tumors living in rural and urban areas followed via telemedicine: experience in a highly complex latin american hospital. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(253):1-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10717-5

Recebido em 5/12/2024

Aprovado em 24/2/2025

Scientific-Editor: Anke Bergmann. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1972-8777

Table 1. Outpatient visits (OPV) profile by type of encounter, January 2018 to December 2021

|

In-person OPV |

Telehealth OPV |

Total of OPV |

|

Telehealth OPV2 |

||||

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

% |

|

|

Age [Mean] |

4,393 |

66 |

1,525 |

66 |

5,918 |

66 |

|

25.8% |

|

Female |

2,408a |

54.8% |

866a |

56.8% |

3,274 |

55.3% |

|

26.5% |

|

Asian |

82a |

1.9% |

30a |

2.0% |

112 |

1.9% |

|

26.8% |

|

Black or African American |

156a |

3.6% |

52a |

3.4% |

208 |

3.5% |

|

25.0% |

|

Other |

359a |

8.2% |

89b |

5.8% |

448 |

7.6% |

|

19.9% |

|

White |

3,796a |

86.4% |

1,354b |

88.8% |

5,150 |

87.0% |

|

26.3% |

|

Hispanic or Latino |

329a |

7.6% |

72b |

4.8% |

401 |

6.9% |

|

18.0% |

|

Cancer related consult |

2,889a |

65.8% |

1,107b |

72.6% |

3996 |

67.5% |

|

27.7% |

Note: Values in the same row and not sharing the same subscript significantly differ at p < .05 in the two-sided equality test for column proportions. Cells with no subscript are not included in the test. Tests assume equal variances.1.

1. Tests are adjusted for all pairwise comparisons within a row of each innermost sub-table using the Bonferroni correction.

2. The percentages presented in this column are the line percentages to identify the percentage of telehealth in each category.

Table 2. Telehealth Outpatient visits (OPV) profile by type, March 2020 to December 2021

|

|

Telehealth Phone |

Telehealth Video |

Total of Telehealth |

|||

|

|

N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

|

Age [Mean] |

1,083 |

67a |

442 |

63b |

1,525 |

66 |

|

Female |

632a |

58.4% |

234a |

52.9% |

866 |

56.8% |

|

Asian |

12a |

1.1% |

18b |

4.1% |

30 |

2.0% |

|

Black or African American |

37a |

3.4% |

15a |

3.4% |

52 |

3.4% |

|

Other |

65a |

6.0% |

24a |

5.4% |

89 |

5.8% |

|

White |

969a |

89.5% |

385a |

87.1% |

1,354 |

88.8% |

|

Hispanic or Latino |

50a |

4.7% |

22a |

5.1% |

72 |

4.8% |

|

Cancer related consult |

809a |

74.7% |

298b |

67.4% |

1,107 |

72.6% |

Note: Values in the same row and not sharing the same subscript differ significantly at p < .05 in the two-sided equality test for column proportions. Cells with no subscript are not included in the test. Tests assume equal variances.1

1. Tests are adjusted for all pairwise comparisons within a row of each innermost sub-table using the Bonferroni correction.

Figure 1. Percentage of telehealth distribution, (A) monthly percentage of telehealth-OPV; (B) monthly percentage of telehealth video-OPV; (C) monthly percentage of telehealth phone-OPV; (D) monthly percentage of new patients-OPV. March 2020 to December 2021