Five-Year Survival and Associated Factors in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer in the Brazilian Amazon

Sobrevida em Cinco Anos e Fatores Associados em Pacientes com Câncer de Cabeça e Pescoço na Amazônia Brasileira

Supervivencia a Cinco Años y Factores Asociados en Pacientes con Cáncer de Cabeza y Cuello en la Amazonia Brasileña

https://doi.org/10.32635/2176-9745.RBC.2025v71n4.5260

Lorena Cristine Soares Epaminondas1; Maikon da Silva e Silva2; Myara Cristiny Monteiro Cardoso3; Leonardo Breno do Nascimento de Aviz4; Maria Conceição Nascimento Pinheiro5; Vânia Cristina Campelo Barroso Carneiro6; Laura Maria Tomazi Neves7; Saul Rassy Carneiro8

1,6Universidade do Estado do Pará (UEPA). Belém (PA), Brasil. E-mails: lorena.soaress@hotmail.com; vania_barroso@yahoo.com.br. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9490-8401; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7277-4652

2,3,8Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA), Hospital Universitário João de Barros Barreto (HUJBB), Laboratório de Avaliação e Reabilitação das Disfunções Cardiovascular, Oncológica e Respiratória (LACOR), Programa de Residência de Fisioterapia em Oncologia. Belém (PA), Brasil. E-mail: maikon12.ms@gmail.com; myaracardoso@gmail.com; saul@ufpa.br. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2566-0569; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2456-8034; Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6825-0239

4UFPA, Núcleo de Medicina Tropical. Belém (PA), Brasil. E-mail: leonardoaviz@ufpa.br. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1760-660X

5UFPA, Núcleo de Medicina Tropical, Laboratório de Pesquisa em Toxicologia Humana e de Estresse Oxidativo. Belém (PA), Brasil. E-mail: mconci7@gmail.com Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2904-9583

7UFPA, LACOR. Belém (PA), Brasil. E-mail: lmtomazi@ufpa.br. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3115-2571

Corresponding autor: Myara Cristiny Monteiro Cardoso. Travessa Barão do Triunfo, 1108 – Pedreira. Belém (PA), Brasil. CEP 66080-680. E-mail: myaracardoso@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Head and neck cancer accounts for approximately 660,000 new cases annually worldwide and is increasing due to the consequences of interactions among environmental, socioeconomic and genetic factors, making it a multifactorial dysfunction. Objective: To verify the five-year survival and associated factors in patients diagnosed with head and neck cancer in a reference cancer hospital in the Amazon. Method: Hospital-based retrospective cohort study with analysis of 510 medical records of patients admitted and followed up at the hospital from 2009 to 2014, the data were collected between August and November of 2020. The Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test were utilized for the statistical analysis, in addition to the Cox regression model to verify the influence of variables on survival time, considering a significance of 0.05. Results: The overall survival rate was 74.7%, socio-demographic variables as women and living in state’s inner cities were associated with the highest survival rates (84.4% and 79.4%, respectively). The clinical variables advanced staging, indication for physiotherapy and smoking were associated with the lowest survival rates with 49.1%, 16.6% and 66.5%, respectively. Conclusion: Sociodemographic and clinical factors are involved in the survival of patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer; in addition, early diagnosis and smoking cessation could potentially increase the survival of these patients.

Key words: Head and Neck Neoplasms; Survival; Demography.

RESUMO

Introdução: O câncer de cabeça e pescoço é responsável por cerca de 660 mil casos novos anualmente no mundo e cresce com as consequências das interações entre os fatores ambientais, socioeconômicos e a herança genética sendo uma disfunção multifatorial. Objetivo: Verificar a sobrevida em cinco anos e os fatores associados em pacientes com diagnóstico de câncer de cabeça e pescoço no hospital de referência de câncer na Amazônia. Método: Estudo de coorte retrospectivo de base hospitalar, com análise de 510 prontuários de pacientes diagnosticados e acompanhados pelo referido hospital no período de 2009 a 2014, coletados entre os meses de agosto e novembro de 2020. A análise estatística utilizou o método de Kaplan-Meier e o teste log-rank, além do modelo de regressão de Cox, para verificar a influência das variáveis no tempo de sobrevida, considerando uma significância de 0,05. Resultados: A taxa de sobrevida geral foi de 74,7%, as variáveis sociodemográficas como sexo feminino e procedência de municípios do interior estiveram associadas com maiores taxas de sobrevida (84,4% e 79,4% respectivamente). Em relação às variáveis clínicas, o estadiamento mais avançado, a indicação de tratamento fisioterapêutico e o tabagismo estiveram associados às menores taxas de sobrevida com 49,1%, 16,6% e 66,5%, respectivamente. Conclusão: Fatores sociodemográficos e fatores clínicos estão envolvidos com a sobrevida de pacientes em tratamento de cânceres de cabeça e pescoço, além disso deve-se buscar o diagnóstico mais precoce e combater o tabagismo, a fim de aumentar as taxas de sobrevida desses pacientes.

Palavras-chave: Neoplasias de Cabeça e Pescoço; Sobrevida; Demografia.

RESUMEN

Introducción: El cáncer de cabeza y cuello representa aproximadamente 660 000 nuevos casos anuales en el mundo y crece con las consecuencias de las interacciones de factores ambientales, socioeconómicos y genéticos, constituyendo una disfunción multifactorial. Objetivo: Verificar la supervivencia a cinco años y los factores asociados en pacientes diagnosticados con cáncer de cabeza y cuello en el hospital de referencia oncológica en la Amazonia. Método: Estudio de cohorte retrospectivo de base hospitalaria, en el que se analizaron 510 historias clínicas de pacientes diagnosticados y con seguimiento en el citado hospital entre 2009 y 2014, recolectadas entre agosto y noviembre de 2020. El análisis estadístico utilizó el método de Kaplan-Meier y la prueba de log-rank, además del modelo de regresión de Cox, para verificar la influencia de las variables en el tiempo de supervivencia, considerando un nivel de significación de 0,05. Resultados: La tasa de supervivencia global fue del 74,7 %, y las variables sociodemográficas, como el sexo femenino y la procedencia de municipios del interior, se asociaron a mayores tasas de supervivencia (84,4 % y 79,4 %, respectivamente). En cuanto a las variables clínicas, la estadificación más avanzada, la indicación de tratamiento fisioterapéutico y el tabaquismo se asociaron a menores tasas de supervivencia con el 49,1 %, 16,6 % y 66,5 %, respectivamente. Conclusión: Los factores sociodemográficos y clínicos intervienen en la supervivencia de los pacientes sometidos a tratamiento por cáncer de cabeza y cuello. Además, es necesario buscar un diagnóstico temprano y combatir el tabaquismo para aumentar las tasas de supervivencia de estos pacientes.

Palabras clave: Neoplasias de Cabeza y Cuello; Sobrevida; Demografía.

INTRODUCTION

Oncological diseases are a major public health problem worldwide. In many countries, they are the leading or second-leading cause of premature mortality before 70 years of age. In Brazil, estimates for the triennium 2023-2025 indicate that 704,000 new cancer cases will occur, one of the leading causes of death1.

Head and neck cancer (HNC) is a heterogeneous group of tumors classified according to their anatomical location. Around 90% of HNCs are squamous cell carcinomas, arising from the epithelial lining of the oral cavity, pharynx and larynx2.

HNCs are responsible for approximately 660,000 new cases and 325,000 deaths worldwide each year, making them the seventh most common type of cancer. They are more prevalent in men than in women2. In Brazil, the estimated number of new oral cavity cancer cases for each year of the triennium 2023-2025 is 15,100, the eighth most common type of cancer. In the state of Pará, the estimate for the same period is 400 cases of oral cavity and larynx cancer combined. For this estimate, cancers of the oral cavity were tumors classified according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)3 codes C00 to C10 (lip, oral cavity, salivary glands and oropharynx)1.

HNC cases are rising due to the interaction of environmental, socioeconomic, and genetic factors, making it a multifactorial disorder. However, lifestyle-related factors, particularly tobacco use combined with alcohol consumption, are the primary contributors, with a synergistic effect when both substances are used concurrently2.

Early-stage HNC diagnosis has a high curative potential; however, delays in diagnosis and treatment initiation often lead to advanced stages requiring more aggressive therapies, which are generally associated with poorer prognoses. Such delays may occur due to silent tumors that are difficult to detect or the slow onset of overt symptoms, which makes it challenging for patients to recognize and seek timely medical care4.

Selecting treatment options requires the analysis of a series of factors, as the location of the primary tumor, the extent of the disease, the patient's age and comorbidities, their preferences, and the morbidity of each treatment approach. The modalities of treatment are surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, either alone or combined5.

Delays to start treatment primarily affect patients with tumors that exhibit accelerated cell proliferation. Therefore, if tumors are detected at an advanced stage, they become aggressive, resulting in low survival rates. Strategies to improve survival rates for these patients should focus on improving the speed of care, as this is a key factor to ameliorate the quality of oncological care4,6.

The high estimates of new cancer cases and deaths in Brazil, combined with the complexity of HNC and its association with risk factors and delayed diagnosis, highlight the urgent necessity of investigation to optimize the management of the disease. The region's geographical and socio-economic particularities, combined with the challenges of accessing healthcare, raise important questions about the impact of these factors on patients' prognoses and how this may differ significantly from other country regions. Therefore, it is crucial to understand HNC survival in this context and identify the influencing factors.

This study aims to address this knowledge gap by providing specific epidemiological data on HNC patient survival, which is essential for improving public health strategies and supporting prevention, early diagnosis and treatment policies to enhance the prognosis of the disease in Brazil, particularly in the Amazon region. In addition, the five-year survival rate of patients diagnosed with HNC and associated factors were analyzed based on data collected at the “Hospital Ophir Loyola”, a reference oncology center in Belém, Pará in the Amazon Region.

METHOD

Hospital-based retrospective cohort study to analyze survival and its associated factors in patients with head and neck cancer at a reference hospital for oncological treatment in the Amazon region.

Data were obtained by evaluating the medical records of patients hospitalized between 2009 and 2014. The following study variables were considered: sex; age (18–30 years, 31-60 years, over 60 years); marital status (single, married, widow/widower); origin (Metropolitan Region of Belém, state’s inner cities); education (illiterate, elementary school, high school, higher education); occupation (employed, unemployed, retired); tumor staging (in situ, local, advanced); and treatment received (exclusive, combined, or none), physiotherapy treatment, comorbidities (none, one, or two or more), referral to palliative care, smoking status (smoker, ex-smoker, or never smoked), alcohol consumption (yes, no), presence of metastasis, pathological fractures, infections, readmissions, and survival time.

The patients classified according to the ICD-10 codes were included in the study (Table 1).

|

Table 1. Location of head and neck cancer types based on ICD-10 |

|

|

Anatomical location |

ICD-10 code |

|

Malignant neoplasms of lip |

C00 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of base of tongue |

C01 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of other and unspecified part of tongue |

C02 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of gum |

C03 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of floor of mouth |

C04 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of palate |

C05 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of other and unspecified parts of mouth |

C06 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of parotid gland |

C07 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of other and unspecified major salivary glands |

C08 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of tonsil |

C09 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of oropharynx |

C10 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of nasopharynx |

C11 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of piriform sinus |

C12 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of hypopharynx |

C13 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of other and ill-defined sites in the lip, oral cavity and pharynx |

C14 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of nasal cavity and middle ear |

C30 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of accessory sinuses |

C31 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of larynx |

C32 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of skin of other and unspecified parts of face |

C44.3 |

|

Malignant neoplasm of the thyroid gland |

C73 |

Caption: ICD-10: International Classification of Diseases 10th edition3.

Patients with incomplete medical records or missing study variables or who did not return to the hospital after cancer diagnosis or for further treatment were excluded.

Medical records were retrieved through an active search in the files of the Division of Medical and Statistical Records (DAME) and the Hospital Cancer Registry (RHC) of the “Hospital Ophir Loyola”. Data were collected from August to November 2020 using a Microsoft 2013 Excel spreadsheet form prepared by the authors. The records were anonymized and identified by a numerical code.

Hospital records were randomized using probabilistic sampling with replacement, following a simple random sample test, with a sampling error of 5% and a significance level of 95%. Survival was calculated as the interval between the date of diagnosis, whether biopsy or surgery, and the date of death or the last recorded follow-up. Follow-up was limited to a maximum of five years; patients alive after this period were excluded from the analysis.

Case selection was randomized and, if a selected record was excluded, the subsequent case was analyzed instead. Data analysis was performed using SPSS7 22.0 software (International Business Machines, NY, USA). The survival curve was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method8 to describe the probability of survival over time. The log-rank test was applied to each independent variable in relation to survival time to compare the curves between groups8. Variables with a significance level of less than 20% were included in the multivariate Cox regression analysis, which estimated proportional hazards over the observation period. Variables with a p-value < 0.05 in the Cox model were considered to have a significant influence on patient survival8.

The survival study, as a statistical method, evaluates a phenomenon over a specific timeframe between an initial and a final event. In the context of healthcare, it helps professionals to understand disease behavior and derive actionable results to improve the quality of life of affected individuals8.

The Ethics Committee of “Hospital Ophir Loyola” approved the study, report 4,115,156 (CAAE submission for ethical review 32561420.6.0000.5550) in compliance with Directive 466/12 of the National Health Council (CNS)9.

RESULTS

A total of 2,182 HNC cases were found between 2009 and 2014. Of these, 510 were included in this study. During this cohort's five-year follow-up period, 129 deaths occurred, reaching an overall survival rate of 74.7%. Patient survival was analyzed according to each clinical and sociodemographic variable to determine whether any significant impact affected individual survival.

Table 2 presents the sample characteristics, predominantly formed by males (52.2%), aged 31–60 years (48.4%), married (60.0%), living in state’s inner cities (63.7%) and with a low level of education (79.8%, up to eight years). Most cases were at an advanced stage of the disease (43.9%), with combined treatment being the most frequent therapeutic modality (50.2%). Only 14.1% of the individuals received physical therapy, 19.6% received palliative care, and 22.8% were readmitted. 66.1% of the patients smoked and 55.7% consumed alcohol. Metastases occurred in only 4.3% of the cases, while pathological fractures (0.2%) and infections (1.8%) were rare events.

|

Table 2. Characteristics of the sample |

|

||||||

|

Characteristics |

N and (%) |

Characteristics |

N and (%) |

|

|||

|

Age group |

|

Physiotherapeutic treatment |

|

|

|||

|

18-30 |

24 (4.7) |

Yes |

72 (14.1) |

|

|||

|

31-60 |

247 (48,4) |

No |

438 (85.9) |

|

|||

|

61-00 |

239 (46.9) |

Palliative Care |

|

|

|||

|

Sex |

|

Yes |

100 (19.6) |

|

|||

|

Female |

244 (47.8) |

No |

410 (80.4) |

|

|||

|

Male |

266 (52.2) |

Comorbidities |

|

|

|||

|

Marital status |

|

Only one |

172 (33.7) |

|

|||

|

Single |

122 (23.9) |

Two or more |

42 (8.2) |

|

|||

|

Married |

306 (60.0) |

None |

296 (58.1) |

|

|||

|

Widow/Widower |

82 (16.1) |

Readmission |

|

|

|||

|

Residence |

|

Yes |

116 (22.8) |

||||

|

MRB* |

185 (36.3) |

No |

394 (77.2) |

|

|||

|

State’s inner cities |

325 (63.7) |

Smoking |

|

|

|||

|

Education |

|

Smoker/Ex-smoker |

337 (66.1) |

|

|||

|

Up to eight years |

407 (79.8) |

Never smoked |

173 (33.9) |

|

|||

|

More than eight |

103 (20.2) |

Alcohol consumption |

|

|

|||

|

Occupation |

|

Yes |

284 (55.7) |

|

|||

|

Employee |

372 (72.9) |

No |

226 (44.3) |

|

|||

|

Unemployed |

92 (18.1) |

Metastasis |

|

|

|||

|

Retired |

46 (9.0) |

Yes |

22 (4.3) |

|

|||

|

Staging |

|

No |

488 (95.7) |

|

|||

|

In situ |

135 (26.5) |

Pathological fractures |

|

|

|||

|

Local |

151 (29.6) |

Yes |

1 (0.2) |

|

|||

|

Advanced |

224 (43.9) |

No |

509 (99.8) |

|

|||

|

Treatment |

|

Infections |

|

|

|||

|

Exclusive |

236 (46.3) |

Yes |

9 (1.8) |

|

|||

|

Combined |

256 (50.2) |

No |

501 (98.2) |

|

|||

|

None |

18 (3.5) |

|

|

|

|||

Caption: *MRB: Metropolitan Region of Belém.

Table 3 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the patients, including the results of the survival analysis: number of deaths, median survival and the log-rank test, which compares the estimated hazard functions for each observed event. The Cox regression analysis determined the independent variables that intensified the time between disease diagnosis and death.

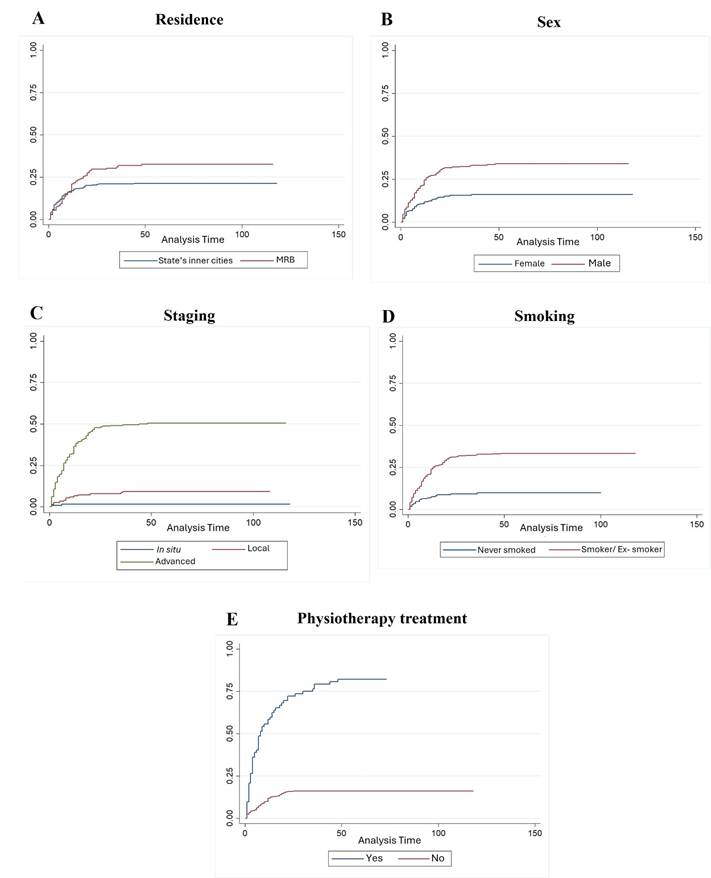

The bivariate analysis of survival in patients with HNC revealed that age group, sex, city of residence and level of education were statistically and significantly associated with survival rate (log-rank test). Patients aged 18-30 had the highest survival rate (91.7%), while those aged 61 or over had the lowest (69.0%) (p = 0.007). Females had significantly higher survival rates (84.4%) than males (65.8%) (p < 0.001), a finding confirmed by the Cox regression analysis (p < 0.001). Individuals living in the state’s inner cities had a higher survival rate (79.4%) than those in the Metropolitan Region of Belém (66.5%) (p = 0.004), a difference that was also evident in the multivariate analysis (p = 0.004). Patients with more than eight years of education had higher survival rates (83.5%) than those with less years of education (72.5%) (p = 0.024), though this variable was not significant in the Cox regression analysis (p = 0.200). These results suggest that sociodemographic factors, particularly sex and place of residence, significantly impact the survival of these patients.

|

Table 3. Bivariate analysis of survival in patients with head and neck cancer and Cox regression for multivariate analysis (sociodemographic variables). Belém, Pará, Brazil, 2009-2014 |

||||

|

Deaths (N) and (%) |

Rate (%) |

Log-rank test |

Cox regression |

|

|

Age group |

|

|

0.007 |

0.159 |

|

18-30 |

2 (1.5) |

91.7 |

|

|

|

31-60 |

53 (41.1) |

78.5 |

|

|

|

61-100 |

74 (57.4) |

69.0 |

|

|

|

Sex |

|

|

0.000 |

0.000 |

|

Female |

38 (29.5) |

84.4 |

|

|

|

Male |

91 (70.5) |

65.8 |

|

|

|

Residence |

|

|

0.004 |

0.004 |

|

MRB |

62 (48.1) |

66.5 |

|

|

|

State’s inner cities |

67 (51.9) |

79.4 |

|

|

|

Education |

|

|

0.024 |

0.200 |

|

Up to eight years |

112 (86.8) |

72.5 |

|

|

|

More than eight |

17 (13.2) |

83.5 |

|

|

|

Total |

129 (25.3) |

74.7 |

- |

- |

Captions: *SV Rate = Survival Rate. MRB = Metropolitan Region of Belém. (-) Not applicable.

Table 4 presents the analysis of clinical characteristics, revealing that disease staging had a strong influence on survival. There were significantly higher survival rates in the early stages (99.3% in situ) and significantly lower rates in advanced cases (49.1%) (p < 0.001). Smoking was also associated with poorer survival outcomes (66.5% among smokers/former smokers versus 90.8% among non-smokers), which was significant in the multivariate analysis (p = 0.006). Patients undergoing physical therapy had a lower survival rate (16.7%), suggesting an association with higher clinical severity (p < 0.001). Bivariate analysis showed significance for treatment, palliative care, presence of comorbidities, alcohol consumption and metastases, but these did not remain as independent factors in the Cox regression. Hospital readmission and infections were not statistically associated with survival. HNC treatments performed at the hospital include surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, radioiodine therapy and others. Treatment choice varied greatly and depended primarily on the stage of the disease.

The log-rank test revealed that the following variables were selected for the Cox regression model: tumor staging, clinical treatment, physical therapy, palliative care, comorbidities (including smoking status), alcohol consumption, metastasis and pathological fractures. After analyzing each independent variable in relation to survival time, the results showed that tumor staging, physical therapy and smoking status significantly influenced survival.

|

Table 4. Bivariate analysis of survival in patients with head and neck cancer plus Cox regression for multivariate analysis (clinical variables). Belém, Pará, Brazil, 2009-2014 |

||||

|

Deaths (N) and % |

Rate (%) |

Log-rank test |

Cox regression |

|

|

Staging |

|

|

0.000 |

0.000 |

|

In situ |

1 (0.8) |

99.3 |

|

|

|

Local |

14 (10.8) |

90.7 |

|

|

|

Advanced |

114 (88.4) |

49.1 |

|

|

|

Treatment |

|

|

0.000 |

0.856 |

|

Exclusive |

50 (38.8) |

78.8 |

|

|

|

Combined |

64 (49.6) |

75.0 |

|

|

|

None |

15 (11.6) |

16.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.000 |

0.000 |

|

|

Yes |

60 (46.5) |

16.7 |

|

|

|

No |

69 (53.5) |

84.2 |

|

|

|

Palliative Care |

|

|

0.000 |

0.671 |

|

Yes |

62 (48.1) |

38.0 |

|

|

|

No |

67 (51.9) |

83.7 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.005 |

0.251 |

|

|

Only one |

32 (24.8) |

81.4 |

|

|

|

Two or more |

17 (13.2) |

59.5 |

|

|

|

None |

80 (62.0) |

73.0 |

|

|

|

Readmission |

|

|

0.320 |

-** |

|

Yes |

31 (24.0) |

73.3 |

|

|

|

No |

98 (76.0) |

75.1 |

|

|

|

Smoking |

|

|

0.000 |

0.006 |

|

Smoker/ex-smoker |

113 (87.6) |

66.5 |

|

|

|

Never smoked |

16 (12.4) |

90.8 |

|

|

|

Alcohol consumption |

|

|

0.005 |

0.880 |

|

Yes |

86 (66.7) |

69.7 |

|

|

|

No |

43 (33.3) |

81.0 |

|

|

|

Metastasis |

|

|

0.000 |

0.714 |

|

Yes |

18 (14.0) |

18.2 |

|

|

|

No |

111 (86.0) |

77.3 |

|

|

|

Infections |

|

|

0.247 |

-** |

|

Yes |

4 (3.1) |

55.6 |

|

|

|

No |

125 (96.9) |

75.0 |

|

|

|

Total |

129 (25.3) |

74.7 |

- |

- |

Captions: *SV Rate = Survival Rate. **(-) Not applicable.

Figure 1. Survival rate curves of statistically significant variables

Captions: A: Survival curve based on residence. B: Survival curve based on sex. C: Survival curve based on staging. D: Survival curve based on smoking. E: Survival curve based on physiotherapy treatment.

DISCUSSION

The survival analysis study helps to develop more effective therapeutic approaches in the oncological context by identifying variables that influence clinical outcomes in HNC10. This study found a notably high cumulative survival rate of 74.7%, with significant sociodemographic factors including sex and residence, and clinical factors as tumor staging, physiotherapy treatment, and smoking. This may be attributed to the fact that data were collected from a reference center for these neoplasms, where specialized treatment may have positively impacted the outcomes.

In a study conducted in Thailand analyzing 1,186 HNC cases, five-year survival rates for the overall cohort and specific subsites (oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx) were 24.1%, 25.9%, 19.2%, 13.4%, and 38.0%, respectively11.

Sex was shown to be an important prognostic factor for survival in patients with HNC. The survival rates for men and women were 65.8% and 84.4%, respectively. The data differs from the study by Lin, Hsu, Tsai12 which analyzed 2,753 participants in Taiwan with clinical and pathological characteristics of carcinoma with predominance of males (n = 2,451), only 122 women have been enrolled.

This difference may be related to distinct habits and lifestyles of exposure to the association between alcohol and tobacco. Studies confirm that smoking is more prevalent among men than women worldwide, particularly in developing countries, making tobacco a significant health and well-being threat. A large-scale cohort study in South Korea involving over 9.5 million individuals and conducted over ten years found that the incidence of head and neck cancer was significantly higher in men (0.19 per 1,000 person-years) than in women (0.06 per 1,000 person-years). The men in the study also smoked and consumed alcohol more frequently than women. Even after excluding individuals who had never smoked or consumed alcohol, the risk of head and neck cancer was still approximately 2.9 times higher in men. This suggests that additional biological or behavioral factors may contribute to this disparity2,12,13.

Patients living in the Metropolitan Region of Belém showed a survival rate of 66.5% and in the state’s inner cities, 79.4%. The study by Bigoni et al13. describes the evolution of cancer mortality in 133 intermediate Brazilian regions from 1996 to 2016, showing a high rate in the North region, especially in state’s inner cities and underserved areas, where poor transportation is an obstacle to reach other cities to seek treatment for complex diseases as cancer14. However, the low survival rate in metropolitan regions can also be attributed to behavioral and lifestyle factors, as excessive alcohol consumption, smoking, low fruit and vegetable intake and obesity. Improving health care and reducing socioeconomic inequalities can prevent increasing mortality trends by all cancers and specific cancers in Brazilian underserved regions15.

Disease staging, which takes into account tumor size, lymph node involvement and the presence of distant metastases, is an important prognostic factor for survival. The survival rate was 99.3% for patients with in situ disease, 90.7% for patients with local disease and 49.1% for patients with advanced disease.

An important finding in the review study by Andrés Coca-Pelaz et al15 was the correlation between tumor progression and stage. Therefore, a delay in the initiation of oncological treatment may have a direct impact on the prognosis and survival, especially in more advanced stages16.

Data analysis reveals that head and neck cancer patients who received physical therapy had a lower survival rate (16.7%) than those who did not (84.2%). This statistically significant difference is most likely due to physical therapy being indicated for patients in more advanced stages of the disease who have greater functional impairment and/or sequelae, and who are therefore eligible for physical therapy. HNC can have several functional effects on patients, affecting essential areas such as eating, breathing and communication. The main alterations include protection problems and trismus, which reduces mouth opening and hinders chewing and speech; facial paralysis, which compromises visual movement and expression; winged scapula, which impairs shoulder and arm mobility; and reduced range of motion in the upper limb, which compromises fundamental daily activities. These effects are related to both the tumor and surgical treatments, highlighting the importance of physical therapy monitoring to minimize sequelae and improve patients' quality of life17,18.

Smoking significantly influenced the survival outcomes of this population. It was observed that patients who were smokers or ex-smokers (66.5%) had a lower survival rate than those who had never smoked (90.8%). Of all the variables studied by Beynon et al.19, smoking was the strongest predictor of all-cause mortality in models adjusted for important prognostic factors, being one of the main causes of head and neck cancer. In the present study, alcohol consumption did not affect the survival of these patients.

In a study that followed 1,311 patients with HNC, it was observed that five-year survival was lower in patients who had a smoking history of more than 10 years/pack compared to non-smokers, and the authors also observed a strong association between HNC and abuse of alcoholic beverages20.

Sociodemographic and clinical variables are known to be associated with survival21. The level and mortality trend from oral and oropharyngeal cancer are influenced not only by exposure to risk factors, but also by sociodemographic and socioeconomic aspects and by the availability, effectiveness and quality of treatment offered to patients.

Environmental factors as prolonged smoking and low education are significantly associated with HNC. The results also showed a significant risk of head and neck cancer and breast cancer, potentially due to second-hand smoking or smoking habits in social environments that encourage smoking. Illiterate individuals have a higher risk of dying from HNC compared to those with a higher level of education, regardless of sex, due to greater exposure to risk factors and less access to health services which explains the observed inequalities22.

Although certain comorbidities are recognized as important factors contributing to reduced survival, these findings suggest that the presence of these conditions is secondary to clinical factors. Hashim et al. reported that comorbidity is common in patients with HNC and has a negative impact on survival23.

The study variables comorbidities, pathological fractures, infections and treatment were not significantly associated with survival, but the survival rate of patients with metastases was unfavorable (18.2%), while the survival rate of patients without metastases was 77.3%. Similarly, readmission showed an important association with survival of the patients investigated, an inverse association was found between hospitalization and survival, it is reported that patients requiring hospitalization are likely to have more complications, comorbidities and/or worse clinical conditions, and negatively impact the risk of death at the end of hospitalization24.

The present study did not identify palliative care as an independent factor influencing survival in patients with HNC. This may occur because this group often includes individuals with advanced disease stages and high clinical severity, for whom other prognostic variables have greater influence on survival outcomes25. Some studies report that patients receiving palliative care are more likely to die from HNC than others, with as 12-fold higher risk of early death observed in the palliative care group than in the curative group25,26.

This study was developed with secondary data, which may have affected the results. Among the study limitations, the lack of standardization of medical records, data recording and storage conditions may have contributed to sample losses due to illegibility of some data, although it did not exceed 15% of the medical records.

CONCLUSION

Because there has been no recent epidemiological analysis of this type of investigation in the scientific literature, the present study is relevant for the state of Pará. The authors concluded that the five-year overall survival rate for HNC patients was 74.7%, which is high compared to other Brazilian regions and developing countries.

Factors that significantly impacted survival among the patients were related to sociodemographic characteristics, as sex and origin, as well as clinical factors, as disease stage, physical therapy and smoking.

Further national studies should be conducted to identify the factors influencing population survival rate to help to develop strategies to combat HNC and guide screening and detection practices, and contributing to oncology care in local health systems. Understanding the population and clinical profile of patients undergoing HNC treatment is essential to develop public policies focused to prevention and early diagnosis strategies.

CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, writing and critical review. All the authors approved the final version to be published.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There is no conflict of interests to declare.

DECLARATION OF DATA AVAILABILITY

All content underlying the text of the article is contained in the manuscript.

FUNDING SOURCES

None.

REFERENCES

1. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Estimativa 2023: incidência de câncer no Brasil [Internet]. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2022 [access 2025 Apr 25]. Available at: https://www.inca.gov.br/sites/ufu.sti.inca.local/files//media/document//estimativa-2023.pdf

2. Gormley M, Creaney G, Schache A, et al. Reviewing the epidemiology of head and neck cancer: definitions, trends and risk factors. Br Dent J. 2022;233(9):780-6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-022-5166-x

3. Organização Mundial da Saúde. CID-10: Classificação Estatística Internacional de Doenças e problemas relacionados à saúde. São Paulo: Edusp; 2008.

4. Machado B, Barroso T, Godinho J. Impact of diagnostic and treatment delays on survival and treatment-related toxicities in portuguese patients with head and neck cancer. Cureus. 2024;16(1):e53039. doi: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.53039

5. Graboyes EM, Kompelli AR, Neskey DM, et al. Association of treatment delays with survival for patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(2):166-77. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2018.2716

6. Schlichting JA, Pagedar NA, Chioreso C, et al. Treatment trends in head and neck cancer: surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) patterns of care analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30(7):721-32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01185-z

7. SPSS®: Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) [Internet]. Versão 20.0. [Nova York]: International Business Machines Corporation; [sem data]. [acesso 2023 mar 9]. Disponível em: https://www.ibm.com/br-pt/spss?utm_content=SRCWW&p1=Search&p4=43700077515785492&p5=p&gclid=CjwKCAjwgZCoBhBnEiwAz35Rwiltb7s14pOSLocnooMOQh9qAL59IHVc9WP4ixhNTVMjenRp3-aEgxoCubsQAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds

8. Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Survival analysis: a self-learning text. 3. ed. New York: Springer; 2011. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6646-9

9. Conselho Nacional de Saúde (BR). Resolução n° 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. Aprova as diretrizes e normas regulamentadoras de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF. 2013 jun 13; Seção I:59.

10. Prakash Saxena PU, Unnikrishnan B, Rathi P, et al. Survival analysis of head and neck cancer: results from a hospital based cancer registry in southern karnataka. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2019;7(3):346-50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2018.08.007

11. Pruegsanusak K, Peeravut S, Leelamanit V, et al. Survival and prognostic factors of different sites of head and neck cancer: an analysis from Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(3):885-90. doi: https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.3.885

12. Lin NC, Hsu JT, Tsai KY. Difference between female and male patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma: a single-center retrospective study in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):1-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113978

13. Bigoni A, Ferreira Antunes JL, Weiderpass E, et al. Describing mortality trends for major cancer sites in 133 intermediate regions of Brazil and an ecological study of its causes. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):940. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6184-1

14. Im PK, Millwood IY, Guo Y, et al. Patterns and trends of alcohol consumption in rural and urban areas of China: findings from the China Kadoorie Biobank. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):217. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6502-1

15. Coca-Pelaz A, Takes RP, Hutcheson K, et al. Head and neck cancer: a review of the impact of treatment delay on outcome. Adv Ther. 2018;32:153-60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0663-7

16. Martos-Benítez FD, Soler-Morejón CD, Lara-Ponce KX, et al. Critically ill patients with cancer: a clinical perspective. World J Clin Oncol. 2020;11(10):809-35. doi: https://doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v11.i10.809

17. Jonsson M, Hurtig-Wennlöf A, Ahlsson A, et al. In-hospital physiotherapy improves physical activity level after lung cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Physiotherapy (United Kingdom). 2019;105(4):434-41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2018.11.001

18. Beynon RA, Lang S, Schimansky S, et al. Tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking at diagnosis of head and neck cancer and all-cause mortality: results from head and neck 5000, a prospective observational cohort of people with head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(5):1114-27. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31416

19. Du E, Mazul AL, Farquhar D, et al. Long-term survival in head and neck cancer: impact of site, stage, smoking, and human papillomavirus status. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(11):2506-13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.27807

20. Cunha AR, Prass TS, Hugo FN. Mortalidade por câncer bucal e de orofaringe no Brasil, de 2000 a 2013: tendências por estratos sociodemográficos. Ciência saúde coletiva. 2020;25(8):3075-86. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020258.31282018

21. Zhang X, Meng X, Chen Y, et al. The biology of aging and cancer: Frailty, inflammation, and immunity. Canc Journal. 2017;23(4)201-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/ppo.0000000000000270

22. Vučičević Boras V, Fučić A, Baranović S, et al. Environmental and behavioural head and neck cancer risk factors. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2019;27(2):106-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.21101/cejph.a5565

23. Hashim D, Genden E, Posner M, et al. Head and neck cancer prevention: from primary prevention to impact of clinicians on reducing burden. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(5):744-56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz084

24. Hembree TN, Thirlwell S, Reich RR, et al. Predicting survival in cancer patients with and without 30-day readmission of an unplanned hospitalization using a deficit accumulation approach. Cancer Med. 2019;8(15):6503-18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.2472

25. Talani C, Mäkitie A, Beran M, et al. Early mortality after diagnosis of cancer of the head and neck – a population-based nationwide study. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223154. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223154

Recebido em 4/5/2025

Aprovado em 16/7/2025

Scientific-editor: Anke Bergmann. Orcid iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1972-8777

![]()

Este é um artigo publicado em acesso aberto (Open Access) sob a licença Creative Commons Attribution, que permite uso, distribuição e reprodução em qualquer meio, sem restrições, desde que o trabalho original seja corretamente citado.