ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Paclitaxel Modula a Proliferação e a Diferenciação de Células THP-1 Expostas ao Vírus SARS-CoV-2 Inativado

El Paclitaxel Modula la Proliferación y la Diferenciación de Células THP-1 Expuestas al Virus SARS-CoV-2 Inactivado

https://doi.org/10.32635/2176-9745.RBC.2025v71n2.5107

Everaldo Hertz1; Bárbara Osmarin Turra2; Nathália Cardoso de Afonso Bonotto3; Fernanda dos Santos Trombini4; João Arthur Bittencourt Zimmermann5; Cibele Ferreira Teixeira6; Verônica Farina Azzolin7; Ivo Emilio da Cruz Jung8; Ivana Beatrice Mânica da Cruz9; Fernanda Barbisan10

1-6,9,10Universidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM). Santa Maria (RS), Brasil. E-mails: everaldohertz@gmail.com; barbara.turra@acad.ufsm.br; nathaaliab23@gmail.com; fernandatrombini@gmail.com; joao.zimmermann@acad.ufsm.br; cibelefteixeira@hotmail.com; ivana.ufsm@gmail.com; fernandabarbisan@gmail.com. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-9202-1631; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4175-9534; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3733-3549; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3999-9101; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0009-0006-0771-6687; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0058-3827; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3008-6899; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2960-7047

7,8Fundação Universidade Aberta da Terceira Idade (FUnATI). Manaus (AM), Brasil. E-mails: azzolinveronica@hotmail.com; ivojung@gmail.com. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8191-5450; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0516-7278

Corresponding author: Cibele Ferreira Teixeira. Universidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM). Av. Roraima 1000 – Cidade Universitária – Camobi. Santa Maria (RS), Brasil. CEP 97105-900. E-mail: cibelefteixeira@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Cancer patients were considered a high-risk group for COVID-19. Studies indicate that certain types of cancer, as breast cancer, may exhibit distinct immunological responses. Evidence suggests that paclitaxel (PTX), a chemotherapeutic agent widely used in the treatment of breast cancer, has immunomodulatory properties, which could contribute to attenuate the inflammatory response caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Objective: To evaluate the effect of PTX on the THP-1 immune cells line activated by non-viral immunogenic agent 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) and by inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virus derived from the CoronaVac vaccine (CVac). Method: An in vitro study was conducted, initially determining the minimum concentration of CVac required to activate THP-1 cell. Subsequently, the cytotoxic action of PTX on THP-1 cells was investigated, followed by the analysis of the immunomodulatory effect of PTX through the evaluation of cell proliferation rate, cytomorphological differentiation, levels of nitric oxide, superoxide anion, and gene expression of the cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin 10. Results: In 24-hour, 5% CVac activated THP-1 cells, triggering more significant proliferation and cell differentiation, compared to the control. No cytotoxic effects of PTX were observed. PTX reduced the cell differentiation rate and superoxide levels when co-exposed with TPA or CVac, but did not modulate cytokine gene expression. Conclusion: The data indicate that PTX could modulate in vitro immune activation in response to viral and non-viral immunogenic agents, suggesting that it could attenuate the inflammatory response to antigens, including SARS-CoV-2.

Key words: Breast Cancer/drug therapy; Paclitaxel; COVID-19; Cytokine Release Syndrome; Cytotoxicity, Immunologic/drug effects.

RESUMO

Introdução: Pacientes oncológicos foram considerados grupo de risco para a covid-19. Estudos indicam que determinados tipos de câncer, como o de mama, podem apresentar respostas imunológicas diferenciadas. Evidências sugerem que o paclitaxel (PTX), quimioterápico amplamente utilizado no tratamento do câncer de mama, tem propriedade imunomoduladora, o que poderia contribuir para atenuar a resposta inflamatória causada pelo vírus SARS-CoV-2. Objetivo: Avaliar o efeito do PTX na linhagem de células imunes THP-1 ativadas pelo imunógeno não viral éster de forbol 12-O-tetradecanoilforbol-13-acetato (TPA) e pelo vírus SARS-CoV-2 inativado oriundo da vacina CoronaVac (CVac). Método: Foi conduzido um estudo in vitro constituído, primeiramente, pela determinação da concentração mínima de CVac capaz de ativar as células THP-1. A seguir, foi investigada a ação citotóxica do PTX nas células THP-1, seguida da análise do seu efeito imunomodulador por meio da análise da taxa de proliferação celular, diferenciação citomorfológica, níveis de óxido nítrico, ânion superóxido e expressão gênica das citocinas fator de necrose tumoral alfa e interleucina 10. Resultados: Em 24 horas, a CVac 5% ativou as células THP-1, desencadeando proliferação e diferenciação celular mais significativas que o controle. Nenhum efeito citotóxico de PTX foi observado. O PTX diminuiu a taxa de diferenciação celular e os níveis de superóxido quando exposto concomitantemente com TPA ou CVac, mas não modulou a expressão gênica das citocinas. Conclusão: Os dados indicam que o PTX poderia modular a ativação imunológica in vitro frente a imunógenos virais e não virais, sugerindo que ele poderia atenuar a resposta inflamatória a antígenos, incluindo o SARS-CoV-2.

Palavras-chave: Neoplasias da Mama/tratamento farmacológico; Paclitaxel; COVID-19; Síndrome da Liberação de Citocina; Citotoxicidade Imunológica/efeitos dos fármacos.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Los pacientes oncológicos fueron considerados grupo de riesgo para COVID-19. Los estudios indican que ciertos tipos de cáncer, como el de mama, pueden presentar respuestas inmunológicas diferenciadas. La evidencia sugiere que el paclitaxel (PTX), quimioterápico utilizado para tratar el cáncer de mama, tiene propiedades inmunomoduladoras, lo que podría contribuir a atenuar la respuesta inflamatoria causada por el SARS-CoV-2. Objetivo: Evaluar el efecto de PTX en las células inmunes THP-1 activadas por el inmunógeno no viral éster de forbol 12-O-tetradecanoilforbol-13-acetato (TPA) y por el virus SARS-CoV-2 inactivado proveniente de la vacuna CoronaVac (CVac). Método: Se realizó un estudio in vitro, constituido inicialmente por la determinación de la concentración mínima de CVac capaz de activar las células THP-1. Posteriormente, se investigó la acción citotóxica del PTX en THP-1, seguida del análisis de su efecto inmunomodulador mediante el análisis de la tasa de proliferación celular, diferenciación citomorfológica, niveles de óxido nítrico, anión superóxido y expresión génica de las citocinas factor de necrosis tumoral alfa y interleucina 10. Resultados: En 24 horas, la CVac al 5% activó las células THP-1, desencadenando proliferación y diferenciación celular más significativas que el control. No se observaron efectos citotóxicos del PTX. El PTX disminuyó la tasa de diferenciación celular y los niveles de superóxido, cuando se expuso juntamente con TPA o CVac, pero no moduló la expresión génica de las citocinas. Conclusión: Los datos indican que el PTX podría modular la activación inmunológica in vitro contra inmunógenos virales y no virales, lo que sugiere que podría atenuar la respuesta inflamatoria a antígenos, incluido el SARS-CoV-2.

Palabras clave: Neoplasias de la Mama/tratamiento farmacológico; Paclitaxel; COVID-19; Síndrome de Liberación de Citocinas; Citotoxicidad Inmunológica/efectos de los fármacos.

INTRODUCTION

During the COVID-19 pandemic, epidemiological evidence suggested that breast cancer was associated with a lower risk of complications to develop severe forms of COVID-19, as admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and mechanical ventilation and deaths triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to other types of cancer1-4. A study applying bioinformatics tools, proteomic data, and a SARS-CoV-2 viral replication model suggested that paclitaxel (PTX), a first-line chemotherapy in breast cancer, could present some antiviral activity against the SARS-CoV-2 virus5,6.

The PTX is also administered in association with other drugs, as trastuzumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody to treat metastatic breast cancer7,8. Chemically, PTX is a tricyclic diterpenoid (C47H51NO14) first identified from the bark and needles of Taxus brevifolia. It promotes tubulin assembly into microtubules and prevents their disassembly, blocking cell cycle progression and thus inhibiting tumor growth by halting mitosis. PTX can also block Bcl-2 gene activation and promote apoptosis events. Furthermore, PTX can impact the modulation of immune cells, as macrophages, in breast cancer’s immune-infiltrated environment5,9.

Therefore, PTX could act by attenuating the immune response to non-viral and viral immunogenic molecules. There are two potential, non-exclusive mechanisms through which PTX could act in viral infections as COVID-19: by inhibiting or reducing the viral proliferation rate or by attenuating the inflammatory response. Thus, PTX could prevent a cytokine storm, which is a secondary hyperinflammatory state that can lead to multiple organ failure, coagulopathy, and death10. This prevention could occur through the induction of apoptotic events or the modulation of macrophage polarization.

Here, the PTX effect on THP-1 cell proliferation and differentiation was analyzed. THP-1 cells were used since they are a recognized in vitro experimental model of monocyte/macrophage functions and immune system signalling pathways. This cell line was derived from the peripheral blood of a 1-year-old male with acute monocytic leukemia. THP-1 cells are phagocytic (for latex beads and sensitized erythrocytes) and lack surface and cytoplasmic immunoglobulin11. The relevance of macrophages in the breast tumor microenvironment supports the investigation of PTX immunomodulatory effects using the THP-1 monocytic model12.

To test the effect of PTX on THP-1 cells' immune activation, 24, 48, and 72-h cultures have been exposed to the inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virus present in the CoronaVac (CVac) manufactured by Sinovac Biotech13. A similar protocol was performed by THP-1 exposure to the non-viral agent phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), an immunogenic molecule broadly used to induce macrophage-like cell differentiation in this cell line11,14.

METHOD

The main experimental protocols developed in the study performed using the commercial THP-1 cell line (TIB-202TM, American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), USA) are summarized in Table 1. Cell cultures were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum, 1% antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin), and 1% antifungal amphotericin B. Cell culture was conducted under appropriate temperature conditions (37ºC), CO2 saturation (5%) and sterility. The cell concentration used in the tests was 1x105 cells/mL. All protocols were performed in triplicates. The TPA solution was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instruction Sigma-Aldrich and used at 25 ng/mL concentration.

The THP-1 cell cultures were also exposed to the inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virus (CVac) that is commercially produced by growing in Vero cells and then inactivated with beta-propiolactone. Inactivated virus is mixed with an aluminium hydroxide adjuvant. This traditional approach to vaccine production is like how inactivated polio vaccines are made. The vaccine can be stored at standard refrigerator temperature, making it easier to distribute in regions without advanced cold storage facilities13. To determine the minimum concentration of CVac required to activate the inflammatory response, a study was conducted to investigate the minimum concentration of the immunogen (%) capable of activating the THP-1 cell line through an increase in the proliferation rate, without causing extensive mortality.

The PTX was dissolved in RPMI 1640 medium solution to obtain a concentration of 300 µM in THP-1 cells, which is close to the minimum therapeutic dose of this chemotherapy. Four PTX concentrations below 300 µM with an approximate logarithmic distribution (10, 30, 50 and 100µM) were also evaluated here, considering that direct exposure to PTX could cause undesired cytotoxicity.

Table 1. Summary of the experimental design conducted through protocols

|

Aim |

Treatments

|

Time cultures |

|

Protocol 1 - To compare metabolic activity by MTT assay(*), with the objective of determining the lowest concentration of CVac that can induce cell proliferation. The peak of cellular proliferation will then be compared among the control group, TPA, and CVac |

Control, TPA, CVac

|

24, 48, 72h |

|

Protocol 2 - To determine whether exposure to CVac and the different concentrations of PTX would have a cytotoxic effect on THP-1 cultures by Neutral Red assay |

Control, TPA, CVac, PTX (10,30,50,100, 300 µM) |

24 h |

|

Protocol 3 – To determine the modulation of cell proliferation by exposure to different concentrations of PTX from analysis of metabolic activity determined by MTT assay |

Control, TPA, CVac, PTX (10,30,50,100, 300 µM) |

24 h |

|

Protocol 4 – To compare the induction of cytomorphological changes associated with the differentiation of THP-1 cells into macrophage-like cells by optical microscopy. The presence of cellular clusters and/or presence of non-spherical cells with a spread phenotype were counted as an indicator of cellular differentiation |

Control, TPA, CVac, PTX 300 µM |

24 h |

|

Protocol 5 – To compare the modulation of NO and SA levels, which are biochemical markers of immune response activation in macrophages |

Control, TPA, CVac, PTX 300 µM |

24 h |

|

Protocol 6 – To compare the modulation of the gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α and of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 |

Control, TPA, CVac, PTX 300 µM |

24 h |

(*) MTT assay – (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolic).

The use of cell culture as an experimental model is the main alternative for replacing animals in research experiments. Ethical approval is waived for projects involving cell lines derived from the expansion of primary cell cultures in vitro15 in compliance with Directive 466/1216 of the National Health Council (CNS).

Cell culture medium and reagents for culture were obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, California, USA). Cells were cultured in a humidified incubator (Panasonic, Osaka, Kansai, Japan). All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, Missouri, USA). All analyses involving the measurement of absorbance or fluorescence were performed with a SpectraMax i3x multi-Mode microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, California, USA). Molecular protocols were performed using reagents obtained from Ludwing-Biotec (Alvorada, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil), Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, California, USA), Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, California, USA), and QIAGEN Biotechnology (Hilden, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany). Panoptic dye was commercially obtained through easy-to-apply kits from Laborclin® (Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil). Gene expression by Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) was performed through analysis using determined by a Rotor-Gene Q 5plex HRM System (Qiagen Biotechnology, Hilden, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany). Thermo Scientific NanoDrop™ 1000 Spectrophotometer (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and conventional thermal cycler (Corning Inc., Somerville, Massachusetts, USA) were also used. The microscope used to visualize the histomorphological analysis was an ICX41 inverted biological microscope (Sunny Optical Technology (Group) Co. Ltd., Ningbo, Zhejiang, China).

The effect of all treatments on THP-1 cell proliferation was evaluated by MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolic), a colorimetric assay based on the reduction of a yellow tetrazolium salt (MTT) to purple formazan crystals by metabolically active cells. This reduction occurs through the activity of NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductases in viable cells. MTT assay was performed as described by Mosmann17 and slightly modified by Barbisan et al.18. Briefly, the MTT reagent was dissolved in a 5 mg/mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and added to a 96-well plate with the cells. After incubation for 1 h at 37°C, formed formazan crystals were dissolved with the addition of dimethyl sulfoxide to the reaction, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm. To observe the increase in the cell proliferation rate for each treatment, the mean absorbance ± standard deviation was compared across 24, 48, and 72h cultures. The comparison of cell proliferation intensity among different treatments was made by calculating the percentage relative to the control according to the Guidance Document on Good In Vitro Method Practices19. The following equation was used to calculate % control values: (Treatment Absorbance x 100)/Control Absorbance.

The potential PTX cytotoxic effect on THP-1 cells was determined by a neutral red uptake assay that relies on the ability of living cells to incorporate and bind neutral red, a weak cationic dye, in lysosomes. The neutral red assay was introduced in regulatory recommendations of cytotoxicity analysis20. This assay was performed as described by Repetto et al.21. Briefly, neutral red dye was added to 96-well cell culture plates and incubated for 3h at 37°C in the dark. After incubation, cells were washed with PBS pH 7.4, and 100μL of the desorption solution (50% EtOH, 49% H2O, 1% glacial acetic acid solution) was added, and the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 540 nm. The results were presented as % of control, calculated as previously described.

Just as circulating human monocytes can be differentiated into macrophages and polarized, THP-1 cells can be induced to differentiate through exposure to immunogenic molecules, especially TPA22. When activated, the initially spherical cells reorganize into cellular cords, forming cellular clusters anchored to the bottom of the culture flask. An adapted Panoptic fast staining technique to identify the main differences between non-activated and activated THP-1 cultures was used.

As the cells are non-adherent, 20 µL from the wells containing the respective treatments were collected and transferred onto a histological slide. After drying, fixation and staining were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Non-activated THP-1 cells exhibited a monocyte-like spherical pattern, with non-existent or very short cytoplasmic extensions and scant quantity. Cells were highly stained with a bluish-purple, indicating basic components, with difficult differentiation between nucleus and cytoplasm. Upon exposure to immunogens, the cells display cellular clusters and a more dispersed cellular pattern, with the cytoplasm appearing lighter blue than the nucleus. Additionally, cells with fusiform and stellate patterns resembling macrophages could be observed. Therefore, the number of cellular clusters or cells that were spread out or resembled macrophages from 10 microscopic fields (40x magnification) was counted and compared among the 24h THP-1 culture treatments. Adjustments to the contrast and brightness of the images and the counting of cellular clusters were made using the Image J public domain software23 (version 1.41) for processing and analysing scientific images.

When activated, macrophages produce nitric oxide and superoxide anion, important reactive species in the immune response related to phagocytic processes24. Differentiation induction of THP-1 cells by TPA involves nitric oxide mediation25. Therefore, nitric oxide levels were indirectly estimated by quantifying nitrate levels using the Griess reagent, according to Tatsch et al.26. Superoxide anion levels were spectrophotometrically estimated according to Morabito et al.27. The absorbance of both assays was read at 550 nm.

Gene expression analysis of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) was performed, considering this cytokine as representative of the proinflammatory route. Furthermore, there are some studies, as Son et al.28, describing the inhibitory PTX effect on TNF-α and other proinflammatory cytokines. Additionally, interleukin 10 (IL-10) was analyzed as a representative cytokine of anti-inflammatory response. Total RNA samples were extracted with TriZol following the manufacturer’s instructions by Ludwig Biotechnology and quantified by Thermo Scientific Nanodrop™ 1.000 Spectrophotometer (532 nm wavelength). The reverse transcription was performed using 1 μg/mL RNA from samples. DNA activation in the samples was performed by addition of 0.2 μL of DNase at 37°C for 5 min, followed by heating at 65°C for 10 min. The cDNA was obtained by the action: 1 μL of IScript cDNA and 4 μL of Mix IScript involving the following steps: heating at 25°C for 5 min, at 42°C for 30 min, and at 85°C for 5 min, followed by incubation at 5°C for 60 min. RT-PCR was performed in a 20 μL reaction volume: 1 μL of the cDNA and 19 μL of QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR Kit. The RT-PCR parameters used in the protocol were 95°C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 30 s followed by a melt curve of 65°C. Beta-actin housekeeping gene was used as reference to compare gene expression among treatments and control, calculated using the Ct method. β-actin primer was forward sequence (5’-3’): TGTGGATCAGCAAGCAGGAGTA; reverse sequence (5’-3’): TGCGCAAGTTAGGTTTTGTCA (accession code NM_001101.5). Data were expressed as the fold expression compared to the control. TNF-α primer was forward sequence (5’-3): CAACGGCATGGATCTCAAAGAC; reverse sequence (5’-3’): TATGGGCTCATACCAGGGTTTG (accession code NM_000594.4); IL-10 primer was forward sequence (5-3’): GTGATGCCCCAAGCTGAGA; reverse sequence (5’-3’): TGCTCTTGTTTTCACAGGGAAGA (accession code NM_000572.3).

The quantitative variables were statistically compared among treatments at different concentrations by one-way analysis of variance followed by the Tukey post hoc test and two-way analysis of variance followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. In the statistical comparisons, p < 0.05 was considered significant. Different letters (a, b, c, etc) identified statistical differences among treatments. Statistical analysis and graphs were performed using GraphPad Prism29 (version 9.4).

RESULTS

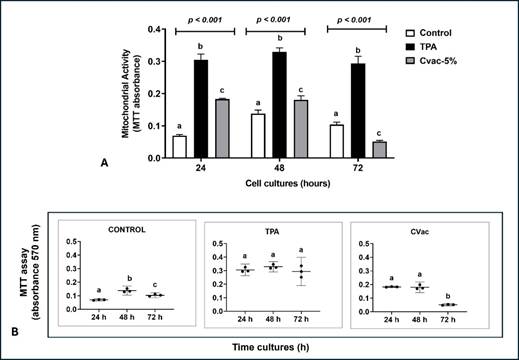

Initially, the CVac concentration capable of activating THP-1 cells was identified using TPA as a positive control (Figure 1A). The lowest concentration of CVac capable of inducing a higher rate of metabolic activity that indicates cellular proliferation in 24h cultures than control was 5%. Data of THP-1 activation at 0.5, 1, 2, and 3% of CVac was not shown since it did not induce significant cellular proliferation compared to the controls. In 48h cultures, CVac remained with higher cellular proliferation than controls. However, in 72h cultures, the CVac-exposed cellular proliferation rate decreased significantly compared to the control. In all time cultures evaluated, the induction in the rate of cellular proliferation by exposure to 5% CVac was lower compared to the cultures exposed to TPA. TPA-exposed cells presented higher metabolic activity than control and CVac in cultures of all times investigated.

Metabolic activity by MTT assay in 24, 48, and 72 h of control and cultures TPA and CVac exposed was performed to identify the peak of cellular proliferation. As shown in Figure 1B, higher metabolic activity was observed in the 48h culture of control than in 24 and 72h in control cells. However, when cells were exposed to TPA, there was no significant difference in metabolic activity of all time cultures analysed. On the other hand, CVac-exposed cultures presented similar metabolic activity in 24 h and 48 h that dropped in 72h cultures. Data indicated that CVac exposure induced THP-1 activation at 5%, mainly in 24h cultures. Therefore, these experimental conditions were used in all subsequent protocols.

Figure 1. Metabolic activity in THP-1 cells measured by the MTT assay, indicative of cell viability and proliferation in 24, 48 and 72 h cultures. (A) Comparison of metabolic activity (% control) among no-treated cells and cells exposed to the non-viral immunogen TPA and viral immunogen, CoronaVac vaccine (CVac), produced from an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virus at 5%. Statistical comparison was performed using One-Way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test. (B) Metabolic activity peak by comparison of absorbance (570 nm) among 24, 48 e 72h cultures of each treatment. Statistical comparison was performed by Two-Way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, comparing treated cells to untreated cells (Control). In all statistical analysis different letters indicate statistical significance at p<0.05

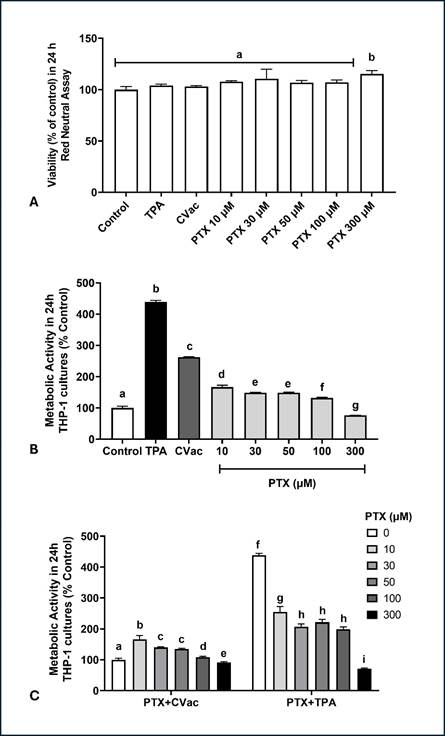

Comparison of cell viability exposed to PTX at different concentrations did not identify the cytotoxic effect of this drug in 24h THP-1 cultures (Figure 2A). The PTX effect on metabolic activity determined by the MTT assay was evaluated hereafter. The higher concentration (300 µM) triggered a significant decrease in metabolic activity, whereas other PTX concentrations showed an increase in metabolic activity than the control (Figure 2B).

A potential interaction between PTX and CVac and PTX and TPA on cellular metabolic activity was also analysed (Figure 2C). In the PTX+CVac interaction, all concentrations increased the metabolic activity of THP-1 cells, except the highest concentration evaluated (300 µM), which reduced this effect. PTX decreased the metabolic activity of cells concomitantly exposed to TPA, with a more intense effect observed at a concentration of 300 µM. Therefore, PTX exerts a lowering impact on the metabolic activity of THP-1 cells with and without interaction with immunogenic TPA and CVac.

Figure 2. Metabolic activity in 24 h cultures of THP-1 cells measured by the MTT assay, exposed to Paclitaxel (PTX) at different concentrations with and without interaction with non-viral immunogen TPA and the viral immunogen, CoronaVac vaccine (CVac). (A) Cellular viability determined by Neutral Red assay; (B) Metabolic activity determined by MTT assay in THP-1 cultures exposed to different concentrations of PTX and to immunogens TPA and CVac; (C) Interaction between PTX with CVac or TPA on metabolic activity of 24 h cultures. Statistical comparisons were performed using a One-Way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test (A, B) or Two-Way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post hoc test (C). The results are presented as percentage relative to the control. Different letters indicate statistical significance at p<0.05

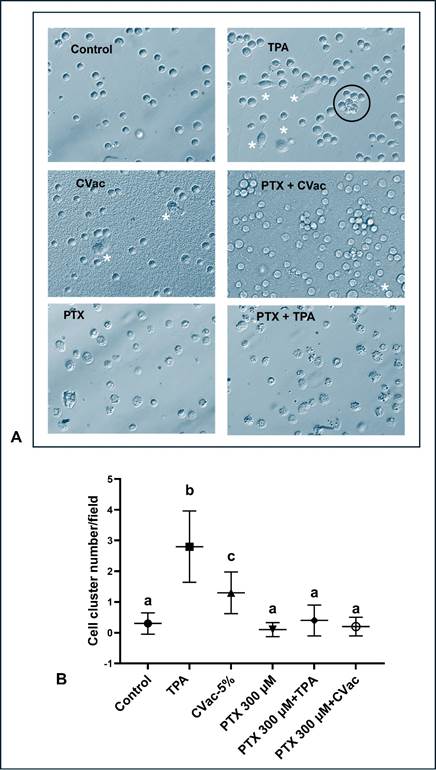

These results evaluated the potential effect of PTX at 300 µM on THP-1 differentiation in 24 h cultures (Figure 3) and showed that the controls maintained an undifferentiated pattern with spherical cells like monocytes. Exposure to TPA and CVac induced the formation of cellular clusters that typically precede or occur concurrently with cytological spreading, making the cells like macrophages. However, in the presence of PTX, the differentiation rate was controlled independently of simultaneous exposure to TPA or CVac.

Figure 3. Cellular differentiation markers (cell cluster indicated by black circle and spreading cells indicated by white asterisks) in 24 h cultures of THP-1 exposed to non-viral immunogenic TPA, viral immunogenic CVac, and Paclitaxel (PTX) at 300 µM concentration. (A) Representative microphotographs obtained from optical microscopy (200 X magnification) were analysed by Image J software; (B) Comparison among treatments of cellular differentiation identified by number of cluster cells and macrophage-like cells. Statistical comparisons were performed using One-Way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, comparing treated cells to untreated cells (control). Different letters indicate statistical significance at p < 0.05

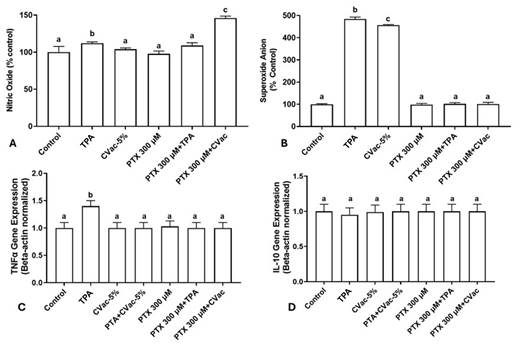

The effect of PTX at 300 µM on the modulation of four oxi-inflammatory markers related to the activation of the immune response in macrophages was evaluated (Figure 4). The cultures exposed to TPA, and PTX 300µM + CVac induced a significant increase in nitric oxide levels, whereas other treatments showed levels like the control in this inflammatory marker. Concurrent exposure to PTX 300µM + CVac was the treatment that caused the greatest increase in nitric oxide concentrations (Figure 4A). Exposure to TPA and CVac induced a significant increase in superoxide anion levels compared to the control. However, exposure to PTX 300 µM, PTX 300µM + TPA, and PTX 300µM + CVac did not differentially modulate superoxide anion levels, as the levels of this marker were like the control (Figure 4B).

Finally, the modulation of gene expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was evaluated in different treatments. Exposure to TPA induced significantly greater overexpression of TNF-α than controls. Conversely, all cultures exposed to CVac and PTX showed similar TNF-α gene expression when compared to the control group (Figure 4C). As can be seen in Figure 4D, exposure to TPA, CVac, and PTX did not differentially modulate the expression of the anti-inflammatory gene IL-10.

Figure 4. Modulation of oxi-inflammatory markers of 24h cultures of THP-1 cells exposed to PTX at 300 µM and non-viral (TPA) and viral (CVac) immunogenic. (A) Nitric oxide; (B) Superoxide anion; (C) TNF-α gene expression; (D) IL-10 gene expression. Gene expression was normalized by the Beta-actin gene. Statistical comparisons were performed using One-Way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test. The results are presented as a percentage relative to the control (untreated cells). Different letters indicate statistical significance at p < 0.05

DISCUSSION

It was observed that the chemotherapeutic agent PTX can modulate the response of THP-1 cells to non-viral (TPA) and viral (CVac) immunogens through changes in proliferation rates, cellular differentiation, and markers associated with the monocytes/macrophages inflammatory activation (nitric oxide, superoxide anion, gene expression of cytokines TNF-α and IL-10). Initially, it is essential to address some considerations about the methodological design of the study that used the CVac vaccine to trigger an immune response in THP-1 cells.

It is important to emphasize the use of THP-1 cells as an experimental model, eliminating the need for complementary studies with other types of immune cell lines. The human THP-1 cell line, derived from leukemic monocytes, is widely used in inflammation studies due to its ability to differentiate into functionally active macrophages30. Therefore, this cell line enables the investigation of antigen-induced inflammatory mechanisms, including those triggered by viruses as SARS-CoV-2, as well as the effects of immunomodulatory agents31.

The relevance of the THP-1 experimental model is based on the following aspects: THP-1 monocytes express Toll-like receptors (TLRs), allowing activation by pathogens and viral components, as SARS-CoV-2 RNA. This activation induces the production of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β, which are essential to understand the cytokine storm observed in COVID-1930.

THP-1 cells are frequently used to evaluate the effects of immunomodulatory compounds, including phytotherapeutics and new synthetic molecules. Experiments using these agents enable the identification of potential modulators of the innate immune response, either by reducing excessive inflammation or by enhancing antiviral defense mechanisms32,33.

When stimulated with TPA, THP-1 cells differentiate into macrophages, which can be polarized into either pro-inflammatory (M1) or anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotypes. This differentiation facilitates the investigation of therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating the inflammatory response33.

THP-1-based models enable the analysis of intracellular signaling pathways activated by antigens and immunomodulators, including the NF-κB, MAPK, and JAK-STAT pathways, which regulate inflammatory and antiviral responses. A study conducted earlier by Pan et al.34 has investigated the activation of inflammation induced by viral proteins, including the SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein, using THP-1 cell cultures.

Therefore, the experimental model utilizing THP-1 cells is included as a relevant methodological strategy for assessing immune-modulatory efficacy in in vitro studies. Using THP-1 cells, researchers can gain insights into how these agents might influence immune responses. This is crucial for understanding their broader implications in diseases as cancer and viral infections35.

The CVac vaccine used to induce THP-1 activation is also known as Sinovac Biotech Ltd. inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and has been widely implemented in combating the COVID-19 pandemic CVac vaccines containing aluminum adjuvants, which induce an effective immune response. Epidemiological studies showed the overall efficacy for preventing symptomatic COVID-19 (before the emergence of variants of concern) using two doses of 3 μg CVac was 67.7% (95% CI, 35.9% to 83.7%)13. To date, 42 clinical trials for CVac have been conducted in eight countries, and CVac has been approved in 56 countries (COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker (trackvaccines.org) accessed in January 2024).

However, most of these investigations primarily aimed to evaluate the immunogenic efficacy of the vaccine. Considering the challenges of experimentally investigating the potential effects of drugs and herbal medicines on modulating the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 exposure, it is postulated the hypothesis of using cell lines as THP-1, exposed to the inactivated virus present in CVac. To achieve this, various experimental protocols were conducted where the concentration of CVac in the culture medium was increased until an immune response was induced in the THP-1 cells. This induction was obtained at a CVac to culture medium ratio of 5%.

The increase in cell proliferation and differentiation rates were considered, as well as an increase in at least one of the oxidative markers (nitric oxide or superoxide anion), as indicators of induction when THP-1 cells were exposed to CVac. To choose the proportion of CVac to be used, the results obtained from at least three markers were evaluated: an increase in cell proliferation rate, induction of differentiation into a phenotype like macrophages, and an increase in superoxide anion levels. However, since the markers of THP-1 activation exposed to CVac were more intense in 24 and 48h cultures, it was decided to conduct the other tests in the initial exposure phase (24h).

Although no prior studies have been found where THP-1 cells were exposed to the inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virus, there are published investigations in the literature where these cells have been exposed to purified proteins from the virus SARS-CoV-2 purified envelop protein (E protein) or purified spike (S) glycoprotein (S protein). Barhoumi et al.30 described that exposure to S protein increased apoptosis, reactive oxygen species generation, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and intracellular calcium expression in the THP-1 macrophages. Additionally, the authors observed that S protein exposure induced the expression of more than 400 proteins in THP-1 cells. Another study performed by Huang et al.36 observed that E protein potently induced cell death in cultured cell lines, including THP-1 cells, in a time-and concentration-dependent manner. These authors limited the analyses to cultures of up to 24h and did not perform tests related to the induction of the immune response by THP-1 cells exposed to the viral protein. Therefore, these studies helped to validate the in vitro model used in which THP-1 cells were exposed to CVac.

An additional remark that deserves further review concerns the differentiation of THP-1 cells upon activation. Although the THP-1 lineage is not primarily composed of macrophages, studies have demonstrated that it reliably differentiates into cells with a macrophage-like phenotype when stimulated by specific agents. The TPA is one of the most used inducers, leading to cell adhesion, increased size, and the expression of typical macrophage markers. For this reason, the differentiation of THP-1 cells into macrophages is widely employed in inflammation studies, provided that appropriate stimulation is applied to facilitate this process. In this context, differentiation induced by exposure to CVac can be considered a marker of THP-1 cell activation33.

Regarding differentiation, the results obtained showed a higher frequency of cell aggregates in the activated cultures. In general, this type of cytomorphological pattern is common in lymphocytes rather than macrophages. However, although it is not typical, previous studies have observed that when stimulated with TPA, THP-1 cells differentiate into adherent macrophages. During this process, they may form clusters due to cell adhesion and cell-to-cell interactions, where there is evidence that TPA-treated THP-1 cells exhibit an increase in the expression of integrins and adhesion molecules, leading to cell aggregation and the formation of cluster-like structures. This is the case of the study conducted by Liu et al.37, which addresses the differentiation of THP-1 monocytes into macrophages using TPA, highlighting the importance of standardized protocols for the effective differentiation of these cells.

As observed in most studies, the triggering of apoptotic events is standard; it can be inferred that the use of the inactivated virus may have attenuated this response, thereby allowing the assessment of the effect of SARS-CoV-2 on cellular activation in the THP-1 cell line. This suggests that the inactivated virus is a valuable tool for evaluating the immunological interactions between THP-1 cells and SARS-CoV-2 without the confounding effects of virus-induced cell death.

Once the in vitro model of THP-1 immune response by CVac was established, it was possible to conduct protocols involving the chemotherapy drug PTX. In this context, it was first investigated whether PTX could induce intense immunosuppression via an increase in the mortality rate of monocytes. The results did not support this hypothesis since THP-1 cultures showed viability like control when exposed to 10 to 100 µM of PTX. They had a slight but significant increase in viability when exposed to the highest concentration evaluated (300 µM). On the other hand, all concentrations of PTX decreased metabolic activation compared to cells exposed to the immunogenic agents TPA and CVac, which could indicate some level of immunosuppression via a decrease in mitotic rate.

This result concurs with the pharmacological activity of PTX since this chemotherapy drug is an anti-microtubule agent38. In THP-1 cells activated by CVac or TPA, treatment of cultures with PTX at 300 µM significantly decreased the rate of metabolic activity. Regarding cellular changes related to inflammatory activation in THP-1 cultures, PTX significantly reduced the formation of cellular aggregates at all concentrations evaluated, which may also be associated with its anti-microtubule action. These results suggest that PTX may have an anti-inflammatory effect under conditions of inflammatory response activation by viral or non-viral pathogens. This property could potentially contribute to modulating the immune response in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment, thus affecting the risk of complications and mortality associated with coronavirus infection.

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), located within the tumor microenvironment (TME), play a significant role in cancer cell survival and progression, promoting tumor growth, angiogenesis, and immune evasion12. TAMs are genetically stable cells; however, a cancer cell can acquire new adaptations to survive in an unfavorable TME. Notably, TAMs in breast tumors tend to exhibit an immunosuppressive M2-like phenotype, which is associated with poor prognosis. Nevertheless, some chemotherapeutic agents, as PTX, have been reported to induce TAM repolarization towards a pro-inflammatory M1-like phenotype, potentially contributing to antitumor immunity33. This unique immunomodulatory effect may partially explain why breast cancer patients treated with PTX exhibit different immune responses compared to patients with other cancer types. Given that THP-1 cells are a recognized model for macrophage differentiation and polarization, the present study provides relevant in vitro evidence that PTX may modulate macrophage activation under exposure to viral and non-viral immunogens, potentially reflecting part of the in vivo immunological dynamics in breast cancer.

Although PTX is used in the treatment of various types of cancer, the immunomodulatory effects observed in this investigation may be particularly associated with the characteristics of the breast cancer tumor microenvironment. Unlike other solid tumors, breast cancer exhibits a higher infiltration of monocytes and macrophages, which, as previously mentioned, play decisive roles in either promoting or containing tumor progression, depending on their phenotypic activation39. Therefore, even if PTX does not exert the same effects in other types of cancer, its action on innate immune system cells, as macrophages, may have a differential impact on neoplasms with a strong immunological component and a high density of TAMs, as is the case with breast cancer. Indeed, studies have demonstrated that PTX can induce TAM repolarization towards a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype through a TLR4-dependent pathway, contributing to a more effective antitumor response40.

It is essential to comment on the main methodological limitations of this in vitro study associated with the fact that, in an in vivo infection event, different types of cells and physiological responses are mobilized, which contribute to the establishment of uncontrolled situations, as storm of cytokines, as well as the action of drugs, including PTX.

One of the intriguing questions related to coronavirus infection has been the differences in the risk of complications and death among patients with several types of cancer. Studies have reported specifically that breast cancer patients may have a lower risk, as observed in a survey conducted by the research team4. Another limitation concerns the fact that PTX is also a chemotherapy drug used in other types of cancer, which did not present a lower risk of complications from COVID-19. This fact does not make the study irrelevant, considering that there are complex relationships that could be evaluated to understand why breast cancer would not produce such a substantial risk of morbidity and mortality via infection by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In this scenario, treatment with PTX could mitigate this risk via immunomodulatory action. Therefore, the results also support the suggestion obtained from an in silico study by Adhami et al.6 on the potential effect of PTX on SARS-CoV-2 infection. The role of PTX and similar chemotherapeutic agents in the context of viral infections warrants further investigation to understand their potential benefits and mechanisms of action.

CONCLUSION

Despite the methodological limitations associated with in vitro studies, the results described indicate that PTX could have an attenuating effect on the inflammatory response triggered by SARS-CoV-2, without necessarily having an immunosuppressive effect through the induction of apoptotic events and/or a significant reduction in cell proliferation rate. Thus, the potential influence of this chemotherapeutic agent in reducing complications in breast cancer patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, including cytokine storm, cannot be dismissed. This would not be the sole causal component of the lower risk among breast cancer patients and morbidity-mortality, as cancer patients present highly complex conditions.

CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors contributed substantially to the study design, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing and critical review. They approved the final version for publication.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

There is no conflict of interests to declare.

FUNDING SOURCES

National Council for Scientific and Technological Development – CNPq, FAPERGS (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul), and CAPES (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel).

REFERENCES

1. Chai C, Feng X, Lu M, et al. One-year mortality and consequences of COVID‐19 in cancer patients: a cohort study. IUBMB Life. 2021;73(10):1244-56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/iub.2536

2. Alagoz O, Lowry KP, Kurian AW, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on breast cancer mortality in the US: estimates from collaborative simulation modeling. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(11):1484-94. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djab097

3. Pinato DJ, Tabernero J, Bower M, et al. Prevalence and impact of COVID-19 sequelae on treatment and survival of patients with cancer who recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection: evidence from the OnCovid retrospective, multicentre registry study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(12):1669-80. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00573-8

4. Hertz E, Cruz IBM, Gonçalves CFA, et al. Does breast cancer have a lower risk of mortality from severe acute respiratory syndrome compared to other types of cancer? Evidence from Brazil, a heterogeneous population. Contrib LAS Cienc Soc. 2023;16(12):32178-97. doi: https://doi.org/10.55905/revconv.16n.12-186

5. Abu Samaan TM, Samec M, Liskova A, et al. Paclitaxel’s mechanistic and clinical effects on breast cancer. Biomolecules. 2019;9(12):789. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9120789

6. Adhami M, Sadeghi B, Rezapour A, et al. Repurposing novel therapeutic candidate drugs for coronavirus disease-19 based on protein-protein interaction network analysis. BMC Biotechnol. 2021;21(1):22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12896-021-00680-z

7. Dan VM, Raveendran RS, Baby S. Resistance to intervention: paclitaxel in breast cancer. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2021;21(10):1237-68. doi: https://doi.org/10.2174/1389557520999201214234421

8. Debien V, Marta GN, Agostinetto E, et al. Real-world clinical outcomes of patients with stage I HER2-positive breast cancer treated with adjuvant paclitaxel and trastuzumab. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2023;190:104089. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2023.104089

9. Zhu L, Chen L. Progress in research on paclitaxel and tumor immunotherapy. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2019;24(1):40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11658-019-0164-y

10. Zanza C, Romenskaya T, Manetti AC, et al. Cytokine storm in COVID-19: Immunopathogenesis and therapy. Medicina (Mex). 2022;58(2):144. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58020144

11. Mohd Yasin ZN, Mohd Idrus FN, Hoe CH, et al. Macrophage polarization in THP-1 cell line and primary monocytes: a systematic review. Differentiation. 2022;128:67-82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diff.2022.10.001

12. Dallavalasa S, Beeraka NM, Basavaraju CG, et al. The role of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) in cancer progression, chemoresistance, angiogenesis and metastasis - Current status. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28(39):8203-36. doi: https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867328666210720143721

13. Jin L, Li Z, Zhang X, et al. CoronaVac: a review of efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the inactivated vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(6):2096970. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2096970

14. Lund ME, To J, O’Brien BA, et al. The choice of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate differentiation protocol influences the response of THP-1 macrophages to a pro-inflammatory stimulus. J Immunol Methods. 2016;430:64-70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2016.01.012

15. Geraghty RJ, Capes-Davis A, Davis JM, et al. Guidelines for the use of cell lines in biomedical research. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(6):1021-46. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.166

16. Conselho Nacional de Saúde (BR). Resolução n° 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. Aprova as diretrizes e normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF. 2013 jun 13; Seção I:59.

17. Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65(1-2):55-63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4

18. Barbisan F, Motta JDR, Trott A, et al. Methotrexate-related response on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells may be modulated by the Ala16Val-SOD2 gene polymorphism. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e107299. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0107299

19. Organização para Cooperação e Desenvolvimento Econômico. Guidance document on good in vitro method practices. Paris: OECD; 2018. (OECD Series on testing and assessment)

20. Ates G, Vanhaecke T, Rogiers V, et al. Assaying cellular viability using the neutral red uptake assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1601:19-26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6960-9_2

21. Repetto G, Del Peso A, Zurita JL. Neutral red uptake assay for the estimation of cell viability/cytotoxicity. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(7):1125-31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2008.75

22. Baxter EW, Graham AE, Re NA, et al. Standardized protocols for differentiation of THP-1 cells to macrophages with distinct M(IFNγ+LPS), M(IL-4) and M(IL-10) phenotypes. J Immunol Methods. 2020;478:112721. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2019.112721

23. Rasband WS. ImageJ software [Internet]. version 1.41. Bethesda: U.S. National Institutes of Health; 2009. [Acesso 2025 jan 25]. Disponivel em: https://imagej.net/ij/index.html

24. Weigert A, Von Knethen A, Fuhrmann D, et al. Redox-signals and macrophage biology. Mol Aspects Med. 2018;63:70-87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2018.01.003

25. Chang YY, Lu CW, Jean WH, et al. Phorbol myristate acetate induces differentiation of THP-1 cells in a nitric oxide-dependent manner. Nitric Oxide. 2021;109-110:33-41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.niox.2021.02.002

26. Tatsch E, Bochi GV, Pereira RDS, et al. A simple and inexpensive automated technique for measurement of serum nitrite/nitrate. Clin Biochem. 2011;44(4):348-50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.12.011

27. Morabito C, Rovetta F, Bizzarri M, et al. Modulation of redox status and calcium handling by extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields in C2C12 muscle cells: a real-time, single-cell approach. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48(4):579-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.005

28. Son SS, Kang JS, Lee EY. Paclitaxel ameliorates palmitate-induced injury in mouse podocytes. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2020;26. doi: https://doi.org/10.12659/MSMBR.928265

29. Graph Pad: Prism [Internet]. Versão 9.4. Boston: GraphPad; 2020. [acesso 2024 dez 19]. Disponível em: https://www.graphpad.com/updates/prism-900-release-notes

30. Chanput W, Mes JJ, Wichers HJ. THP-1 cell line: an in vitro cell model for immune modulation approach. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;23(1):37-45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2014.08.002

31. Barhoumi T, Alghanem B, Shaibah H, et al. SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus spike protein-induced apoptosis, inflammatory, and oxidative stress responses in THP-1-like-macrophages: potential role of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (perindopril). Front Immunol. 2021;12:728896. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.728896

32. Albrahim T, Alnasser MM, Al-Anazi MR, et al. In vitro studies on the immunomodulatory effects of pulicaria crispa extract on human THP-1 monocytes. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:7574606. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/7574606

33. Yasin ZNM, Idrus FNM, Hoe CH, et al. Macrophage polarization in THP-1 cell line and primary monocytes: a systematic review. Differentiation. 2022;128:67-82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diff.2022.10.001

34. Pan P, Shen M, Yu Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 N protein promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation to induce hyperinflammation. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):4664. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25015-6

35. Khatua S, Simal-Gandara J, Acharya K. Understanding immune-modulatory efficacy in vitro. Chem Biol Interact. 2022;352:109776. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2021.109776

36. Huang H, Li X, Zha D, et al. SARS-CoV-2 e protein-induced THP-1 pyroptosis is reversed by Ruscogenin. Biochem Cell Biol. 2023;101(4):303-12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1139/bcb-2022-0359

37. Liu T, Huang T, Li J, et al. Optimization of differentiation and transcriptomic profile of THP-1 cells into macrophage by PMA. PLoS One. 2023;18(7):e0286056. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0286056

38. Asnaashari S, Amjad E, Sokouti B. Synergistic effects of flavonoids and paclitaxel in cancer treatment: a systematic review. Cancer Cell Int. 2023;23(1):211. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-023-03052-z

39. Shapouri-Moghaddam A, Mohammadian S, Vazini H, et al. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(9):6425-40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.26429

40. Wanderley CW, Colón DF, Luiz JPM, et al. Paclitaxel reduces tumor growth by reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages to an M1 profile in a TLR4-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2018;78(20):5891-900. doi: https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3480

Recebido em 10/2/2025

Aprovado em 7/4/2025

Associate-editor: Tatiana de Almeida Simão. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8509-2247

Scientific-editor: Anke Bergmann. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1972-8777

![]()

Este é um artigo publicado em acesso aberto (Open Access) sob a licença Creative Commons Attribution, que permite uso, distribuição e reprodução em qualquer meio, sem restrições, desde que o trabalho original seja corretamente citado.