ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Factors Associated with Referral of Patients with Advanced Cancer Utilizing a Palliative Care Referral Protocol

Fatores Associados ao Encaminhamento de Pacientes com Câncer Avançado Utilizando um Protocolo de Encaminhamento para Cuidados Paliativos

Factores Asociados con la Derivación de Pacientes con Cáncer Avanzado Utilizando un Protocolo de Derivación a Cuidados Paliativos

https://doi.org/10.32635/2176-9745.RBC.2025v71n2.5015

Bianca Sakamoto Ribeiro Paiva1; Gabriela Chioli Boer2; Bruna Minto Lourenço3; Welinton Yoshio Hirai4; Carlos Eduardo Paiva5

1,3-5Instituto de Ensino e Pesquisa Hospital de Câncer de Barretos, Grupo de Pesquisas em Cuidados Paliativos e Qualidade de Vida (GPQual). Barretos (SP), Brasil. E-mails: bsrpaiva@gmail.com; brunaminto65@gmail.com; welinton.hirai@hospitaldeamor.com.br; caredupai@gmail.com. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2711-8346; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6594-9087; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8217-3383; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7934-1451

2Hospital de Câncer de Barretos, Instituto de Ensino e Pesquisa. GPQual. Faculdade de Ciências da Saúde de Barretos Dr. Paulo Prata (Facisb). Barretos (SP), Brasil. E-mail: gabriela.boer@hotmail.com. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3179-9014

Corresponding author: Bianca Sakamoto Ribeiro Paiva. Rua Antenor Duarte Vilella, 1331 – Dr. Paulo Prata. Barretos (SP), Brasil. CEP 14784-400. E-mail: bsrpaiva@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Numerous barriers hinder timely referral to palliative care (PC) leading to inadequate symptom management and diminished quality of life. Standardizing referral criteria is essential to improve access to PC, emphasizing the urgency of early referral for patient support. Brazilian experts created the Palliative Care Referral Protocol (PCRP), a tool to categorize oncology patients based on clinical urgency, prioritizing appointments within 90, 45, and 15 days according to the severity. Objective: Evaluate factors influencing referral patterns of advanced cancer patients using a palliative care referral protocol. Method: Retrospective cohort study conducted at Hospital de Câncer de Barretos (Barretos, São Paulo, Brazil). Data from electronic medical records of cancer patients who met the inclusion criteria were analyzed using three instruments: Sociodemographic and Clinical Patient Characterization Questionnaire; Assessment Questionnaire of Referrals through PCRP according to clinical performance; Evaluation Questionnaire of Referrals without the PCRP. Statistical analyses utilized IBM-SPSS v.27.0, R v.4.3.2 software, and GGPLOT2 library, with significance of p < 0.05. Results: 1,492 patient records were identified, 323 were randomized (226 with PCRP and 97 without PCRP). PCRP-referred patients were predominantly females, with higher education, diagnosed with digestive cancer as primary tumor. Predictors for PC referral included exclusive PC treatment, higher KPS, and yellow performance group (ECOG). Referral according to the protocol were more detailed and justified. Conclusion: Targeted interventions and educational initiatives focused to healthcare providers are required to ensure timely access, emphasizing its key role in clinical practice. Longitudinal trials are needed to further validate the effectiveness of PCRP in clinical practice.

Key words: Palliative Care; Clinical Protocols; Patient Selection.

RESUMO

Introdução: Diversas barreiras impedem o encaminhamento oportuno para cuidados paliativos (CP), levando ao manejo inadequado dos sintomas e à diminuição da qualidade de vida. Padronizar critérios de encaminhamento é essencial para melhorar o acesso aos CP. Encaminhamentos precoces são fundamentais para o suporte ao paciente. Especialistas elaboraram o Protocolo de Encaminhamento para Cuidados Paliativos (PECP), que categoriza pacientes oncológicos com base na urgência clínica, priorizando consultas em 90, 45 e 15 dias, conforme a gravidade. Objetivo: Avaliar fatores que influenciam padrões de encaminhamento para cuidados paliativos. Método: Estudo de coorte retrospectivo realizado no Hospital de Câncer de Barretos (Barretos, São Paulo, Brasil). Dados de prontuários eletrônicos de pacientes com câncer que atendiam aos critérios de inclusão foram analisados utilizando três instrumentos: Questionário de Caracterização Sociodemográfica e Clínica do Paciente; Questionário de Avaliação dos Encaminhamentos pelo PECP conforme desempenho clínico; Questionário de Avaliação de Encaminhamentos sem o protocolo PECP. Análises estatísticas utilizaram os softwares IBM-SPSS v.27.0, R v.4.3.2 e biblioteca GGPLOT2, com significância definida de p<0,05. Resultados: Foram identificados 1.492 prontuários pacientes, 323 foram randomizados (226 com PECP, 97 sem PECP). Mulheres diagnosticadas com câncer do aparelho digestivo com maior escolaridade predominaram entre os pacientes encaminhados pelo PECP. Os preditores para encaminhamento foram tratamento exclusivo para CP, maior KPS e grupo de desempenho amarelo (ECOG). Os encaminhamentos realizados pelo protocolo foram mais detalhados e justificados. Conclusão: Intervenções direcionadas e iniciativas educacionais voltadas para profissionais de saúde são necessárias para garantir acesso oportuno, enfatizando seu papel fundamental na prática clínica. Ensaios longitudinais são necessários para validar ainda mais a eficácia do PECP na prática clínica.

Palavras-chave: Cuidados Paliativos; Protocolos Clínicos; Seleção de Pacientes.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Numerosas barreras dificultan la derivación oportuna hacia cuidados paliativos (CP), resultando en una gestión inadecuada de los síntomas y menor calidad de vida. Estandarizar los criterios de derivación es fundamental para mejorar el acceso a los CP. Especialistas desarrollaron el Protocolo de Derivación a Cuidados Paliativos (PDCP), herramienta que clasifica a los pacientes oncológicos según la urgencia clínica, priorizando citas en 90, 45 y 15 días. Objetivo: Evaluar los factores que influyen en los patrones de derivación a los cuidados paliativos. Método: Este estudio de cohorte retrospectivo se llevó a cabo en el Hospital de Cáncer de Barretos (Barretos, São Paulo, Brasil). Basado en datos de historias clínicas electrónicas. Fueron analizadas utilizando tres cuestionarios: Caracterización Sociodemográfica y Clínica del Paciente; Evaluación de Derivaciones a través del PDCP según el desempeño clínico; Evaluación de Derivaciones sin el protocolo PDCP. Los análisis estadísticos se realizaron utilizando los softwares IBM-SPSS v.27.0, R v.4.3.2 y la biblioteca GGPLOT2, con significación p<0,05. Resultados: Se identificaron 1492 registros de pacientes; 323 fueron aleatorizados (226 con PDCP; 97 sin PDCP). Los pacientes derivados con PDCP eran predominantemente mujeres diagnosticadas con cáncer del aparato digestivo con educación superior. Los predictores para derivación incluyeron, tratamiento exclusivo en CP, mayor KPS y grupo de desempeño amarillo. Las derivaciones realizadas con el protocolo fueron más detalladas y justificadas. Conclusión: Se necesitan intervenciones específicas e iniciativas educativas dirigidas a los proveedores de atención médica para garantizar el acceso oportuno, enfatizando su papel fundamental en la práctica clínica. Se necesitan ensayos longitudinales para validar aún más la eficacia del PDCP en la práctica clínica.

Palabras clave: Cuidados Paliativos; Protocolos Clínicos; Selección de Paciente.

INTRODUCTION

The International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care (IAHPC) suggests that Palliative Care (PC) is a form of holistic and multidimensional support for individuals experiencing health-related suffering due to serious illnesses and those nearing the end of life, aiming to improve symptoms and consequently enhance the quality of life for patients, their families, and caregivers¹. This type of care should be initiated as soon as any manifestation of a life-threatening illness arise, alongside with curative measures, to gain significance and prominence in the patient's therapeutic plan as these curative measures diminish in effectiveness.

However, there are many barriers that can hinder the referral of patients to PC, since patients and their families usually associate PC as a place to die, inadequate knowledge either patients and even healthcare professionals have about PC goals, challenging prognostic estimates and limited time to educate patients about the benefits of timely referral to PC².

A Brazilian study³ revealed that the majority of patients attended palliative care consultations before passing away, and the number of patients with late consultations increased over the course of the study. Patients with delayed referrals could have received palliative care sooner.

Patients who are not timely referred to PC may experience inadequate symptom control, emotional and psychological stress, treatment decisions not aligned with their wishes and social isolation. Furthermore, the lack of palliative care can contribute to an overall decrease in their quality of life, as these measures are designed to improve physical, emotional, and social well-being, even in face of a serious illness4,5.

There are difficulties in defining the ideal timing for recommending referral to PC6,7. To date, few studies have focused on developing specific referral PC protocols. Some authors believe that the referral should be done automatically based on well-defined clinical criteria8-11. In this regard, Hui et al.8 conducted a consensus using the Delphi methodology, proposing major and minor PC referral criteria.

In line with these findings and the need for more objective measures for this assessment, researchers and experts in clinical oncology and palliative care from a reference oncology hospital in Brazil developed the Palliative Care Referral Protocol – PCRP². The PCRP is a screening tool comprised of items that determine the timely referral of oncology patients to PC on an outpatient basis, categorizing the risk of these patients into three distinct priorities (appointments scheduled within 90, 45, and 15 days).

The PCRP is divided into two parts: the first is a checklist that must be filled out during the outpatient oncology consultation whose criteria are treatment timing, severe physical and emotional symptoms, caregiver distress, difficulty in decision-making, among others. If any criteria is marked on the checklist, the patient should be referred to outpatient PC. The second part classifies the patient according to the priority for scheduling the consultation, using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS) tool divided in three groups: green group (the first consultation should be scheduled within 90 days); yellow group (the first consultation should be scheduled within 45 days); and red group (the first consultation should be scheduled within 15 days). The use of PCRP has reduced both the time between referral and first consultation at PC and the number of missed appointments. Furthermore, the protocol assisted in triaging patients, so that those with worse clinical conditions received earlier attention2.

A study evaluated the impact of early referral to palliative care on the quality of end-of-life care provided to patients. In this study, patients referred earlier to palliative care had fewer emergency visits, hospitalizations, and in-hospital deaths compared to patients with late referrals. Additionally, it was assessed that patients referred in the outpatient setting experienced an improvement in the quality of end-of-life care compared to those referred in the hospital setting¹². Another study also concluded that establishing clear screening and identification processes for referral to palliative care can increase the number of referrals and, consequently, the patients’ quality of life13; and that referral criteria should be adapted to each institution, considering patient profiles and the type of care that can be provided13,14.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the factors associated with the referral of patients with advanced cancer utilizing the PCRP.

METHOD

Retrospective cohort study from November 2021 to December 2022. The data were collected from patient records at the Hospital de Câncer de Barretos, an oncology reference public institution in Latin America that assists patients from all five Brazilian regions.

The inclusion criteria were patients aged ≥ 18 years, of both sexes, in oncologic treatment for breast, genitourinary, digestive, head and neck/thoracic cancers, sarcoma, melanoma and hematological cancer. Patients with incomplete records and those who refused to participate were excluded.

The sample of 323 patients, 226 utilizing the PCRP (70%) and 97 non-PCRP (30%) was calculated by probability, with a 95% confidence interval for the frequency of patients with advanced cancer referred to palliative care using the PCRP, with a margin of error of 5%.

The information was gathered using the TASY15 software – a hospital management software to streamline clinical, administrative and financial processes – and assessed upon the completion of PCRP clinical notes found in the medical records. Data storage occurred on the RedCap16 platform (Research Electronic Data Capture), which is a secure and online electronic data capture and management software, safeguarding and preserving individual data in compliance with the General Data Protection Law17. For data not found in the patient's medical record, the option "unknown" was marked during the questionnaire completion.

The questionnaires utilized to collect the data were:

(1) Sociodemographic and Clinical Patient Characterization Questionnaire: gender, ethnicity, marital status, religion, education level, city of origin, current city of residence, histology type, tumor staging.

(2) Assessment Questionnaire of Referrals through PCRP according to clinical performance: type of cancer, patient's clinical performance group, reason for referral, time elapsed between referral and first consultation at PC units. Since its development and the publication of the article, the PCRP has been integrated into the daily routine of the Hospital de Câncer de Barretos, as a tool for referring cancer patients to PC.

(3) Evaluation Questionnaire of Patients Referred to Palliative Care without the PCRP protocol: type of cancer, patient's clinical performance group (ECOG), reason for referral, time elapsed between referral and first consultation at PC units.

Qualitative variables were analyzed through measures of frequency and proportions and minimum and maximum values, median, mean and standard deviation for the quantitative variables. The chi-square test or Fisher's exact test (non-parametric) and the Wilcoxon test were applied for group comparisons. The normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Causality effects with the outcome variable (with/without PCRP) were examined using univariate and multivariate logistic regression. IBM-SPSS18 v.27.0 and R19 v.4.3.2 software were utilized for the analyzes, and the GGPLOT2 library20 for graphical analyses. A significance level of 5% (0.05) was adopted for all tests.

The Ethics Committee of “Hospital de Câncer de Barretos” (Barretos, São Paulo, Brazil) approved the study, report number 6.017.427/2023 (CAAE (submission for ethical review): 67624823.3.0000.5437). Patient consent to authorize the collection of their data from medical records was obtained via audio-recorded phone calls, in compliance with Directive number 46621, dated December 12, 2012 of the National Health Council.

RESULTS

In all, 1,492 patients charts have been identified, of which 323 were randomized (226 with PCRP and 97 without PCRP). Of these, 255 had already deceased and were automatically included. Nine alive patients refused to participate and 68 were excluded for not meeting the eligibility criteria.

Women predominated among the patients referred to PC utilizing the PCRP, accounting for 54% (122), with education from 8 to 11 years (105 patients, 45.8%); the majority of patients without PCRP were males (50 patients, 52%), with less than 8 years of education (47 patients, 48.1%). Ethnicity, marital status, religion, and professional activity were evenly distributed among men and women. Digestive cancer accounted for 75 (33%) of the referrals to PC utilizing PCRP, followed by breast cancer with 47 (21%). Metastasis, evaluation by ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status), and KPS (Karnofsky Performance Status) were similar between the groups (Table 1).

Among patients with PCRP, the majority fell into the yellow group (103, 46%), meaning the first appointment was scheduled within 45 days, and upon matching with patients referred without PCRP (using the patient's ECOG at the consultation), 39 (41%) were assigned to the green group. The association between PCRP and non-PCRP groups had p = 0.036. Digestive cancer was the main cause of referral of 75 (33%) patients utilizing PCRP, but for head and neck/thorax cancer, 40 patients (41%) were referred without the PCRP. The means of time between diagnosis and referral, referral and first consultation, and between referral and patient death were evaluated; however, these associations did not show statistical significance (p = 0.8; p = 0.2; p = 0.082 respectively) (Table 2).

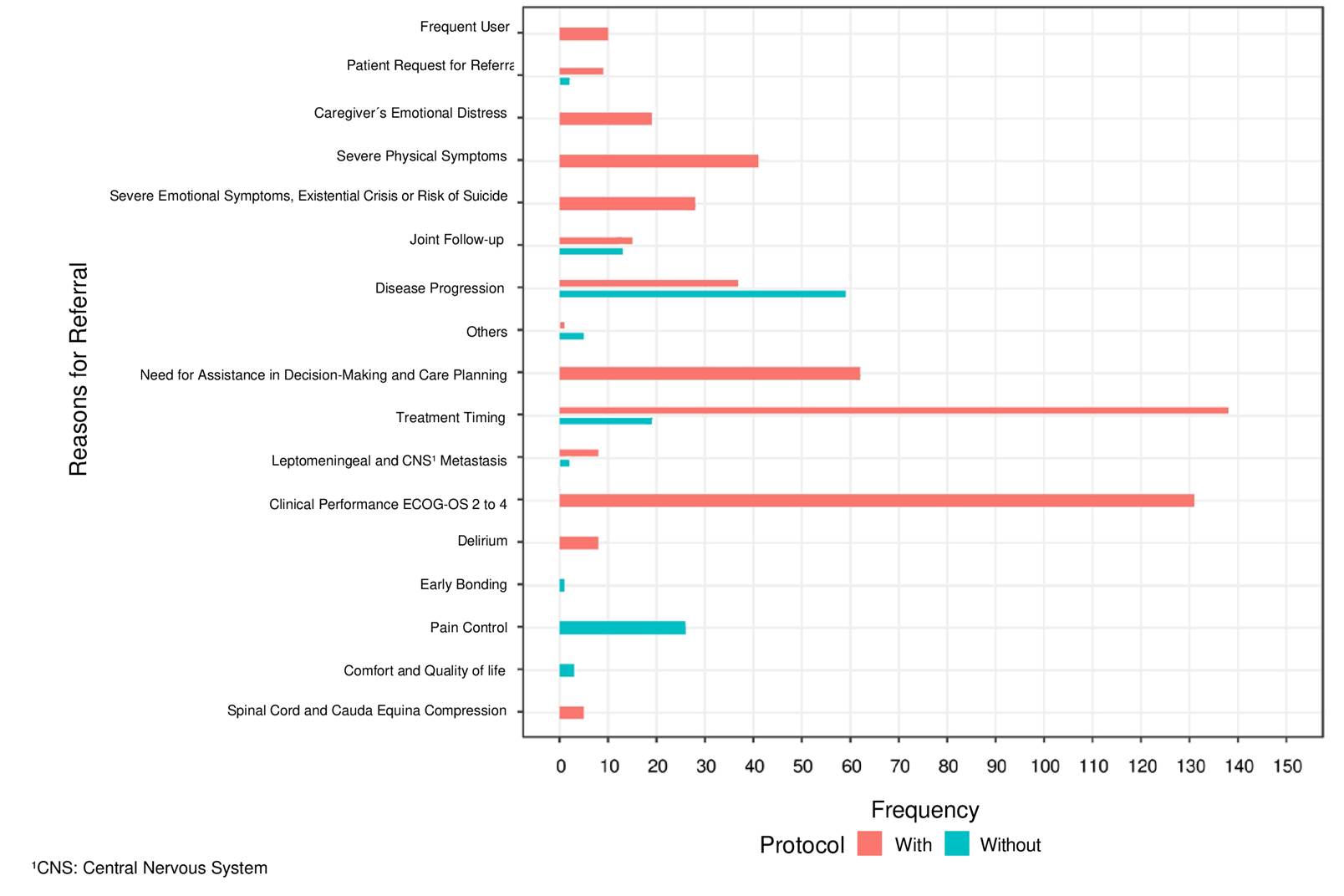

Referrals utilizing PCRP were better justified and detailed, emphasizing the treatment timing, patient's clinical performance, need for decision-making assistance, and care planning, but referrals without the PCRP were general, containing disease progression, pain management, treatment timing, and follow-up. Figure 1 portrays the distribution of referrals with and without PCRP and frequency.

The univariate analysis of clinical and sociodemographic predictors associated with palliative care with and without PCRP identified significant associations with specialized palliative care treatment (p = 0.020), KPS greater than 60% (p < 0.001), yellow performance group (p = 0.016) and other types of cancer (p = 0.023), as described and highlighted in Table 3.

Yellow performance group (p = 0.006), melanoma (p = 0.043) and head and neck/thorax cancers (p < 0.001) presented lower odds of referral compared to patients with different characteristics, as observed in the multivariate analysis described in Table 4.

DISCUSSION

The results highlight the patterns and factors associated with the referral of patients with advanced cancer to PC. Patients with digestive cancer accounted for a substantial proportion of referrals, especially when the PCRP was utilized. It is noteworthy that the clinical profiles of patients referred with and without the PCRP were equivalent in terms of the criteria described in the protocol, which implies in a possible standardization of referral practices.

Most of the patients referred based on the PCRP were classified in the yellow group, i.e., immediate appointment scheduling within 45 days. A significant proportion of patients referred without the PCRP fell into the green group, indicating a comparable level of clinical urgency and need for palliative care assistance. The statistically significant association between the PCRP and non-PCRP groups (p = 0.036) indicates the impact of using standardized protocols to influence the referral patterns of cancer patients to PC, potentially ensuring adequate and timely access for patients with advanced cancer.

The clinical profile of cancer patients referred for palliative care reflects a combination of advanced disease, severe symptoms, and significant decline in functional status. The optimal referral timing remains uncertain, depending on the patient and the healthcare system22. However, its benefits have shown that patients referred earlier experienced significantly better outcomes in their last 30 days of life3,23, as a remarkable reduction of aggressive end-of-life measures, lower rates of emergency room visits and hospitalizations, less chemotherapy near death, and fewer intensive care unit admissions; additionally, earlier palliative care was associated with statistically and clinically significant reductions in symptom severity and improved quality of life12,22,24-27.

Rather than advocating earlier palliative care for every patient since some of them may not need this type of care22,26,28, provide “timely palliative care, selecting the right patient for the right level of intervention at the right time"22 appears to be the best conduct. The PCRP can be a tool to determine the appropriate referral timing to PC.

It was observed that disease progression and pain control were the most common reasons for not using PCRP, whereas treatment timing and performance status were the most frequent reasons for its use. Studies evaluating the criteria for referring patients to PC units have identified several key factors, as the presence of complex physical and psychosocial symptoms, the need for refractory symptom management, and limited prognosis, among others. These studies underscore the importance of a careful and multidimensional approach to referring patients to PC8,29-31. In their study, Hui et al.8 highlight that if patients had been referred based on internationally agreed-upon standardized criteria31, the time between referral and consultation would have been reduced by approximately four months.

Analysis of the factors associated with the referral of cancer patients to palliative care provides important information about the complex interaction of clinical and sociodemographic variables that can influence decision-making processes32,33.

In addition, the analysis revealed that certain types of cancer, such as melanoma and head and neck/thorax, are associated with lower chances of referral to palliative care, highlighting the importance of understanding referral patterns specific to each type of cancer.

Barriers to timely palliative care referrals, such as limited awareness of its benefits, concerns about prognosis, and reluctance to discuss end-of-life issues, are frequently observed across different oncology specialties. These challenges can delay appropriate care and negatively impact patients' quality of life. Addressing these gaps requires targeted interventions and educational initiatives for healthcare providers, ensuring equitable access to palliative care regardless of patients' clinical and sociodemographic factors34.

Overall, the findings highlight the need for targeted interventions and education initiatives for healthcare providers to ensure equitable access to palliative care, regardless of their clinical and sociodemographic characteristics.

The retrospective design which may lead to reporting bias and potential incomplete and inaccurate data are the study limitations. As the data were obtained from a single site, the generalization of the results may be limited, in addition to potential differences of implementation of the PCRP by healthcare professionals due to their individual training, experience, and attitude towards PC.

CONCLUSION

The complexities of palliative care referrals have been discussed, highlighting the distinctions between patients referred with and without the PCRP. The results indicate that referrals utilizing PCRP are more comprehensively justified, potentially enhancing the overall quality of care. Significant predictors for palliative care referral included patient-centered palliative care treatment, higher KPS, and categorization into the yellow performance group. Furthermore, the similarities of clinical profiles between the groups suggest the necessity of consistent referral practices. Understanding these dynamics can improve patient outcomes and streamline oncology palliative care processes. Future researches should focus on optimizing referral criteria to ensure timely and effective interventions for all patients.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

There is no conflict of interests to declare.

FUNDING SOURCES

This work was funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) [grant number 2022/13598-0].

CONTRIBUTIONS

Bianca Sakamoto Ribeiro Paiva contributed to the study design, interpretation of the data, literature review and writing of the article. Gabriela Chioli Boer contributed to data collection, interpretation of the data, literature review and writing of the article. Bruna Minto Lourenço contributed to data collection, literature review and writing of the article. Welinton Yoshio Hirai contributed to the interpretation of the data and writing of the article. Carlos Eduardo Paiva contributed to the study design, interpretation of the data, literature review and writing of the article. All the authors approved the final version for publication.

REFERENCES

1. Osman H, Shrestha S, Temin S, et al. Palliative care in the global setting: ASCO resource-stratified practice guideline. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1-24. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1200/JGO.18.00026

2. Paiva CE, Paiva BSR, Menezes D, et al. Development of a screening tool to improve the referral of patients with breast and gynecological cancer to outpatient palliative care. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;158(1):153-7. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.04.701

3. Valentino TCO, Paiva BSR, Oliveira MA, et al. Factors associated with palliative care referral among patients with advanced cancers: a retrospective analysis of a large Brazilian cohort. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(6):1933-41. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-4031-y

4. Freitas R, Oliveira LC, Mendes GLQ, et al. Barreiras para o encaminhamento para o cuidado paliativo exclusivo: a percepção do oncologista. Saúde debate.2022;46(133):331-45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-1104202213306

5. Cherny NI, Fallon M, Kaasa S, et al. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780198821328.001.0001

6. Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(17):1616-25. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1204410

7. Floriani CA, Schramm FR. Palliative care: interfaces, conflicts and necessities. Ciênc saúde coletiva. 2008;13(sup2):2123. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1590/s1413-81232008000900017

8. Hui D, Mori M, Watanabe SM, et al. Referral criteria for outpatient specialty palliative cancer care: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):e552-e9. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30577-0

9. Nguyen L, De la Cruz M, Hui D, et al. Frequency and predictors of patient deviation from prescribed opioids and barriers to opioid pain-management in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45(3):506-16. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.023

10. Gobatto CA, Araujo TCCF. Religiosidade e espiritualidade em oncologia: concepções de profissionais da saúde. Psicol USP. 2013;24(1):11-34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-65642013000100002

11. Davis MP, Temel JS, Balboni T, et al. A review of the trials which examine early integration of outpatient and home palliative care for patients with serious illnesses. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4(3):99-121. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2224-5820.2015.04.04

12. Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120(11):1743-9. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28628

13. Kirolo I, Tamariz L, Schultz EA, et al. Interventions to improve hospice and palliative care referral: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(8):957-64. doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0503

14. Hui D, Meng YC, Bruera S, et al. Referral criteria for outpatient palliative cancer care: a systematic review. Oncologist. 2016;21(7):895-901. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0006

15. TASY [Internet]. Versão EMR HTML5. [São Paulo]: Philips; ©2004-2025. [Acess 2024 jun 25]. Available from: https://www.philips.com.br/

16. REDCap [Internet]. Version 15.2.1. Nashville: Vanderbilt University; 2024. [acess 2024 jun 29]. Available from: https://redcap.vanderbilt.edu/

17. Presidência da República (BR). Lei nº 13.709, de 14 de agosto de 2018. Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados Pessoais (LGPD). Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF. 2018 ago 14; Seção I.

18. SPSS®: Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) [Internet]. Version 27.0. [Nova York]. International Business Machines Corporation. [acess 2024 agu 9]. Disponível em: https://www.ibm.com/br-pt/spss?utm_content=SRCWW&p1=Search&p4=43700077515785492&p5=p&gclid=CjwKCAjwgZCoBhBnEiwAz35Rwiltb7s14pOSLocnooMOQh9qAL59IHVc9WP4ixhNTVMjenRp3-aEgxoCubsQAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds

19. R: The R Project for Statistical Computing [Internet]. Version 4.3.2 [place unknown]: The R foundation. 2021 nov 2 - [acess 2022 sept 6]. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/

20. Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2016. doi: https: //doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-98141-3

21. Conselho Nacional de Saúde (BR). Resolução n° 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. Aprova as diretrizes e normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF. 2013 jun 13; Seção I:59.

22. Hui D, Hannon BL, Zimmermann C, et al. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(5):356-76. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.3322/caac.21490

23. Haun MW, Estel S, Rucker G, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):Cd011129. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011129.pub2

24. Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2104-14. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.16840

25. Hausner D, Tricou C, Mathews J, et al. Timing of palliative care referral before and after evidence from trials supporting early palliative care. Oncologist. 2021;26(4):332-40. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1002/onco.13625

26. Ziegler LE, Craigs CL, West RM, et al. Is palliative care support associated with better quality end-of-life care indicators for patients with advanced cancer? A retrospective cohort study. BMJ open. 2018;8(1):e018284. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018284

27. Pellizzari M, Hui D, Pinato E, et al. Impact of intensity and timing of integrated home palliative cancer care on end-of-life hospitalization in Northern Italy. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(4):1201-07. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3510-x

28. Jang RW, Krzyzanowska MK, Zimmermann C, et al. Palliative care and the aggressiveness of end-of-life care in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(3):dju424. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju424

29. Hui D, Anderson L, Tang M, et al. Examination of referral criteria for outpatient palliative care among patients with advanced cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2019. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04811-3

30. Cuviello A, Yip C, Battles H, et al. Triggers for palliative care referral in pediatric oncology. Cancers. 2021;13(6):1419. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13061419

31. Iqbal J, Sutradhar R, Zhao H, et al. Operationalizing outpatient palliative care referral criteria in lung cancer patients: a population-based cohort study using health administrative data. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(5):670-7. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0515

32. Hui D, Heung Y, Bruera E. Timely palliative care: personalizing the process of referral. Cancers (basel). 2022;14(4):1047. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.3390/cancers14041047

33. Wong A, Vidal M, Prado B, et al. Patients' perspective of timeliness and usefulness of an outpatient supportive care referral at a comprehensive cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(2):275-81. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.04.027

34. Dalberg T, McNinch NL, Friebert S. Perceptions of barriers and facilitators to early integration of pediatric palliative care: a national survey of pediatric oncology providers. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(6):e26996. doi: https://www.doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26996

Recebido em 3/12/2024

Aprovado em 22/1/2024

Associate-editor: Livia Costa de Oliveira. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5052-1846

Scientific-editor: Anke Bergmann. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1972-8777

Table 1. Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of PCRP and non-PCRP patients

|

Characteristics |

PCRP¹, n = 226 (%)²

|

Non-PCRP², n = 97 (%)²

|

|

Sex |

|

|

|

Female |

122 (54) |

47 (48) |

|

Male |

104 (46) |

50 (52) |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

White |

162 (72) |

71 (73) |

|

Brown |

50 (22) |

21 (22) |

|

Black |

6 (2.7) |

5 (5.2) |

|

Yellow |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

|

Ignored |

6 (2.7) |

0 (0) |

|

Unknown |

1 |

0 |

|

Marital status |

|

|

|

Single |

32 (14) |

15 (15) |

|

Married |

110 (49) |

56 (58) |

|

Consensual marriage |

21 (9.3) |

8 (8.2) |

|

Divorced |

32 (14) |

5 (5.2) |

|

Widow/Widower |

30 (13) |

13 (13) |

|

Ignored |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

|

Religion |

|

|

|

Catholic |

142 (63) |

65 (67) |

|

Evangelical |

56 (25) |

20 (21) |

|

Spiritualist |

7 (3.1) |

2 (2.1) |

|

Jehovah’s Witness |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

|

None, but believe in God |

2 (0.9) |

1 (1.0) |

|

Other |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

|

Ignored |

16 (7.1) |

8 (8.2) |

|

Unknown |

1 |

0 |

|

Education |

|

|

|

< 8 years |

97 (43.3) |

47 (48.1) |

|

8 - 11 years |

105 (45.8) |

38 (40.1) |

|

>12 years |

19 (8.5) |

11 (11.4) |

|

Ignored |

5 (2.2) |

1 (1.0) |

|

Professional activity |

|

|

|

Retired |

182 (81) |

72 (74) |

|

Active (including housekeeping) |

32 (14) |

19 (20) |

|

Ignored |

11 (4.9) |

6 (6.2) |

|

Unknown |

1 |

0 |

|

Type of cancer |

|

|

|

Digestive |

75 (33) |

21 (22) |

|

Breast |

47 (21) |

9 (9.4) |

|

Urology |

34 (15) |

8 (8.3) |

|

Chest |

20 (8.8) |

22 (23) |

|

Gynecology |

17 (7.5) |

5 (5.2) |

|

Melanoma/Sarcoma |

16 (7.1) |

9 (9.4) |

|

Head and neck |

14 (6.2) |

18 (19) |

|

Hematology |

3 (1.3) |

4 (4.2) |

|

Distant metastasis |

|

|

|

Yes |

192 (85) |

70 (72) |

|

No |

31 (14) |

22 (23) |

|

Ignored |

2 (0.9) |

5 (5.2) |

|

Unknown |

1 |

0 |

|

Current treatment |

|

|

|

Palliative care and standard cancer treatment |

106 (47) |

40 (41) |

|

Exclusive palliative care |

103 (46) |

55 (57) |

|

Standard oncological treatment |

14 (6.3) |

1 (1.0) |

|

Without treatment |

1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

|

Ignored |

0 (0) |

1 (1.0) |

|

Unknown |

2 |

0 |

|

Performance Status Scale (ECOG) |

|

|

|

ECOG 0: Normal activity |

4 (1.8) |

4 (4.1) |

|

ECOG I: Symptoms of the disease, but walks and has a normal day-to-day life |

39 (17) |

16 (16) |

|

ECOG II: Out of bed more than 50% of the time |

47 (21) |

20 (21) |

|

ECOG III: In bed more than 50% of the time, requiring more intensive care |

50 (22) |

20 (21) |

|

ECOG IV: Totally confined to bed or chair |

86 (38) |

35 (36) |

|

Ignored |

0 (0) |

2 (2.1) |

|

Performance Status Scale (KPS) |

|

|

|

10-20% (4 points) |

87 (38) |

34 (35) |

|

30-50% (2,5 points) |

73 (32) |

29 (30) |

|

More than 60% (0 points) |

66 (29) |

33 (34) |

|

Unknown |

0 |

1 |

¹PCRP = Palliative Care Referral Protocol; 2n (%); median (IQR).

Table 2. Percentage and clinical characteristics of PCRP and non-PCRP patients

|

Characteristics |

PCRP n = 226 (%)1

|

Non-PCRP n = 97(%)1

|

p -value2 |

|

Performance group |

|

|

0.036 |

|

Green (first consultation should be scheduled within 90 days) |

62 (27) |

39 (41) |

|

|

Yellow (first consultation should be scheduled within 45 days) |

103 (46) |

31 (33) |

|

|

Red (first consultation should be scheduled within 15 days) |

61 (27) |

25 (26) |

|

|

Unknown |

0 |

2 |

|

|

Type of cancer |

|

|

<0.001 |

|

Digestive |

75 (33) |

23 (24) |

|

|

Breast and gynecological |

64 (28) |

14 (14) |

|

|

Head and neck/chest |

37 (16) |

40 (41) |

|

|

Urology |

33 (15) |

8 (8.2) |

|

|

Sarcoma |

11 (4.9) |

5 (5.2) |

|

|

Melanoma |

3 (1.3) |

3 (3.1) |

|

|

Other |

3 (1.3) |

4 (4.1) |

|

|

Mean time (in days) between diagnosis and referral, mean (min – max) |

584 (163 - 1,711) |

497 (198 - 1,771) |

0.800 |

|

Unknown |

1 |

3 |

|

|

Mean time (in days) between referral and first consultation in PC, mean (min – max) |

46 (17 - 80) |

44 (15 - 69) |

0.200 |

|

Unknown |

42 |

2 |

|

|

Death |

|

|

>0.900 |

|

Yes |

182 (81) |

78 (80) |

|

|

No |

44 (19) |

19 (20) |

|

|

Mean time (in days) between referral and patient death, mean (min – max) |

71 (13 - 163) |

84 (43 - 209) |

0.083 |

|

Unknown |

83 |

20 |

|

1n (%); median (IQR); ²Pearson’s chi-squared test; Fisher’s test with simulated p-value; Wilcoxon rank sum test; PCRP = Palliative Care Referral Protocol.

Figure 1. Distribution of PCRP and non-PCRP referrals and frequency

Table 3. Univariate analysis of clinical and sociodemographic predictors associated with referrals to palliative care with and without PCRP

|

Characteristics |

N |

OR1 |

95% CI² |

p - value |

|

Sex |

319 |

|

|

|

|

Female |

|

— |

— |

|

|

Male |

|

1.32 |

0.81- 2.14 |

0.3 |

|

Ethnicity |

312 |

|

|

|

|

White |

|

— |

— |

|

|

Black |

|

1.90 |

0.46 - 12.8 |

0.4 |

|

Brown |

|

1.32 |

0.73 - 2.46 |

0.4 |

|

Marital status |

318 |

|

|

|

|

Single |

|

— |

— |

|

|

Married |

|

1.75 |

0.87 - 3.44 |

0.11 |

|

Consensual marriage |

|

1.38 |

0.52 - 3.79 |

0.5 |

|

Divorced |

|

1.79 |

0.70 - 4.83 |

0.2 |

|

Widow/Widower |

|

1.16 |

0.49 - 2.76 |

0.7 |

|

Religion |

294 |

|

|

|

|

Catholic |

|

— |

— |

|

|

Evangelical |

|

0.96 |

0.54 - 1.73 |

0.9 |

|

Level of education |

313 |

|

|

|

|

< 8 years |

|

— |

— |

|

|

>8 years |

|

1.14 |

0.68 - 1.96 |

0.6 |

|

Professional activity |

302 |

|

|

|

|

Inactive |

|

-- |

-- |

|

|

Metastasis |

311 |

|

|

|

|

No |

|

— |

— |

|

|

Yes |

|

1.00 |

0.51 - 1.87 |

>0.9 |

|

Current treatment |

319 |

|

|

|

|

Palliative care and standard cancer treatment |

|

— |

— |

|

|

Exclusive palliative care |

|

1.81 |

1.10 - 3.00 |

0.020 |

|

Standard cancer treatment |

|

0.83 |

0.28 - 2.60 |

0.7 |

|

ECOG² |

318 |

|

|

|

|

ECOG 0: Normal activity |

|

— |

— |

|

|

ECOG I: Symptoms of the disease, but walks and has a normal day-to-day life |

|

0.56 |

0.11 - 2.50 |

0.5 |

|

ECOG II: Out of bed more than 50% of the time |

|

0.81 |

0.16 - 3.60 |

0.8 |

|

ECOG III: In bed more than 50% of the time, requiring more intensive care |

|

2.58 |

0.48 - 12.0 |

0.2 |

|

ECOG IV: Totally confined to bed or chair |

|

2.56 |

0.50 - 11.2 |

0.2 |

|

KPS³ |

319 |

|

|

|

|

10-20% |

|

— |

— |

|

|

30-50% |

|

0.67 |

0.35 - 1.26 |

0.2 |

|

More than 60% |

|

0.27 |

0.14 - 0.48 |

<0.001 |

|

Performance group |

317 |

|

|

|

|

Green (first consultation should be scheduled within 90 days) |

|

— |

— |

|

|

Yellow (first consultation should be scheduled within 45 days) |

|

2.02 |

1.14 - 3.58 |

0.016 |

|

Red (first consultation should be scheduled within 15 days) |

|

1.53 |

0.83 - 2.88 |

0.2 |

|

Types of cancer according to the protocol |

319 |

|

|

|

|

Breast and gynecological |

|

— |

— |

|

|

Digestive |

|

0.66 |

0.30 - 1.40 |

0.3 |

|

Head and neck/chest |

|

0.20 |

0.09 - 0.40 |

<0.001 |

|

Sarcoma |

|

0.45 |

0.14 - 1.64 |

0.2 |

|

Melanoma |

|

0.21 |

0.03 - 1.22 |

0.070 |

|

Urology |

|

0.85 |

0.32 - 2.34 |

0.7 |

|

Other |

|

0.15 |

0.03 - 0.78 |

0.023 |

|

Death |

319 |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

|

— |

— |

|

|

No |

|

0.98 |

0.54 - 1.81 |

>0.9 |

1OR = odds ratio; ²CI = confidence interval.

Table 4. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of clinical and sociodemographic predictors associated with referrals to palliative care with and without PCRP

|

Characteristics |

OR1 |

95% CI1 |

p - value |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

Female |

— |

— |

|

|

Male |

1.71 |

0.82 - 3.61 |

0.2 |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

White |

— |

— |

|

|

Black |

2.80 |

0.37 - 27.5 |

0.3 |

|

Brown |

1.27 |

0.57 - 2.94 |

0.6 |

|

Yellow |

925.370 |

0.00 - NA |

> 0.9 |

|

Marital status |

|

|

|

|

Single |

— |

— |

|

|

Married |

1.56 |

0.64 - 3.75 |

0.3 |

|

Consensual marriage |

1.50 |

0.42 - 5.57 |

0.5 |

|

Divorced |

2.38 |

0.65 - 9.64 |

0.2 |

|

Widow/Widower |

1.53 |

0.47 - 5.01 |

0.5 |

|

Religion |

|

|

|

|

Catholic |

— |

— |

|

|

Evangelical |

0.95 |

0.46 - 2.02 |

0.9 |

|

Other |

0.40 |

0.11 - 1.58 |

0.2 |

|

Professional activity |

|

|

|

|

Inactive |

— |

— |

|

|

Distant metastasis |

|

|

|

|

No |

— |

— |

|

|

Yes |

1.00 |

0.43 - 2.22 |

>0.9 |

|

Current treatment |

|

|

|

|

Palliative care and standard cancer treatment |

— |

— |

|

|

Exclusive palliative care |

0.80 |

0.38 - 1.68 |

0.6 |

|

Standard oncological treatment |

0.99 |

0.20 - 6.67 |

> 0.9 |

|

Performance Status Scale (ECOG) |

|

|

|

|

ECOG 0: Normal activity |

— |

— |

|

|

ECOG I: Symptoms of the disease, but walks and has a normal day-to-day life |

0.30 |

0.04 - 1.93 |

0.6 |

|

ECOG II: Out of bed more than 50% of the time |

0.55 |

0.07 - 3.77 |

0.5 |

|

ECOG III: In bed more than 50% of the time, requiring more intensive care |

2.08 |

0.20 - 20.0 |

0.5 |

|

ECOG IV: Totally confined to bed or chair |

0.88 |

0.05 - 13.7 |

>0.9 |

|

Performance Status Scale - KPS |

|

|

|

|

10-20% |

— |

— |

|

|

30-50% |

0.50 |

0.07 - 3.43 |

0.5 |

|

More than 60% |

0.54 |

0.05 - 4.84 |

0.6 |

|

Performance group |

|

|

|

|

Green (first consultation should be scheduled within 90 days) |

— |

— |

|

|

Yellow (first consultation should be scheduled within 45 days) |

2.71 |

1.30 - 5.80 |

0.009 |

|

Red (first consultation should be scheduled within 15 days) |

2.13 |

0.91 - 5.13 |

0.086 |

|

Type of cancer according to the Protocol |

|

|

|

|

Breast and gynecological |

— |

— |

|

|

Digestive |

0.59 |

0.22 - 1.51 |

0.3 |

|

Head and neck/chest |

0.21 |

0.08 - 0.52 |

0.001 |

|

Sarcoma |

0.26 |

0.06 - 1.11 |

0.061 |

|

Melanoma |

0.14 |

0.02 - 0.99 |

0.044 |

|

Urology |

0.89 |

0.27 - 3.00 |

0.8 |

|

Other |

0.20 |

0.02 - 2.16 |

0.2 |

|

Death |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

— |

— |

|

|

No |

2.15 |

0.93 - 5.29 |

0.083 |

|

Education |

|

|

|

|

< 8 years |

— |

— |

|

|

> 8 years |

1.57 |

0.76 - 3.35 |

0.2 |

|

|

|||

1OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

![]()

Este é um artigo publicado em acesso aberto (Open Access) sob a licença Creative Commons Attribution, que permite uso, distribuição e reprodução em qualquer meio, sem restrições, desde que o trabalho original seja corretamente citado.