ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Management and Prognosis of Head and Neck Cancer Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Manejo e Prognóstico de Pacientes com Câncer de Cabeça e Pescoço durante a Pandemia de Covid-19

Manejo y Pronóstico de Pacientes con Cáncer de Cabeza y Cuello durante la Pandemia de COVID-19

https://doi.org/10.32635/2176-9745.RBC.2025v71n2.5046

Giuliano Lozer Bruneli1; Priscila Marinho de Abreu2; Jhully Oliveira Ferreira3; Camila Batista Daniel4; Jéssica Graça Sant'Anna5; Roberta Ferreira Ventura Mendes6; Brena Ramos Athaydes7; Mariane Vedovatti Monfardini Sagrillo8; José Roberto Vasconcelos de Podestá9; Marco Homero de Sá Santos10; Jeferson Lenzi11; Evandro Duccini de Souza12; Ricardo Mai Rocha13; Regina de Pinho Keller14; Liliana Cruz Spano15; Sandra Ventorin von Zeidler16

1Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo (Ufes), Centro de Ciências da Saúde (CCS), Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Odontológicas. Vitória (ES), Brasil. E-mail: giulianomestradoufes@gmail.com. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2277-5854

2Ufes, CCS, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Odontológicas e Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biotecnologia. Vitória (ES), Brasil. E-mail: priscilamarinho84@gmail.com. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6453-7171

3Ufes, CCS, Departamento de Patologia. Vitória (ES), Brasil. E-mail: jhullyoliveira09@hotmail.com. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8281-2173

4-6,8Ufes, CCS, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biotecnologia. Vitória (ES), Brasil. E-mails: batistad.camila@gmail.com; jessica.gs2@hotmail.com; robertaventuram@gmail.com; marianemonfardini@yahoo.com.br. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3992-5986; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9759-2978; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2284-5683; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2075-1579

7Ufes, CCS, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biotecnologia e Departamento de Patologia. Vitória (ES), Brasil. E-mail: brena.ramos@hotmail.com. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8954-771X

9,11,12Hospital Santa Rita de Cássia, Serviço de Cirurgia de Cabeça e Pescoço, Programa de Prevenção e Detecção Precoce do Câncer Bucal. Vitória (ES), Brasil. E-mails: podestajr@gmail.com; jefersonlenei@hotmail.com; evandroduccimi@terra.com.br. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6995-955X; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9407-0784; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4272-6091

10Hospital Universitário Cassiano Antônio Moraes – EBSERH. Vitória (ES), Brasil. E-mail: marcohomero.santos@gmail.com. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2156-3545

13Hospital Santa Rita de Cássia, Serviço de Cirurgia de Cabeça e Pescoço, Programa de Prevenção e Detecção Precoce do Câncer Bucal. Hospital Universitário Cassiano Antônio Moraes – EBSERH. Vitória (ES), Brasil. E-mail: ricardomai@gmail.com. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5283-6860

14Ufes, Departamento de Engenharia Ambiental. Vitória (ES), Brasil. E-mail: kellygtr@gmail.com. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9163-0715

15Ufes, CCS, Departamento de Patologia, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Infectologia. Vitória (ES), Brasil. E-mail: liliana.spano@ufes.br. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6205-6988

16Ufes, CCS, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Odontológicas, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biotecnologia e Departamento de Patologia. Vitória (ES), Brasil. E-mail: sandra.zeidler@ufes.br. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8897-5747

Corresponding author: Sandra Ventorin von Zeidler. Ufes, CCS, Departamento de Patologia. Av. Marechal Campos, 1468 – Maruípe. Vitória (ES), Brasil. CEP 29040-090. E-mail: sandra.zeidler@ufes.br

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic raised the necessity to implement measures for managing patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Objective: To evaluate the measures adopted by an oncological hub during the COVID-19 pandemic and investigate whether the SARS-CoV-2 infection and viral load changed the outcomes of head and neck cancer patients. Method: Patients were tested for SARS-CoV-2 using real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and rapid COVID-19 antigen testing before surgery between October 2020 and November 2021. Clinical outcomes were compared by the presence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, considering prognostic factors for HNSCC patients, such as preexisting comorbidities and tumor staging. Results: Of the 194 patients recruited, 99 cases confirmed diagnoses of HNSCC and underwent surgical treatment. The most frequent comorbidities were arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus. The oral cavity and larynx were the most affected anatomical sites, 51% and 33%, respectively. A total of 61.6% of the cases were classified as T3/T4 and 53.4% did not have lymph node involvement. Presence of comorbidities and lymph node metastasis were associated with reduced survival. Of the 99 cases confirmed, 8.1% (8/99) were infected with SARS-CoV-2, but no differences in overall survival according to SARS-CoV-2 infection (p = 0.086) were noticed and the viral load was not associated with vital status (p = 0.456). Conclusion: The presence of SARS-CoV-2 infection did not influence overall survival in head and neck SCC patients. This is the first study to describe these findings in an oncological care center in the State of Espírito Santo, Brazil.

Key words: COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; Head and Neck Neoplasms; Carcinoma, Squamous Cell; Survival.

RESUMO

Introdução: A pandemia de covid-19 trouxe a necessidade de implementar medidas para o manejo de pacientes com carcinoma espinocelular (CEC) de cabeça e pescoço. Objetivo: Avaliar as medidas adotadas por um polo oncológico durante a pandemia de covid-19 e investigar se a infecção por SARS-CoV-2 e a carga viral alteram os desfechos de pacientes com câncer de cabeça e pescoço. Método: Os pacientes foram testados para SARS-CoV-2 usando reação em cadeia da polimerase de transcrição reversa quantitativa em tempo real e teste rápido de antígeno covid-19 antes da cirurgia entre outubro de 2020 e novembro de 2021. Os desfechos clínicos foram comparados pela presença de infecção por SARS-CoV-2, considerando fatores prognósticos para pacientes com CEC de cabeça e pescoço, como comorbidades preexistentes e estadiamento tumoral. Resultados: Dos 194 pacientes recrutados, 99 casos confirmaram o diagnóstico de CEC de cabeça e pescoço e foram submetidos a tratamento cirúrgico. As comorbidades mais frequentes foram hipertensão arterial e diabetes mellitus. A cavidade oral e a laringe foram os sítios anatômicos mais afetados, com 51% e 33%, respectivamente. Um total de 61,6% dos casos foi classificado como T3/T4 e 53,4% não apresentaram comprometimento linfonodal. A presença de comorbidades e metástase linfonodal foram associadas à redução da sobrevida. Dos 99 pacientes, 8,1% (8/99) estavam infectados pelo SARS-CoV-2, mas não foi observada diferença na sobrevida global de acordo com a infecção pelo SARS-CoV-2 (p = 0,086) e a carga viral não foi associada ao estado vital (p = 0,456). Conclusão: A presença de infecção pelo SARS-CoV-2 não influenciou a sobrevida global em pacientes com CEC de cabeça e pescoço. Este é o primeiro estudo a descrever esses achados em um centro de atendimento oncológico no Estado do Espírito Santo, Brasil.

Palavras-chave: COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; Neoplasias de Cabeça e Pescoço; Carcinoma de Células Escamosas; Sobrevida.

RESUMEN

Introducción: La pandemia de COVID-19 trajo consigo la necesidad de implementar medidas para el manejo de pacientes con carcinoma de células escamosas (CCE) de cabeza y cuello. Objetivo: Evaluar las medidas adoptadas para un centro oncológico durante la pandemia de COVID-19 e investigar si la infección por SARS-CoV-2 y la carga viral cambian los resultados de los pacientes con cáncer de cabeza y cuello. Método: Se realizó una prueba de detección de SARS-CoV-2 a los pacientes mediante reacción en cadena de la polimerasa con transcripción inversa cuantitativa en tiempo real y prueba rápida de antígeno COVID-19 antes de la cirugía entre octubre de 2020 y noviembre de 2021. Los resultados clínicos se compararon según la presencia de infección por SARS-CoV-2, considerando factores pronósticos para pacientes con CCE de cabeza y cuello, como comorbilidades preexistentes y estadificación tumoral. Resultados: De 194 pacientes reclutados, 99 casos confirmaron diagnósticos de CCE de cabeza y cuello y se sometieron a tratamiento quirúrgico. Las comorbilidades más frecuentes fueron hipertensión arterial y diabetes mellitus. La cavidad oral y la laringe fueron los sitios anatómicos más afectados, con el 51% y 33%, respectivamente. Un total de 61,6% de los casos fue clasificado como T3/T4 y el 53,4% no presentó afectación ganglionar. La presencia de comorbilidades y metástasis ganglionares se asoció con una supervivencia reducida. De 99 pacientes, el 8,1% (8/99) estaba infectado con SARS-CoV-2, pero no se observa la diferencia en la supervivencia general según la infección por SARS-CoV-2 (p = 0,086) y la carga viral no se asoció con el estado vital (p = 0,456). Conclusión: La presencia de infección por SARS-CoV-2 no influyó en la supervivencia general en pacientes con CCE de cabeza y cuello. Este es el primer estudio que describe estos hallazgos en un centro de atención oncológica en el estado de Espírito Santo, Brasil.

Palabras clave: COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; Neoplasias de Cabeza y Cuello; Carcinoma de Células Escamosas; Sobrevida.

INTRODUCTION

Since March 11, 2020, when the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 pandemic, most national authorities have imposed restrictive measures to contain the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), thus preventing the collapse of national health care systems1. In this way, new health care pathways were defined, and a reduction in elective surgical volume was adopted as one of the measures to protect surgical teams and preserve important health care resources.

Older adults and patients with noncommunicable diseases, including cancer, were at increased risk of severe complications and poor outcomes from COVID-192,3. In this regard, cancer care was immediately established as a health priority. By temporarily delaying the service availability to cancer patients needing non deferrable life-saving treatments, most of them non elective surgeries, national and international surgical associations promptly drew up guidelines for adapting the management of cancer patients in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic4,5.

The rapid spread of the novel coronavirus through respiratory droplets, the high viral load, and their regular exposure to aerosol-generating therapeutic procedures make health professionals who come in close contact with the upper aerodigestive tract during diagnosis, as head and neck surgeons and their coworkers, particularly at risk of infection, requiring even safer protocols to continue their activities4.

In addition, the poor clinical outcomes of patients with head and neck cancer who developed COVID-19 during the perioperative period have greatly impacted surgical practice and decision-making in this cancer typing6,7. Hence, the reorganization of oncological care had an important role in ensuring adequate treatment after several studies showed high mortality rates in cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, ranging from 11.4 to 28.6%, which was notably higher than the 2.3% rate reported for the general population infected with the novel coronavirus8,9.

Therefore, the workflows of the Head and Neck Surgery Division for published national and international protocols were adapted to reduce the spread of the new coronavirus and mitigate the effects of COVID-19 on patients with head and neck cancer, while still ensuring adequate oncological care. The present article reports the surgical treatment of head and neck cancer patients at the Head and Neck Division of Hospital Santa Rita de Cássia – Associação Feminina de Educação e Combate ao Câncer (AFECC), a regional reference for the treatment of cancer patients in Espírito Santo, located at Brazil southeast, with the objective of evaluating the measures adopted for this oncological hub during the COVID-19 pandemic and investigate whether the SARS-CoV-2 infection and the viral load change the outcomes of head and neck cancer patients.

METHOD

Longitudinal cohort study enrolling all consecutive eligible patients who underwent exclusive surgical procedures for the treatment or diagnosis of head and neck malignancies at the Head and Neck Surgery Service of Hospital Santa Rita de Cássia, AFECC, Espírito Santo, Brazil. No baseline concomitant treatments were performed. The patients were recruited between October 2020 and November 2021 and were followed up for 20 months at the most.

The Ethics Committee of the “Centro de Ciências da Saúde da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo (UFES)” approved the study (CAAE (submission for ethical review): 61413216.7.0000.5060, report number 4.251.850) in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki “Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects” and with Directive 466, December 12, 2012 of the National Health Council (CNS)10. The patients who agreed to participate were informed about all the procedures and the purpose of the study and eventually signed the Informed Consent Form (ICF). All the participants were older than 18 years.

The beginning of this period was a critical time in terms of rearrangement and monitoring of the health care system for the management of cancer patients4, in particular, for whom surgery would be often classified as urgent even under the then restrictive policy. Thus, a set of measures was adopted to reduce the viral exposure of health care workers and minimize the complications of cancer treatment in patients with COVID-19.

Before hospitalization, all head and neck cancer patients underwent general telephone triage and evaluation of health status, presence of the most frequent fever symptoms, fatigue, possible symptoms, and dyspnea. Only asymptomatic patients were scheduled for surgery, while symptomatic patients were instructed to reschedule surgery 15 days after cessation of symptoms. Surgical masks were mandatory upon entry, and body temperature was measured via infrared thermometers.

As a preoperative assessment, all the patients underwent blood analysis and chest X-ray per the protocol. From October 1, 2020 onward, a nasopharyngeal swab was collected before accessing the operating room, and a rapid COVID-19 antigen test (Biocredit COVID-19 Antigen, RapiGEN Inc., Republic of Korea) was performed in all new patients with head and neck tumors. The intervention according to the hospital protocol was to include the PCR test as a measure to improve the safety of health professionals and patients.

In 2020, two head and neck surgeons of the team were diagnosed with COVID-19. In 2021, all team members received the anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and only two presented flu-like symptoms, but the RT-PCR test was negative. Hospital Santa Rita de Cássia is a regional oncological hub, and many patients come from the countryside. For those who could attend the hospital 1-2 days before the surgery, the PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 was performed to obtain the result before admission and the patients who could not, underwent the PCR-based test in parallel to the rapid COVID-19 antigen test. If any of the diagnostic tests were positive, the procedure was postponed until the patient’s clinical condition improved and the test became negative. The results of the SARS-CoV-2 detection analysis were immediately sent to the medical team, following the recommendations of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention11. Some patients who were unable to undergo the tests mentioned above were evaluated using serology for the detection of the antibodies anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgM.

All the patients were previously tested for SARS-CoV-2 using RT-qPCR and a rapid antigen test (Biocredit COVID-19 Antigen, RapiGEN Inc., Republic of Korea). Respiratory samples were collected using rayon-tipped swabs (two from the nasopharynx and one from the oropharynx) and stored in viral transport medium at 4°C. Samples were processed within 72 hours, with RNA extraction performed using the Pure Link™ Viral RNA/DNA Mini Kit (Invitrogen). Viral detection was conducted by RT-qPCR (GoTaq® Probe 1-Step, Promega) with primers and hydrolysis probes targeting the N1 and N2 genes, following CDC recommendations. The virus was considered detectable if the cycle threshold (CT) was <40, undetectable if CT was >40, and inconclusive if only one gene had a CT <40. The assay was conducted using an Applied Biosystems 7500 real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Specificity and sensitivity of the rapid COVID-19 antigen tests and the RT-qPCR tests were calculated. Sensitivity was defined as the probability of a positive antigen test when SARS-CoV-2 was present (RT-qPCR positive), while specificity was the probability of a negative antigen test when SARS-CoV-2 was absent (RT-qPCR negative). The positive predictive value represented the likelihood that a positive antigen test indicated a true infection, whereas the negative predictive value reflected the likelihood that a negative antigen test indicated the absence of infection.

For viral quantification, a commercial positive control (TDI) was serially diluted from 2.0×10⁰ to 2.0×10⁵ copies/μL, generating a six-point standard curve in triplicate with an efficiency of 90–110%. SARS-CoV-2 viral load was determined in duplicate by comparison with the standard curve, using the same primers and N1 probe as those used for detection. Reactions were performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Foster City, CA, USA).

The qualitative detection of IgG and IgM antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in human serum was carried out at the Tommasi Laboratory using CHEMIFEX automated assay, the two-step chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay technology, at ARCHITECT ci4100 (Abbott Laboratories Diagnostics Division, IL, USA), as well as SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgM Reagent Kits.

Patient characteristics (sex, age at diagnosis, comorbidities), tumor features (primary tumor subsite, pathological type, TNM12 clinical stage 8th edition, tobacco and alcohol exposure, and primary treatment (treatment modality, date of first treatment), and date of diagnosis were obtained from the medical records.

Considering that there is no uniformity in the occurrence of COVID-19 in the population and that aggravation and death are especially related to sociodemographic characteristics and preexisting comorbidities, the characterization of risk according to the National Plan for the Operationalization of Vaccination against COVID-1913 was adopted. Thus, an active search of medical records for the following comorbidities have been conducted: chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, severe arterial hypertension, severe chronic lung diseases, sickle cell anemia, and morbid obesity (BMI≥40).

To avoid bias in the survival analyses, since tumors in the head and neck region have different prognosis in anatomical sites and histological types, thyroid and salivary gland tumors were excluded from this analysis. Thus, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) was classified according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd edition (ICD-O-3)14 and included cancers of the oral cavity (C00.3-C00. 9; C01–C06), oropharynx (C09–C10), hypopharynx (C13), larynx (C32), and nasopharynx (C11). All tumors were confirmed by microscopy and restricted to squamous cell carcinoma (morphological international codes 8070, 8071, 8072, 8076, 8051, and 8083). After this selection, this patient group was followed up for 20 months or until death.

The variables selected were: sex (female or male); age (grouped as less than or equal to 60 years old, and over 60 years old); comorbidities (yes or no); anatomical tumor site (oral cavity/lip, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, and nasopharynx); tumor size, grouped into early tumors (T1/T2) and advanced tumors (T3/T4); nodal metastasis, grouped into the absence of metastasis (N0) and presence of metastasis (N+); distant metastasis (presence or absence); alcohol consumption (yes – current or former; and no); tobacco consumption (yes – current or former; and no); types of comorbidities (arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, hepatic cirrhosis, and no comorbidities); real-time PCR results (positive or negative); clinical outcome (death or alive); and viral load (the only quantitative variable).

The chi-squared test and Fisher's exact probability test were used to evaluate the associations among the variables comorbidities, anatomic site, age, tumor size (T), nodal metastasis (N), and distant metastasis (M) in positive and negative groups for SARS-CoV-2 by the real-time RT-qPCR test. Missing data were excluded from the analysis. Overall survival (OS) was estimated and compared using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank tests, respectively. For OS analysis, death data versus total survival duration were considered.

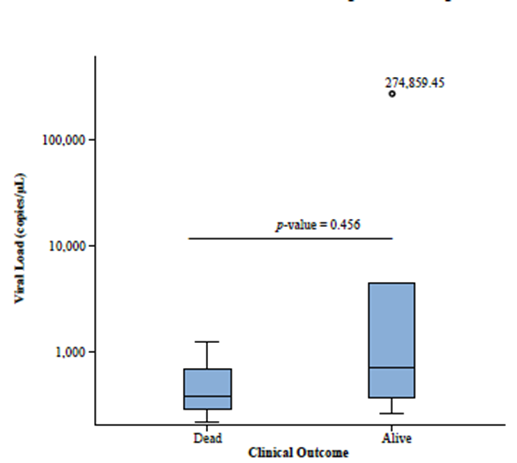

All cases where the event of interest occurred (death) were considered not censored for OS calculation. The cases where the event did not occur until the last follow-up data were censored. Patients lost to follow-up were included in the analysis performed and contributed to the time they were being followed up. The Mann-Whitney U test was run to compare the viral load means of positive patients for SARS-CoV-2 with different clinical outcomes (dead or alive). Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS15 software version 23.0 for Windows (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Chicago, USA). The level of statistical significance was p < 0.05. The STROBE cohort checklist was adopted16.

RESULTS

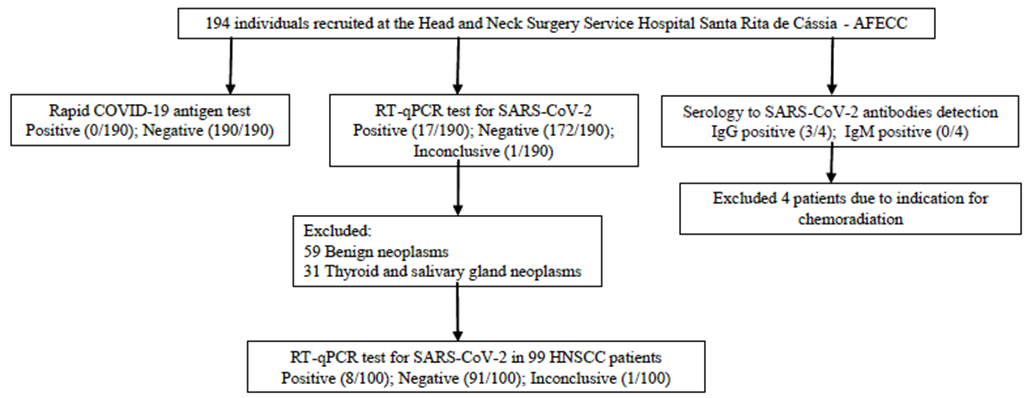

Over the period examined, a total of 194 patients were admitted to the Head and Neck Service (median age 57.5 years, [range: 18-97], 67.5% men) being 135 patients included in the study after the beginning of anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in Brazil. Among these patients, 190 were tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection by applying the COVID-19 antigen test and the RT-qPCR test, and four were tested by serological testing. Figure 1 details the COVID-19 results for each technique.

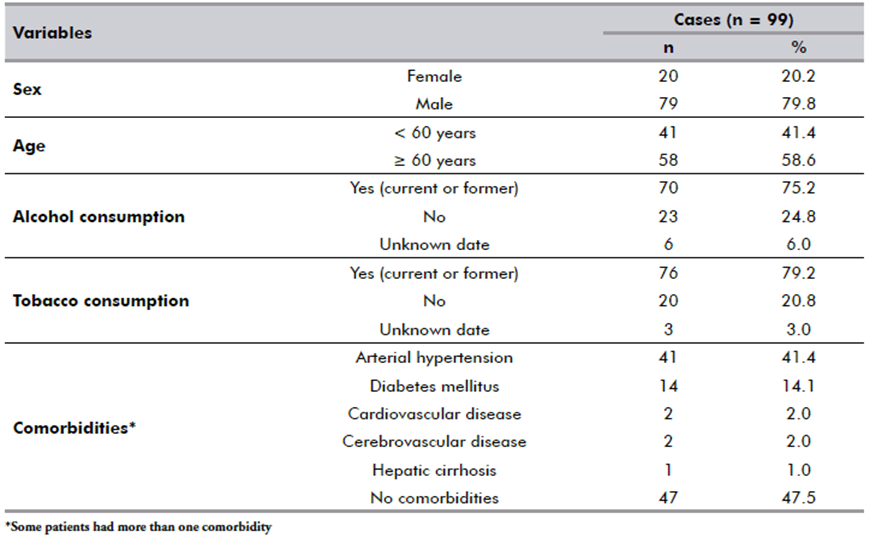

Among the recruited patients, 99 were diagnosed with HNSCC and underwent surgery. Patients with benign neoplasms and thyroid or salivary gland neoplasms were excluded from the prognostic analysis, as well as those patients who underwent chemoradiation (Figure 1). HNSCC patients were mostly males (79.8%), smokers and alcohol users (79.2% and 75.2%, respectively). Arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus were the most frequent comorbidities (41.4% and 14.1%, respectively), and some patients had more than one comorbidity. No registers of COVID-19 were found in the medical records during the 20-month follow-up period. These data are summarized in Table 1.

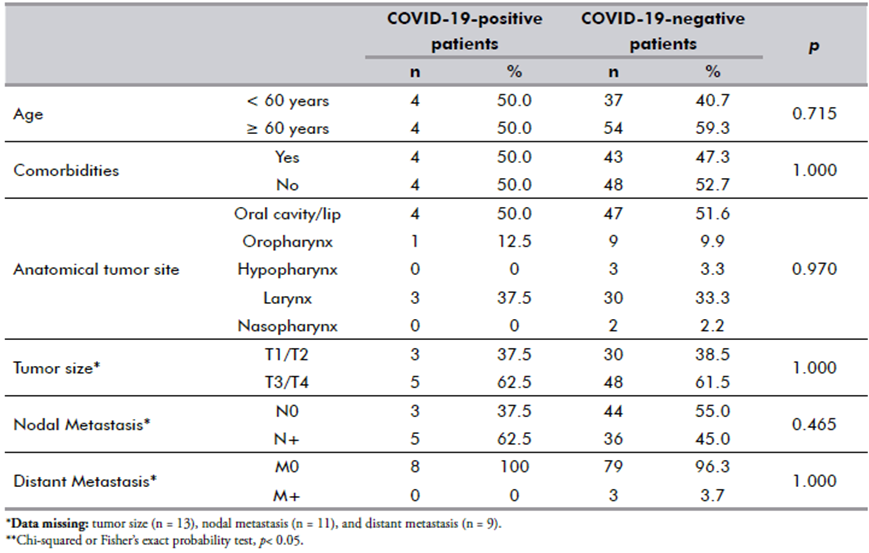

The most frequently affected anatomical site were oral cavity (51.5%), and larynx (33.3%). Most patients had advanced disease, 53 (61.6%) classified as T3/T4, while 47 (53.4%) had no lymph node involvement (N0) and 3 (3.3%) had distant metastasis (Table 2).

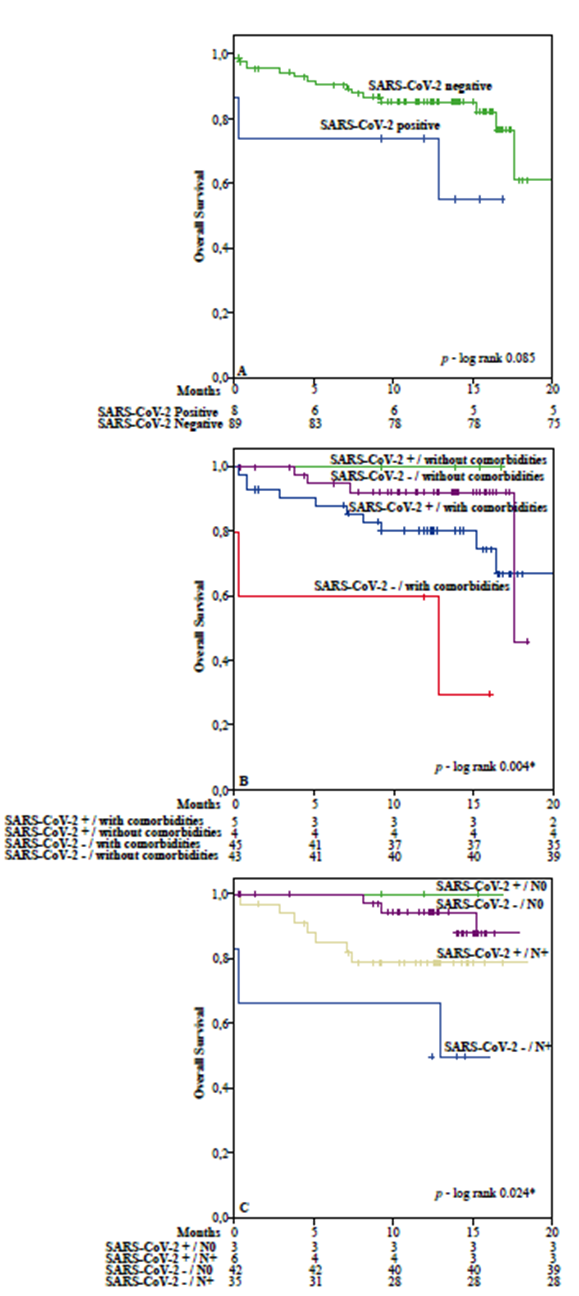

Eight HNSCC patients tested positive for COVID-19 but had no symptoms when screened. No association between COVID-19 status and clinicopathologic features (Table 2) or overall survival (Figure 2A) was found. Among the patients analyzed (1/194), only one died in the immediate postoperative period, a patient who took the rapid and PCR tests in parallel, was tested negative for the COVID-19 antigen test but positive for the RT-qPCR test afterwards.

As shown in Figure 2B, patients with any comorbidity had a shorter overall survival than those without comorbidities (mean: 15.8 vs. 17.1 months; p = 0.004). Patients with baseline lymph node metastasis and SARS-CoV-2 infection had worse OS than those with neither COVID-19 nor lymph node metastasis (p = 0.024) (Figure 2C).

The sensitivity and specificity of the 99 samples included in this analysis were negative by rapid COVID-19 antigen test. Concomitantly, there were eight false negatives and zero false positives, eventually achieving a specificity of 100% and a negative predictive value of 92%. However, sensitivity and positive predictive values were calculated at 0%.

The relationship between viral load and clinical outcome based on vital status during the 20 months after treatment was assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test. There was no association between the analyzed variables (p = 0.456), which shows that viral load did not differ between patients who died and those who were alive until the end of follow-up (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

HNSCC patients comprise a highly vulnerable group who were at increased risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 and of experiencing more serious disease outcomes due to their immunocompromised status and the transmission mechanism of the virus17. Thus, several changes have been made in cancer management practice across the world to minimize the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prognosis of HNSCC patients. Measures adapted by international and national guidelines to reduce the spread of the new coronavirus among HNSCC patients treated at a head and neck surgery service from a referral oncology service center in Brazil have been described herein.

The management of HNSCC was significantly affected during the COVID-19 pandemic, both due to high-risk aerosol-generating procedures and limited health care capacity and resources18. Notably, HNSCC patients have been compelled to attend frequent visits to the hospital, resulting in a greater exposure and likelihood of developing the disease than the general population19,20. Despite these factors, the delay in the diagnosis and treatment of HNSCC could lead to an increase in mortality as well as the risk of recurrence21. Therefore, measures to maintain the oncological routine were urgent, especially in Brazil, where most cases of HNSCC are diagnosed at late stages22.

The workflows were adapted at the hospital’s head and neck service to the screening protocols previously proposed23,24 to include those patients who live far from the cancer center and cannot attend the hospital to test for SARS-CoV-2 before surgery, which is a common scenario for oncology centers in Brazil. The results showed that the set of measures implemented was effective to prevent unfavorable outcomes for HNSCC patients since only one SARS-CoV-2-positive patient died (1/194).

The use of the rapid test helped to screen patients and facilitated the access to the head and neck surgery service with reduced waiting time. However, as the rapid test had greater specificity and low sensitivity, it is possible that patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 have not been detected by the test. This occurred with the eight patients who tested negative at screening, but SARS-CoV-2 was still detected by RT-qPCR, which is the globally accepted gold standard for virus detection25. Therefore, the inclusion of this test improved the safety of health professionals and patients, since patients who managed to perform the RT-qPCR previously and were positive, remained in quarantine for at least 15 days before surgery.

The impacts of SARS-CoV-2 infection, comorbidities, and clinical tumor stage on the outcome of HNSCC have been analyzed. No difference of OS due to SARS-CoV-2 infection was noticed, though patients with lymph node metastasis had worse OS regardless of the COVID-19 status. Lymph node metastasis is the most important prognostic factor in HNSC26, but its impact on the prognosis of cancer patients with COVID-19 has not been described before.

The long-term OS of cancer patients who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 was lower than that of those who are not27,28, but for HNSCC, the evidence is still limited. In a study by Venkatasai,18 the 1-year progression-free survival and overall survival pre-COVID-19 were not different from those in the COVID-19 era, but the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on HNSCC patients was not assessed.

The present study had a 20 month follow-up period and it was the first to explore the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the long-term survival of HNSCC patients. In despite of concerns about the early phase of the pandemic focused on postoperative complications caused by COVID-19, a recently published OnCovid study29 demonstrated that the sequelae of COVID-19 may adversely affect the long-term survival of cancer patients30.

The present results indicate that HNSCC patients with one or more comorbidities had worst prognosis. In the study by Hussain31, the most severe cases of SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals occurred in older adults or patients with underlying comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic lung disease, chronic renal disease, hypertension, and cancer. These findings were consistent with previous studies32,33. When compared to the general population, HNSCC patients present a higher comorbidity rate, which may be attributed to their advanced age and chronic exposure to risk factors that are also associated with the pathogenesis of several diseases, as alcohol and tobacco consumption34.

One of the study limitations was the short follow-up time for the survival analysis (median 20 months), as the median follow-up for HNSCC patients is five years. Even so, it is a valuable assessment of the measures taken during the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure that HNSCC patients received adequate treatment and to determine the long-term impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on their prognosis, further to the regional relevance since it is the only study to describe these changes in an oncological care center in the state of Espírito Santo.

The present investigation was important to improve the management of cancer patients in a severe pandemic scenario. The results may help when new endemic diseases appear and encourage future research to reduce the time and improve the efficiency of diagnostic tests.

CONCLUSION

The set of measures implemented at the Head and Neck Service of Hospital Santa Rita de Cássia has effectively mitigated the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on HNSCC patients and on the team involved in their treatment. The current findings indicate that SARS-CoV-2 did not affect OS of the hospital team, and comorbidities and lymph node metastasis were associated with reduced survival.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

To Hospital Santa Rita de Cássia, AFECC, and the Head and Neck Surgery team for supporting the development of this research and patient recruitment. Tommasi Laboratory – Dr Jorge Luiz Joaquim Terrão and the Laboratório de Gastroenterite e Virologia of Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo for their support with the techniques used in this study.

CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors contributed substantially to the study design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, wording and critical review. They approved the final version to be published.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

There is no conflict of interests to declare.

FUNDING SOURCES

This study was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Espírito Santo (FAPES, grant number 2020-K31T3) and partially supported by Coordination of Higher Education and Graduate Training (CAPES) Grant 001.

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Responding to community spread of COVID-19: interim guidance, 7 March 2020 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [citado em 2025 Mar 31]. Disponível em: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/331421

2. Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

3. Sharma A, Crosby DL. Special considerations for elderly patients with head and neck cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Head Neck. 2020;42(6):1147-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.14639/0392-100X-N0941

4. Givi B, Schiff BA, Chinn SB, et al. Safety recommendations for evaluation and surgery of the head and neck during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(6):579-84. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0780

5. Mehanna H, Gillison M, Lee AWM, et al. Adapting head and neck cancer management in the time of COVID-19. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;107(4):628-30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.04.017

6. Kowalski LP, Sanabria A, Ridge JA, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: effects and evidence-based recommendations for otolaryngology and head and neck surgery practice. Head Neck. 2020;42(6):1259-67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26164

7. Topf MC, Shenson JA, Holsinger FC, et al. Framework for prioritizing head and neck surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Head Neck. 2020;42(6):1159-67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26184

8. Zhang L, Zhu F, Xie L, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19-infected cancer patients: a retrospective case study in three hospitals within Wuhan, China. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(7):894-901. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.296

9. Song K, Gong H, Xu B, et al. Association between recent oncologic treatment and mortality among patients with carcinoma who are hospitalized with COVID‐19: a multicenter study. Cancer. 2020;127(3):437-48. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33240

10. Conselho Nacional de Saúde (BR). Resolução n° 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. Aprova as diretrizes e normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF. 2013 jun 13; Seção I:59.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Real-Time RT-PCR Diagnostic Panel. Revision 5. Atlanta: CDC; 2020.

12. Huang SH, O’Sullivan B. Overview of the 8th edition TNM Classification for head and neck cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18(40). doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-017-0484-y

13. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Plano nacional de operacionalização da Vacinação contra a Covid-19 [Internet]. 2. ed. Brasília, DF: MS; 2022. [Cited 2024 nov 25]. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/plano_nacional_operacionalizacao_vacinacao_covid19.pdf

14. Fritz A, Percy C, Jack A, et al. World Health Organization: international classification of diseases for oncology. 3. ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Cited 2024 nov 25]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2000/9241545348_eng.pdf

15. SPSS®: Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) [Internet]. Versão 23.0. [Nova York]. International Business Machines Corporation. [acesso 2024 nov 9]. Disponível em: https://www.ibm.com/br-pt/spss?utm_content=SRCWW&p1=Search&p4=43700077515785492&p5=p&gclid=CjwKCAjwgZCoBhBnEiwAz35Rwiltb7s14pOSLocnooMOQh9qAL59IHVc9WP4ixhNTVMjenRp3-aEgxoCubsQAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds

16. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

17. Dermody SM, Shuman AG. Psychosocial implications of COVID-19 on head and neck cancer. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(2):1062-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29020090

18. Venkatasai J, John C, Kondavetti SS, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patterns of care and outcome of head and neck cancer: real-world experience from a tertiary care cancer center in India. JCO Glob Oncol. 2022;8:1-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1200/go.21.00339

19. Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335-7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30096-6

20. Aboueshia M, Hussein MH, Attia AS, et al. Cancer and COVID-19: analysis of patient outcomes. Futur Oncol. 2021;17(26):3499-510. doi: https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2021-0121

21. Adham M, Anam K, Reksodiputro LA. Treatment prioritization and risk stratification of head and neck cancer during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Med J Malaysia [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 nov 24];77(1):53-9. Available from: https://www.e-mjm.org/2022/v77n1/head-and-neck-cancer.pdf

22. Nancy Chow KFD, Gierke R, Hall A, et al. Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708-20. doi: https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e2

23. Day AT, Sher DJ, Lee RC, et al. Head and neck oncology during the COVID-19 pandemic: reconsidering traditional treatment paradigms in light of new surgical and other multilevel risks. Oral Oncol. 2020;105(March):104684. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104684

24. Chaves ALF, Castro AF, Marta GN, et al. Emergency changes in international guidelines on treatment for head and neck cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oral Oncol. 2020;107:104734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104734

25. Dutta D, Naiyer S, Mansuri S, et al. COVID-19 diagnosis: a comprehensive review of the RT-qPCR method for detection of SARS-CoV-2. Diagnostics. 2022;12(6):1-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12061503

26. Sano D, Yabuki K, Takahashi H, et al. Lymph node ratio as a prognostic factor for survival in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2018;45(4):846-53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2017.11.015

27. Chai C, Feng X, Lu M, et al. One-year mortality and consequences of COVID-19 in cancer patients: a cohort study. IUBMB Life. 2021;73(10):1244-56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/iub.2536

28. Trifanescu OG, Gales L, Bacinschi X, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on treatment and oncologic outcomes for cancer patients in romania. In Vivo (Brooklyn). 2022;36(2):934-41. doi: https://doi.org/10.21873/invivo.12783

29. Imperial College London. OnCOVID: impact of COVID-19 in cancer patients [Internet]. London: NIHR Imperial BRC; 2020. [cited 2025 fev 18]. Available from: https://imperialbrc.nihr.ac.uk/research/infection/covid-19/covid-19-ongoing-studies/oncovid/

30. Pinato DJ, Tabernero J, Bower M, et al. Prevalence and impact of COVID-19 sequelae on treatment and survival of patients with cancer who recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection: evidence from the OnCovid retrospective, multicentre registry study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(12):1669-80. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(21)00573-8

31. Hussain A, Bhowmik B, Vale Moreira NC. COVID-19 and diabetes: knowledge in progress. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;162:108142. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108142

32. Ejaz H, Alsrhani A, Zafar A, et al. COVID-19 and comorbidities: deleterious impact on infected patients. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(12):1833-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2020.07.014

33. Gallo Marin B, Aghagoli G, Lavine K, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 severity: a literature review. Rev Med Virol. 2021;31(1):1-10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.2146

34. Schimansky S, Lang S, Beynon R, et al. Association between comorbidity and survival in head and neck cancer: results from head and neck 5000. Head Neck. 2019;41(4):1053-62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25543

Recebido em 10/12/2024

Aprovado em 12/2/2025

Scientific-editor: Anke Bergmann. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1972-8777

Figure 1. Prognostic impact of SARS-CoV-2 on HNSCC patients

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 2. SARS-CoV-2 infection and its associations with clinicopathological and sociodemographic features

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier estimates of 20-month overall survival (OS) in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. (A) OS according to real-time PCR results; (B) OS according to COVID-19 plus different comorbidities; and (C) OS according to COVID-19 plus nodal metastasis. Dashes on the curve represent censored data

Figure 3. Box-plots of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients in different clinical outcomes. The top of the box represents the 75th percentile, the bottom of the box represents the 25th percentile, and the line in the middle represents the 50th percentile. Comparison of viral load in different clinical outcomes was performed by the Mann-Whitney U test

![]()

Este é um artigo publicado em acesso aberto (Open Access) sob a licença Creative Commons Attribution, que permite uso, distribuição e reprodução em qualquer meio, sem restrições, desde que o trabalho original seja corretamente citado.